Furiously Becoming a Lion

Society Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

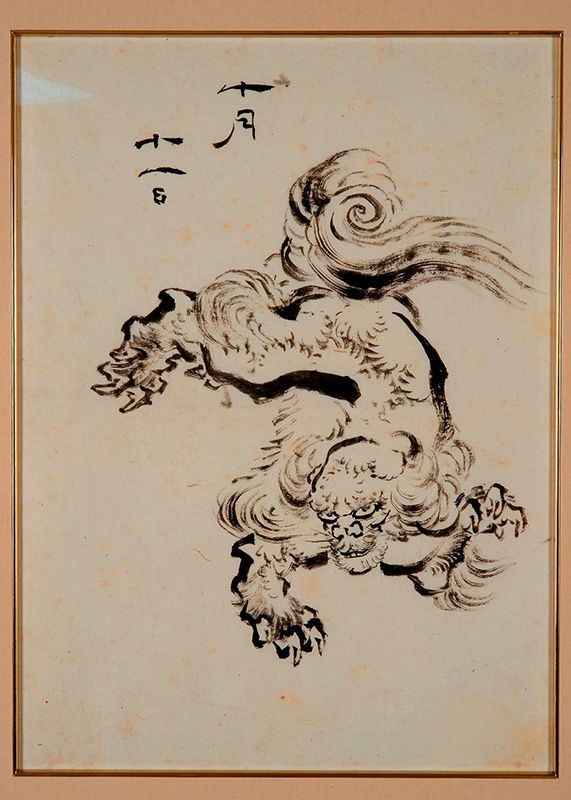

Did the Japanese people in the Edo period (1603–1868) ever see an actual lion? The celebrated artist Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849) of “The Great Wave off Kanagawa” fame made it a routine in his later years to draw a lion each day, but the pictures he drew don’t exactly resemble the lions that we know.

A Hokusai drawing of a lion from his Nisshin joma (A Daily Charm Against Evil) series. (From the collection of the Hokusaikan Foundation.)

A Hokusai drawing of a lion from his Nisshin joma (A Daily Charm Against Evil) series. (From the collection of the Hokusaikan Foundation.)

The imagery of the lion arrived in Japan via the Silk Road in a form with the animal usually depicted together with the peony flower; the connection is apparently derived from Buddhist scripture.(*1) When that image is transposed onto the kabuki stage, the lion dances gloriously, swaying and swirling his magnificent shaggy mane of white or red.

The lions of kabuki are proud, valiant creatures, whose fierce and noble spirits for some reason have a habit of entering and possessing human beings. In the dance play Hanabusa shūchaku-jishi (The Blossom-Coated Lion), a lion spirit possesses a beautiful courtesan. And in the classic Renjishi (Father and Son Lions)—although this was first performed five years after the Edo period ended—the spirit slips into two kyōgen actors. The dance is based on the folk tale about the father lion pushing his cubs over a precipice to rear only the ones strong enough to run back up the cliff.

The Child Lion Heir to a Late Father

The dance play Renjishi went on stage at the Shinbashi Enbujō theatre this past January, with Nakamura Kichiemon II(*2)playing the lead. In my previous article I was rather coy about “my favourite actor,” only hinting at his identity. Well, this is him: Kichiemon. Kabuki actors all have a yagō, a sort of nickname for their clan, and his is Harimaya. He was recognised as one of Japan’s living national treasures last summer. For fans of jidaigeki, Japan's period dramas set in the Edo period, he is instantly recognisable as Hasegawa Heizō, hero of the crime drama series Onihei hankachō (Onihei’s Book of Judgments). In kabuki, he is best when playing the great dramatic roles of great depth and scope, like Benkei in Kanjinchō (The Subscription List) or Ōboshi Yuranosuke, the fictional version of the historical Ōishi Kuranosuke, leader of the 47 samurai dramatised in the kabuki play Kanadehon Chūshingura (The Treasury of Loyal Retainers). If not in kabuki, he is the kind of actor one would dearly love to see play the likes of Othello, Macbeth, and King Lear.

He is best when inhabiting those great roles with their grand, eloquent speeches. This means that ever since I became a big fan, he has rarely been in a dance play. Moreover, he has no son or heir who would ordinarily be his partner in the dance as the lion cub. So I had always sort of assumed I would probably never see Harimaya do the keburi, the lion swishing his mane round and round.

The keburi, or the mane-swishing, is one of the showcase pieces in kabuki. The idea is not for the actor to go over the top and spin his head willy-nilly. He must keep his entire body in control and gyrate precisely, spinning his upper body, swishing the heavy mane-wig to embody the noble lion in throes of exquisite frenzy. And since kabuki performances usually run for at least 25 days, the actor must maintain his health and stamina for that duration. In short, it's hard work.

