New Perspectives on Miyazawa Kenji

Miyazawa Kenji: A Literary Life in Northern Japan

Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Religious Inspiration

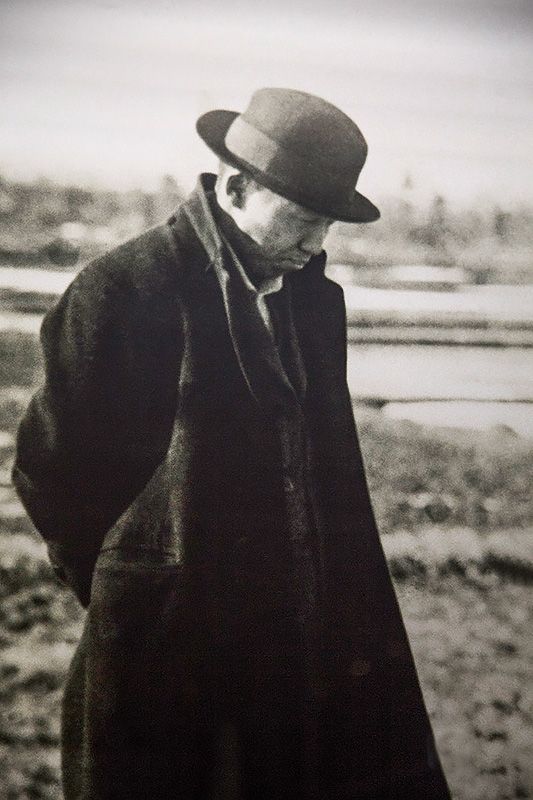

The poet and writer of children’s stories Miyazawa Kenji (1896–1933) secured his place in the annals of Japanese literature through the extraordinary worlds of his imagination. Born in 1896 to a family that ran a pawnbroking and used clothing business, he was raised in Hanamaki, Iwate Prefecture, in northern Japan. It was a harsh environment, presenting the constant threat of failed harvests and starvation.

In 1914, the year he graduated from school in Iwate’s capital of Morioka, Kenji read the Lotus Sutra and was passionately moved. The scripture became a lifelong cornerstone of his faith. In 1920, he joined Kokuchūkai, a Buddhist organization in the Nichiren school, which takes the Lotus Sutra as a central text. Inspired to seek a synthesis between religion and art, he persevered with creative endeavors. The Lotus Sutra is at the foundations of Kenji’s literary work, and he is regarded as a religious thinker as well as an author.

In 1921, he became a teacher at the prefectural agricultural school in Hanamaki. He began to write poems in the colloquial style, sending them along with children’s stories to local newspapers and amateur journals. In 1924, he self-published the poetry collection Haru to Shura (Spring and Asura) and the short story collection Chūmon no ōi ryōriten (The Restaurant of Many Orders).(*1)

Posthumous Masterpieces

In 1926, he left the agricultural school to become a farmer, forming a local association with other young farmers called the Rasuchijin Society. Kenji conducted lectures on agricultural science and arts, as well as encouraging music appreciation by playing records and holding instrument practice sessions. One of his main goals was to help farmers, such as by providing free instruction on the use of fertilizer; but he also longed to achieve a unification of agriculture, art, science, and religion. He faced increasing difficulties, however, as his activities drew the attention of the police authorities, and he fell ill with tuberculosis. After a temporary recovery, he started working for a rock-crushing company, but died of an onset of pneumonia in 1933 due to recurrence of his tuberculosis. Among the many unpublished masterpieces he left behind were the fantasy novel Ginga tetsudō no yoru (Night on the Galactic Railroad) and the now classic poem “Ame ni mo makezu” (“Undefeated by the Rain”).

Although highly praised by some poets, Kenji was virtually unknown at the time of his death. His poems and stories are infused with a vibrant linguistic sensibility, unfettered imagination, and sympathy with the natural world. Their acute observation of civilization steadily won more readers. Today he is one of Japan’s best-loved writers. His works form the basis for many popular contemporary picture books, plays, and films.

(Originally written in Japanese. Banner photo: A statue of Miyazawa Kenji in the garden of Iwate Prefectural Hanamaki Agricultural High School. © Ōhashi Hiroshi.)(*1) ^ Many of Miyazawa Kenji’s works have been translated into English several times, with different titles. Readers may know these works by other names.—Ed.