Insider’s Guide to Shintō Shrines

Shintō’s Sacred Forests and Japanese Environmentalism

Guideto Japan

Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

A sparkling river snakes through rice paddies surrounded by wooded hills in a verdant landscape dotted with farmhouses. At the foot of a prominent hillock or small mountain stands a torii gate marking the entrance to a Shintō shrine nestled among trees. This is the quintessential scenery of rural Japan, a harmonious landscape composed of fields, woodland, and running water that continues to evoke deep feelings of nostalgia among the Japanese—even though it is becoming increasingly difficult to find people who actually grew up in such an environment. It is the scenery of our spiritual home.

The mixed ecosystem surrounding the traditional Japanese rural community is referred to as satoyama. Although rich in flora and fauna, the woodland around these villages is not virgin forest but the product of many years of careful tending and stewardship by the local residents. The Japanese people have been planting and maintaining forestland since the Jōmon period. Today, primary or virgin forest constitutes only a small percentage of Japan’s total forestland. The “natural” environment familiar to the Japanese people was fashioned and maintained over the centuries by their forebears.

One key component of this traditional rural landscape is the Shintō shrine, most often situated in a sacred forest known as chinju no mori. From ancient times, a local Shintō shrine—dedicated either to an ujigami (the ancestral or tutelary kami of a particular clan) or an ubusunagami (the guardian kami of the locale itself)—constituted the focal point of each rural community, sustaining the rhythm of individual and communal life.

The basic principle underlying both the satoyama and the chinju no mori was reverence for and coexistence with nature. This ideal pervaded all aspects of Japanese culture. We see it in everything from garden design, which often imitates natural scenery or even incorporates the surrounding landscape as “borrowed scenery” (shakkei), to ordinary domestic architecture, with its papered shoji that can be opened to erase the boundary between indoors and outdoors and closed without shutting out the voice of the wind or the insects. To the Japanese, the sounds, scents, and even sensations (heat and cold) of nature in its varied manifestations were divine blessings. This reverence for nature is rooted in the indigenous concept of forests as sacred places inhabited or visited by the gods.

Ravages of Shrine Consolidation

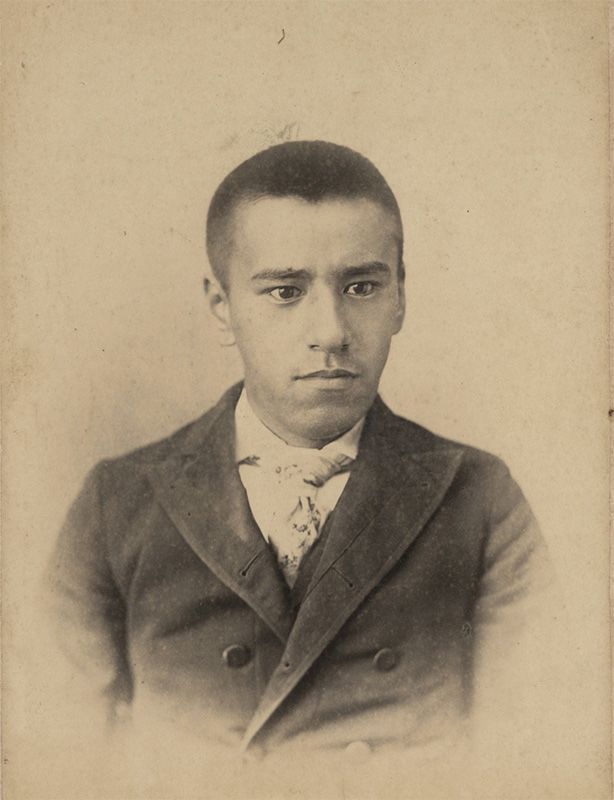

Minakata Kumagusu, the pioneering naturalist who opposed the systematic closure of small community shrines.

Minakata Kumagusu, the pioneering naturalist who opposed the systematic closure of small community shrines.

Up until the twentieth century, the chinju no mori was an integral part of the landscape in every corner of rural Japan. That began to change in the second half of the Meiji era (1868–1912), when the government embarked on a policy to ensure the viability of organized Shintō by consolidating the nation’s numerous shrines. As a result of a 1906 edict, small local facilities were forcibly merged into larger ones (jinja gōshi), reducing the total number of shrines from roughly 200,000 to about 120,000 nationwide. Certain areas of Japan were especially hard hit: Mie Prefecture lost about 90% of its shrines; in Wakayama Prefecture, the number fell from 3,700 to a mere 790. The grounds of the smaller shrines were sold off along with their chinju no mori, including ancient trees worshipped as himorogi. Under the 1906 edict, the land was surrendered to local governments without compensation, and countless local officials with their fingers in the till profited from the sale of the land and its timber.

