Solving the Riddle of Slumber: Cutting-Edge Research Hub in Tsukuba Focuses on Sleep

Science Technology Lifestyle- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

International Hub for Sleep Research

“That deplorable curtailment of the joy of life,” the author Virginia Woolf called it. Like it or not, we spend one-third of our lives in the unproductive and vulnerable state of sleep. This is true not just for mammals; virtually all creatures on earth, right down to flies and roundworms, live in a perpetual cycle of sleep and wakefulness. It is said that anyone who finally solves the mystery of why we sleep, of what the essence of slumber is, deserves a Nobel Prize.

The International Institute for Integrative Sleep Medicine, led by Professor Yanagisawa Masashi of the University of Tsukuba, is intent on uncovering that elusive secret. A research center focused on the basic science of sleep that has gathered about 200 researchers from Japan and abroad, IIIS was selected in 2012 for inclusion in the World Premier International Research Center Initiative of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology. Under the program, it will receive annual research funds of roughly ¥600 million over the course of 10 years.

There are numerous sleep disorders that require urgent medical attention, including sleep apnea syndrome. While many clinical sleep centers treat these conditions and conduct research on their treatment, basic research is equally indispensable. IIIS is a rare research institute with the mission of shedding light on the mechanism and function of sleep.

A Brief History of Sleep Medication

Yanagisawa became deeply committed to sleep research after discovering orexin (also known as hypocretin), a substance that promotes wakefulness, in a 1998 research study on the switching between sleep and wakefulness.

The Role of Orexin in Sleep-Wake Regulation

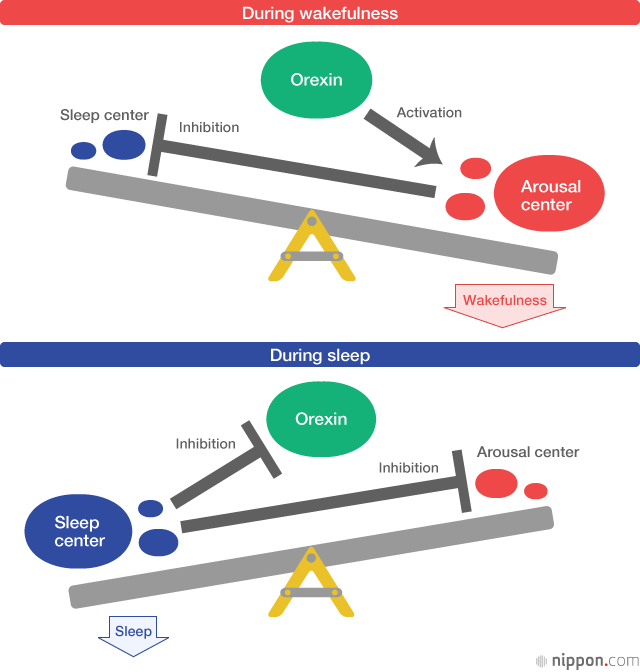

During wakefulness, orexin keeps the arousal switch in the “on” position by activating the brain’s arousal system, and the arousal center suppresses the sleep center. During sleep, the sleep center is active, and orexin-producing cells and the arousal center are both suppressed.

During wakefulness, orexin keeps the arousal switch in the “on” position by activating the brain’s arousal system, and the arousal center suppresses the sleep center. During sleep, the sleep center is active, and orexin-producing cells and the arousal center are both suppressed.

Orexin is a neurotransmitter in the brain, where it exerts its arousal effect by binding with proteins known as orexin receptors. When substances structurally resembling orexin are administered, they bind with the orexin receptors instead, shutting out orexin and allowing the body to maintain sleep. Merck and Co. of the United States harnessed this mechanism to develop a sleep aid (orexin receptor antagonist) under the trade name Belsomra, also known as suvorexant. The drug went on sale in Japan in 2014, ahead of other countries.

The world is home to many people suffering from insomnia. Barbiturates—drugs derived from barbituric acid that first appeared in the early twentieth century—were once commonly used to treat this condition. But these drugs are so powerful that they can inhibit breathing when taken in high doses. For this reason, they were frequently used in suicides. From the mid-twentieth century onward, benzodiazepines and, later, nonbenzodiazepines have replaced barbiturates as safer alternatives.

Professor Yanagisawa Masashi of the University of Tsukuba.

Professor Yanagisawa Masashi of the University of Tsukuba.

All three groups of drugs fundamentally work in the same way: They reduce stimulation in the brain by activating a type of neurotransmitter called gamma-aminobutyric acid, or GABA. They put subjects into a forced state of sleep, the quality of which is a far cry from that of naturally induced sleep. Giving up these drugs cold turkey cause withdrawal symptoms. Moreover, prolonged use could lead to tolerance, requiring greater dosages to achieve the desired effect, as well as a variety of serious side effects including flaccid muscles, lightheadedness, and falls.

Decades passed without the appearance of a better means of inducing sleep. In 2010 a new sleep aid was introduced that mimics melatonin, the hormone that regulates the body’s circadian clock. But this drug does not have an immediate effect, as it takes time for it to restore the proper rhythm of sleep.