This was all the more reason for me to go agape and issue unintelligible sounds when I first learned that Harimaya was going to perform Renjishi, and that the lion cub would be played by Nakamura Takanosuke. The 12-year-old boy is the heir to the master dancer and virtuoso actor Nakamura Tomijūrō V,(*3)who passed away last year. The boy Takanosuke is now without a father. Kichiemon has no son or heir. And the two paired up to perform Renjishi in honour of the master thespian and dancer Tomijūrō.

Kabuki is an art form that has lasted for hundreds of years because the members of each generation of artists devote themselves to passing their art, craft, and passion on to the next generation. It is only because the artists through the ages committed themselves to the continuation of the art and heart of kabuki that we can idly wonder if people of the Edo period had ever seen an actual lion as we sit and watch Renjishi.

Soft and Light the Actor

As for the actual performance, especially on the final day, Takanosuke was brimming over with the exuberance of youth. He was like a ball or a balloon, all pumped up, bouncy, on the verge of bursting. And then there was Kichiemon. He danced in the first half as the kyōgen actor Ukon. Oh, the delicacy! In contrast to the young Takanosuke, whose every move was quick and sharp, the virtuoso actor moved in well-rounded, rich, and mature motions. Supple and delicate. As he moved, he also moved the air about him, and that air was deliciously soft and warm; it was like being wrapped in a huge, sumptuous goose-down comforter.

But once the spirit of the father lion enters into Ukon, he turns on the kyōgen actor Sakon (played by Takanosuke), who in turn becomes a lion cub. The father lion kicks the cub down into the abyss to test his resilience. At this point it is no longer clear whether they are man or beast. Nor is it clear whether the father lion is grieved or grimly determined. Either way, the air has become thick with emotion, and so the sunlit joy of what follows is all the brighter. The cub starts to climb back up the cliff, and seeing this, Kichiemon’s whole demeanour is lifted up. His expression of joy is as if a sudden slant of light shines through the clouds. The father lion beams. When I was there, there was a collective intake of breath among the audience.

Two Lion Whirlpools

And then there is the keburi. The spirit of the father lion comes back onto the stage wearing a magnificent white mane, the lion cub in a similar red mane. The two actors had been doing this for the past 24 days straight; there was no question they were exhausted. But still, the lion cub started to rotate straight away, his whole body crying, “I just can’t help it!” It was as if he couldn’t contain the movement that whirled around within him. He whirled and whirled. Spinning and spinning. Powerfully, as if he was about to burst.

And then there was Kichiemon, the father lion. Just before he started to spin his mane, he bent forward and let the mane sway ever so slightly right to left. It was as if his body and mane were shaking, quivering, writhing—as if something untamed and tumultuous sought to erupt forth from the depths of his being. I was totally blown away by this.

There was no way he wasn’t tired. Kichiemon is not a 12-year-old boy. But he was being propelled by something bursting from the inner depths of his actor-being. Quivering with barely-controlled momentum. And after shaking like that for a moment that seemed like en eternity, he snapped his body up straight, on cue. He raised his head and there, beneath his mane, his face became visible. Fierce intensity was written on his face. Here was an actor so accomplished, so acclaimed that he had earned the title “national treasure.” And yet, he was desperately battling his way towards the final keburi like any rising star.

And then he rolled. Spun. Rotating his entire body. He whirled his mane, his body—and, along with it, the very space of the stage itself. The air spun round and round like in a gigantic centrifuge. The whole space within the theatre itself was spinning with the actor as its centre. Round and round. Full of power, intensity. Building up to a frenzy, yet staying exquisitely calm and controlled.

How could I not be moved?

Besides, this might have been the last time we’ll see Kichiemon’s keburi. His performance made me grateful that I am his fan. It was that kind of experience. (March 1, 2012)

(Originally written in Japanese. Translated into English by the author.)

(*1) ^ The idiom shishi shinchū no mushi (an insect within the body of the lion) is often used to mean something malignant within a group or organisation. The original phrase is said to derive from Buddhist scripture referring to a parasitic infestation that kills a lion from within. The analogy is to a person who, despite being a believer, does damage to the faith of Buddha from within. According to the parable, the insect is susceptible to dewdrops from the peony flower, and so the lion is often seen near the flower. Hence, the combination of the lion and the peony is frequently depicted on byōbu (folding screens) and fusuma (sliding doors).

(*2) ^ Born in 1944 as the second son of Matsumoto Kōshirō VIII (later Matsumoto Hakuō I). He became the adopted son of his maternal grandfather, Nakamura Kichiemon I, and made his stage debut at four years of age. He inherited his grandfather’s stage name and became Nakamura Kichiemon II at 22.

(*3) ^ Born in 1929 as the eldest son of Nakamura Tomijūrō IV. Made his stage debut in 1943 at the Nakaza in Osaka. Was recognised as a living national treasure in 1994.

Kato Yuko kabuki performing arts culture lion dance kyōgen Renjishi Nakamura Kichiemon Takanosuke Tomijūrō