Saving Edo from War: The Political Insights of Yamaoka Tesshū

Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Yamaoka Tesshū (1836–88) was a retainer of the Tokugawa shogunate who played a vital role in assuring the peaceful handover of Edo Castle to imperial forces, headed by Saigō Takamori (1828–77), in the Meiji Restoration of 1868.

An accomplished swordsman, he later in life traded the study of martial arts for Zen. In 1883 he founded Zenshōan in Tokyo’s Yanaka district to honor those killed during Japan’s transition to a modern state.

(Clockwise from top): The front gate of Zenshōan; a commemorative tablet to Yamaoka Tesshū inscribed with a poem by Katsu Kaishū; the original pillar of the main gate engraved with the temple’s honorific name, Fumonzan.

(Clockwise from top): The front gate of Zenshōan; a commemorative tablet to Yamaoka Tesshū inscribed with a poem by Katsu Kaishū; the original pillar of the main gate engraved with the temple’s honorific name, Fumonzan.

A Bloodless Surrender

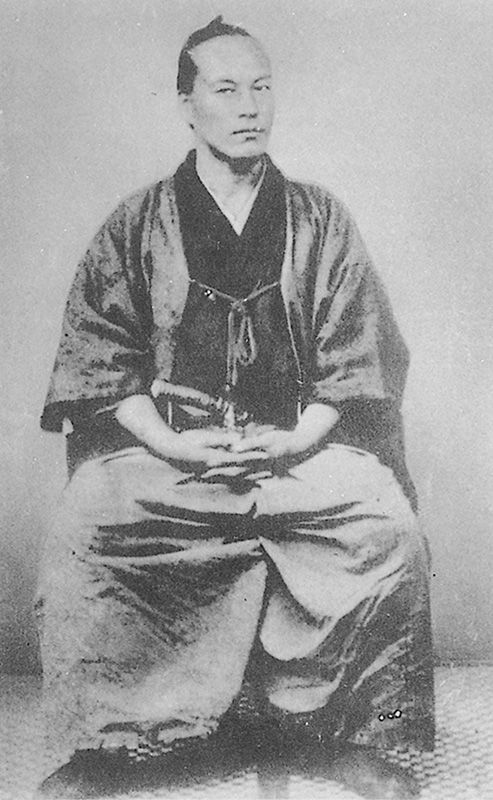

Yamaoka Tesshū around the end of the Edo period. (Courtesy of the National Diet Library)

Yamaoka Tesshū around the end of the Edo period. (Courtesy of the National Diet Library)

The Tokugawa shogunate was on the verge of collapse in January 1868, when pro-imperial forces led by the Chōshū and Satsuma domains faced off against samurai loyal to the feudal regime at the battle of Toba-Fushimi in the outskirts of Kyoto, sparking the Boshin War. The army of the newly established Meiji government quickly asserted its superiority, and by mid-March 50,000 soldiers stood ready to take Edo (now Tokyo), the seat of power of Shōgun Tokugawa Yoshinobu (1837–1913).

Katsu Kaishū (1823–99), who led the shogunal forces, knew a major battle in Edo would be devastating for the city and the nation. In hopes of avoiding such a conflict, he dispatched Yamaoka with a letter expressing Yoshinobu’s willingness to compromise. Yamaoka delivered the message to Saigō, who was encamped in Sunpu (now Shizuoka), on March 9 and boldly asked the general if he intended to attack Edo.

Saigō assured the envoy that his aim was not to thrust the nation into turmoil but to subdue those compatriots who were on a reckless path. Yamaoka responded that Yoshinobu was prepared to pay obeisance to the emperor and would, upon receiving him at the Buddhist temple Kan’ei-ji northeast of Edo Castle, be resigned to whatever fate the emperor decided, but warned that if Saigō were to rebuff this overture, he and 80,000 other Tokugawa loyalists were prepared to fight to their deaths to defend the honor of the regime. He again pleaded with Saigō to reconsider his plan to attack Edo and to avoid the needless deaths of the city’s residents. After leaving the room to consult with his advisors, Saigō told Yamaoka that he would forego the attack if Yoshinobu agreed to surrender under certain conditions.