The appalling onslaught continued until it ran into resistance spearheaded by naturalist Minakata Kumagusu (1867–1941). In his tract Jinja gōshi ni kansuru iken (Opinion on Shrine Mergers), Minakata argued passionately against the destruction of local shrines and their chinju no mori from the standpoint of their importance to human spiritual culture, local communities, and natural ecosystems. He went further, claiming that “love of one’s birthplace is the basis for love of country” and that the shrine merger program was “doing great damage to patriotic sentiment.” Opposition mounted, and the consolidation program lost momentum.

From Shrine Preservation to Environmentalism

Minakata was a native of Wakayama Prefecture, and one of his favorite spots for walking and collecting natural specimens was Cape Tenjinzaki in Tanabe. But Minakata worried even then that the area, with its spectacular scenery, would eventually be bought up by developers and turned into a resort, according to his daughter Fumie. In the 1970s, Tenjinzaki was rescued from just such a fate by the efforts of local citizens, who bought up the land to save it for posterity. This was the beginning of the national trust movement in Japan.

Tenjinzaki is located in the Kumano region, famous for the Shintō pilgrimage route that links the three shrines of Kumano Hongū (in Tanabe), Kumano Hayatama (Shingū), and Kumano Nachi (Nachikatsuura). These are shrines that preserve the original character of Shintō as nature worship. Their shintai—sacred objects inhabited by kami—are the local river, rock formation, and waterfall, respectively, and they are surrounded even today by lush, expansive chinju no mori. The unspoiled Shintō forests of Kumano nurtured the environmentalism of Minakata Kumagusu.

Kashima island in Tanabe bay is the site of a famous episode involving Minakata. In 1929, at the Emperor Shōwa's request, Minakata led the monarch (himself a biologist) on a nature walk there before reading him a lecture on slime molds and marine life. Minakata also presented the emperor with a gift of slime mold specimens in empty taffy boxes. The following year, the imperial visit was commemorated with a monument inscribed with a verse by Minakata: “Ocean breeze, blow gently and protect each twig of the forest that our emperor admired.” Kashima was designated a natural monument in 1935 and has managed to preserve its pristine environment as a result.

The island of Kashima, which the pioneering naturalist and conservationist Minakata Kumagusu introduced to Emperor Shōwa in 1929.

The island of Kashima, which the pioneering naturalist and conservationist Minakata Kumagusu introduced to Emperor Shōwa in 1929.

Visiting southern Wakayama again in May 1962, years after Minakata’s death, the emperor wrote the following poem: “I see Kashima rising dimly through the rain and think back on Minakata Kumagusu of Kii [Wakayama].”

The emperor’s poem is inscribed on a monument in front of the Minakata Kumagusu Museum in nearby Shirahama.

Saving Our Sacred Forests

One of the most outstanding examples of chinju no mori is situated right in the middle of Tokyo and dates back only to 1920. This is the forest of Meiji Shrine, dedicated to the spirit of Emperor Meiji and Empress Shōken. Construction of the shrine began in 1915, three years after the emperor’s death, and the forest in which it is located, covering some 70 hectares (170 acres), was created from scratch using trees donated from all over Japan and planted by an army of volunteers.

The forest surrounding Meiji Shrine in Tokyo.

The forest surrounding Meiji Shrine in Tokyo.

Elsewhere, however, Japan’s chinju no mori have not fared as well. Urban shrines in particular have suffered in the name of effective utilization of costly land, with the result that many are now virtually denuded. Sacred groves have been replaced with parking lots. Within the shrine grounds, trees have been cut down to make way for secular structures devoted to community activities and other purposes. Unfortunately, a “naked shrine” shorn of its sacred greenery does not inspire visitors with feelings of religious reverence. On the other hand, a forest by itself can inspire such sentiment, even without the help of Shintō structures. This, after all, is how our ancestors worshipped.

Over the past two centuries, modernization has taken its toll on the chinju no mori that nourished the Japanese reverence for nature. At the same time, the dedication of conservationists from Minakata Kumagusu on attests to the survival of that spirit. Meanwhile, the example of Meiji Shrine offers hope for the future. If it is possible to establish a rich forest ecosystem in the middle of Tokyo in a matter of decades, surely it is not so unrealistic to dream of the restoration of smaller chinju no mori in cities and towns around Japan.

(Originally published in Japanese on November 14, 2016. Banner photo: The sprawling evergreen forest around Meiji Shrine in Tokyo, planted when the shrine was established in 1920.)