Manga and Anime in Japan Today

A Treasure Trove of Early Japanese Animation

Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

On February 22, 2017, the National Film Center at the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, released a website celebrating a century of Japanese animation. It makes available 64 short films produced between 1917 and 1941. English subtitles are provided, allowing unprecedented access to these pioneering anime works. Users can explore the films by category, choose from a chronological list, or pick a director’s work to dive into.

Rediscovered Early Works

The oldest film on the site is the 1917 Namakura-gatana (The Dull Sword), the earliest anime still in existence. Japan’s fledgling animation industry was hit hard by the Great Kantō Earthquake of 1923, which destroyed many of the first anime films. The Dull Sword was rediscovered in an antique market by an Osaka film historian in 2007 and expanded with additional footage in 2014.

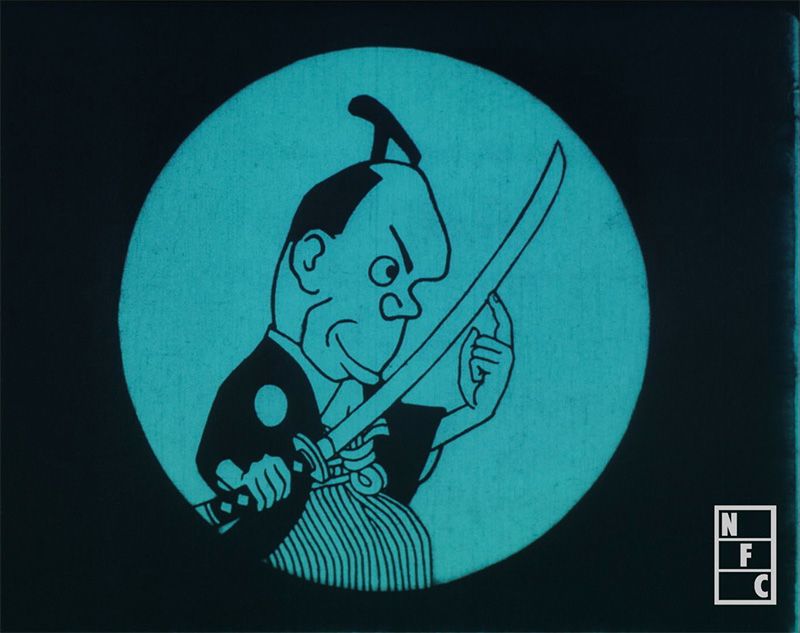

The four-minute film presents a grimacing samurai who buys a new sword and wants to test it out. There is a distinct sense of irreverence for the heroes of a former age, as his ambushes of innocent passers-by do not go according to plan. The animation is often unsophisticated, but there is a striking use of shadows in a late sequence.

Namakura-gatana (The Dull Sword; longest, digitally restored version, 1917).

Namakura-gatana (The Dull Sword; longest, digitally restored version, 1917).

The second-oldest film, Urashima Tarō (1918), was found at the same time as The Dull Sword and is the only other work on the site dated before 1924. At just over a minute long, it dashes through the plot of the classic Japanese fairy tale, often compared to “Rip Van Winkle.”

Dogs, Ducks, and War

Murata Yasuji (1896–1966) is the best represented animator on the site. His 23 films account for more than a third of the collection. These include works featuring Norakuro, a stray dog that becomes a soldier in a canine army. The character originated in manga and rose to fame during the 1930s, when Japan was at war with China. The series shifted over time from comedy to propaganda.

Norakuro gochō (Corporal Norakuro, 1934).

Norakuro gochō (Corporal Norakuro, 1934).

This change can be seen in miniature in the three films on the site. In the first two, released in 1933, Private Norakuro begins as a bumbling, comic character. By the third film, Norakuro gochō (Corporal Norakuro, 1934), the dog is much more heroic, as he foils an enemy plot. For a less politically charged Murata menagerie, try his 1928 film Dōbutsu Orinpikku taikai (The Animal Olympics).

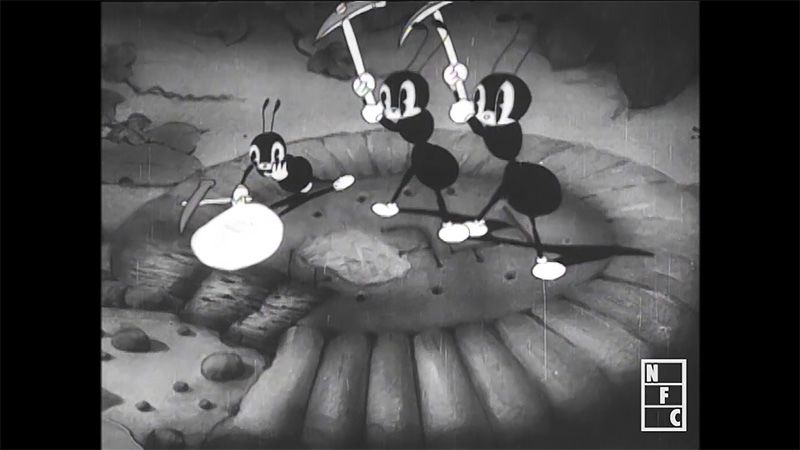

Seo Mitsuyo (1911–2010) displays Disney influences in Arichan (Arichan the Ant, 1941). The titular young ant steals a violin and joins other insects for several beautifully animated musical adventures. These include a memorable encounter with a terrifying human child. In the traditional spirit of wholesome family entertainment, Arichan learns a lesson along the way.

Arichan (Arichan the Ant, 1941).

Arichan (Arichan the Ant, 1941).

In a more military vein, there is Ahiru rikusentai (The Quack Infantry Troop, 1940). This depicts a battle between ducks and frogs, but takes a pacifist turn. Seo is remembered particularly for a 1944 propaganda film—Momotarō: Umi no shinpei (Momotarō’s Divine Sea Warriors), at 74 minutes in length, Japan’s first feature-length animation—but this is not available here.

One of the site highlights is Ponsuke no haru (Spring Comes to Ponsuke, 1934) by Ōishi Ikuo (1902–44). It starts off cute with a young tanuki (often called a raccoon-dog) digging a hole in the snow in search of bamboo shoots to eat. But it also has its grotesque side, including bizarre moving masks on display on the wall of the tanuki home. Everything resolves in a surreal but charming dance to welcome the spring.

Ponsuke no haru (Spring Comes to Ponsuke, 1934).

Ponsuke no haru (Spring Comes to Ponsuke, 1934).

Anime has become one of Japan’s most celebrated exports, shaping the image of the country around the world. The early films made available on the site demonstrate the creativity of pioneering artists getting to grips with a new medium.

All footage and photographs courtesy of the National Film Center at the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo. Portions of original material provided by Matsumoto Natsuki for Namakura-gatana (The Dull Sword; longest, digitally restored version). Original material provided by Planet Film Archive for Ponsuke no haru (Spring Comes to Ponsuke).

(Originally written in English by Richard Medhurst of Nippon.com. Banner photo: Tanuki and bamboo shoots dance together in a scene from Ponsuke no haru.)