This exchange laid the groundwork for a pivotal meeting between Katsu and Saigō on March 13 and 14 in Edo. The two men were aware that if fighting were to break out in the city, Britain, which was aligned with the Meiji forces, and Tokugawa-allied France might join the fray. In Japan’s fractured state, such a development could easily lead to colonization by the Western powers. On the eve of the planned attack, Saigō and Katsu reached an agreement for the peaceful handover of Edo Castle, saving residents of Edo from all-out war and assuring the survival of the nation.

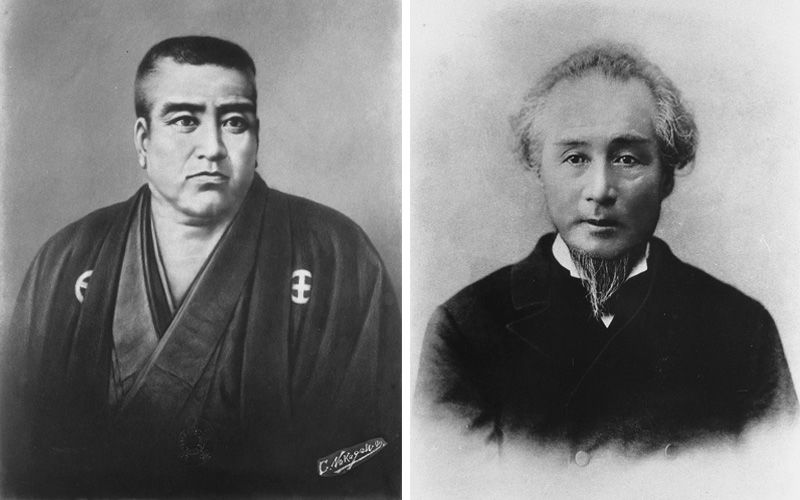

Saigō Takamori (left) and Katsu Kaishū. (Courtesy of the National Diet Library)

Saigō Takamori (left) and Katsu Kaishū. (Courtesy of the National Diet Library)

A Lifelong Centrist

Yamaoka went on to serve as Emperor Meiji’s chamberlain for 10 years and held various posts inside the Imperial Household Agency. He was conferred the title of viscount upon his retirement. (Courtesy of the National Diet Library)

Yamaoka went on to serve as Emperor Meiji’s chamberlain for 10 years and held various posts inside the Imperial Household Agency. He was conferred the title of viscount upon his retirement. (Courtesy of the National Diet Library)

As Japan marched toward militarism in the decades following the Meiji period, many hawks came to be revere Yamaoka as a true patriot. As a consequence, following the nation’s defeat in World War II, his legacy faded into the shadows as democratic ideas pushed nationalistic thought to the fringes of society.

But on closer examination, the far right’s affinity for Yamaoka can be said to be misplaced and does not accurately reflect his place in history. As I noted in the first part of this series, even influential Buddhist priest Yamamoto Genpō was labeled as a rightist for his association with onetime ultranationalist Yotsumoto Yoshitaka, despite also keeping council with well-known liberal figures.

Historians of Japan’s modernization have often characterized the era as one of conflict between progressive and conservative elements. But the political landscape leading up to and directly following the Meiji Restoration cannot be conveniently divided into the left and right. And as Yoshinobu’s surrender and the peaceful handover of Edo Castle illustrate, winning a larger victory for the nation often meant accepting a painful personal defeat.

This was an insight Yamaoka relied on in charting his life, and it undoubtedly came to serve his Zen practice and spiritual center of Zenshōan.

(Originally published in Japanese on February 10, 2017. All photos by Nippon.com except where otherwise noted.)