Developing a New Class of Sleep Aids

As a graduate student at the University of Tsukuba, Yanagisawa discovered a potent vasoconstriction agent called endothelin. This brought him to the attention of Joseph L. Goldstein and Michael S. Brown of the University of Texas, who jointly won a Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their studies regarding cholesterol. At their invitation, Yanagisawa moved to the United States in 1991 and took a position at their school. Sakurai Takeshi (now a professor at Kanazawa University) followed him to Texas, where together they made the groundbreaking discovery of orexin.

The function of the newly identified substance was initially unknown. It was given the name “orexin” from the Greek word orexis, meaning “appetite,” because the cells that produce it are located in the hypothalamus, a part of the brain associated with regulating appetite and weight. When genetically modified mice were produced that do not manufacture orexin, however, they ate only slightly less than regular mice.

Observing their behavior, the researchers found that the mice would abruptly cease activity and collapse, only to get up several minutes later. Both their abnormal behavior and their brain wave patterns were consistent with narcolepsy, a form of hypersomnia (excessive daytime sleepiness). It was later confirmed that human narcolepsy patients also exhibited a shortage of orexin.

At first, businesses worldwide sought to draw on the appetite-controlling effect of orexin to develop weight loss drugs. But once the neurotransmitter’s role in sleep regulation was played up, they all shifted their focus to developing sleep medication. Yanagisawa, on the other hand, was opposed to making sleep aids based on substances that inhibit the action of orexin, known as orexin receptor antagonists. The risk of triggering narcoleptic symptoms made them too dangerous to be used in drugs, he believed.

Merck, meanwhile, moved quickly. The company administered large doses of candidate substances to mice to verify that they do not cause narcolepsy and came out with an orexin-targeting sleep aid that induces more natural sleep than its predecessors. Belsomra, whose name is based on the French word belle (“beautiful”) and the Latin suffix -somnia (signifying sleep), debuted on the US market in March 2015 and has been approved in seven countries. It is expected to fetch annual sales exceeding $500 million (¥60 billion).

Conversely, activating the effect of orexin rather than suppressing it would make it possible to maintain a waking state. IIIS is working to develop such a drug—an orexin receptor agonist—to treat narcolepsy, a condition in which patients experience overwhelming daytime drowsiness to the point where it interferes with their daily life. It is said to affect roughly 1 in 600 Japanese, but there is no definitive cure. Although the market for narcolepsy therapeutics is small, a drug that increases orexin activity could remedy heavy eyelids brought on by a variety of other causes, such as jetlag, depression, Alzheimer’s disease, and drug side effects. The prospective drug has already been shown to be effective in animals.

Tracking Down the Genes Related to Sleep Abnormalities

University-led drug discovery, aimed at commercial application, constitutes only a fraction of the research conducted at IIIS.

Three major factors are involved in regulating sleep. The first is the circadian rhythm. The human brain has an internal clock with a cycle of roughly 24 hours, synchronized with the earth’s rotation. The second is a homeostatic mechanism that makes one feel sleepy when fatigue accumulates in the brain after hours of staying awake. Finally, emotion also plays a role; falling asleep is much more difficult when one is emotionally charged.

Scientific research entails a process of first coming up with a hypothesis, then testing it. The black box of sleep is so substantial, however, that forming a meaningful hypothesis is difficult; the phenomena of sleep and wakefulness can be observed, but not what is taking place inside the brain during these states. IIIS therefore set out to pinpoint the genes linked to sleep-wake regulation by studying the phenomena.

Administering a chemical substance that induces mutations results in mice with randomly damaged DNA. Breeding about 10,000 of these mice and measuring their brain waves yields a small number of specimens that exhibit abnormal sleep-wake patterns. If the anomaly is caused by defective genes, it will be passed on to the next generation. The institute has thus far succeeded in identifying genetic mutations responsible for creating strains of mice that sleep for exceedingly long stretches and those that have very short REM sleep episodes. These genes may eventually be targeted for the treatment of sleep-related diseases.

Endothelin, the vasoconstriction agent that Yanagisawa first discovered, has also been targeted to develop a drug: Bosentan, which is used to treat a serious illness called pulmonary hypertension.

As a medical doctor, Yanagisawa is less dedicated to pure science than to the end goal of benefiting patients through his research. But he aspires to conduct “work that gets to the core of sleep,” saying, “Focusing on therapy as the only goal would cloud our field of vision.” His work is gradually making progress, as evidenced by a paper published in March 2015 by a joint research team comprising members of IIIS, including Yanagisawa, and the University of Texas, demonstrating the existence of pacemaker cells in the brains of mice that regulate the circadian clock.

In June 2015 the IIIS facility was enhanced with the completion of an 8,000-square-meter research building. Drawing on years of experience living in the United States, Yanagisawa incorporates elements of American organizational culture at the institute. He keeps the number of researchers fluid, as well as the use of space, so that they can be adjusted according to the progress in each research theme.

In the words of Voltaire, “Providence has given us hope and sleep as a compensation for the many cares of life.” May that hope—as well as that healthy sleep—be plenty.

(Originally published in Japanese on August 5, 2015.)Sleep University of Tsukuba Yanagisawa Masashi orexin hypocretin narcolepsy Belsomra suvorexant