The Secret Alliance with Japan Shattered by the Russian Revolution

Politics- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

A Diplomatic High Point

The words “100 years” have an almost magical power in Russian. The desire to live to 100 is perceived as a wish for eternal life. This may be because—unlike the Japanese—Russians rarely live so long.

A centennial is the most significant of anniversaries. People are interested in what happened 100 years ago, even if it is a relatively trivial event. The Russo-Japanese pact of 1916, however, was far from trivial.

On July 3, 1916, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Sazonov and Japanese Ambassador Motono Ichirō signed a treaty in Petrograd (today Saint Petersburg) concluding a military and political alliance. This marked the all-time high point of the two countries’ relations. The following year, the Russian Revolution rendered the alliance void, burying its potential for cooperation at a scale historians can only guess at. But rather than speculating, let us consider the historical facts.

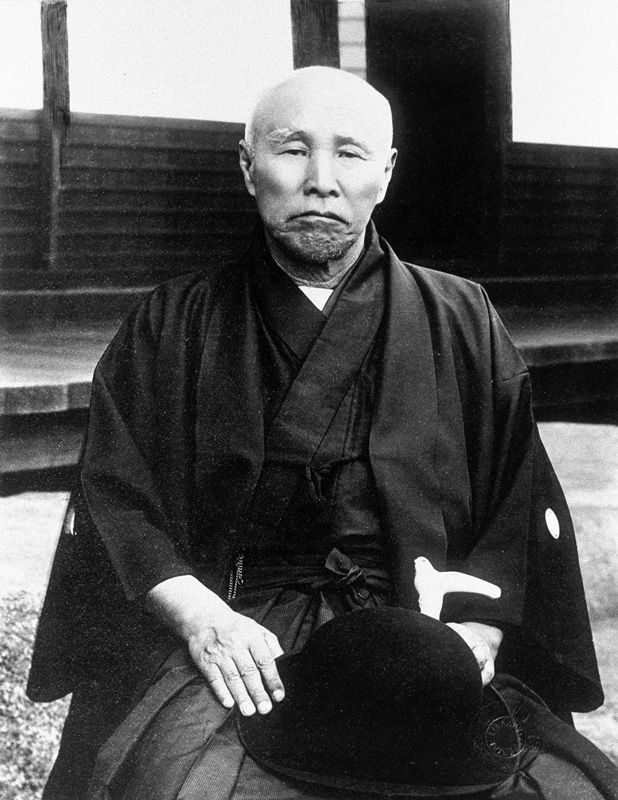

Field Marshal Yamagata Aritomo (1838–1922). Born to a low-ranking samurai family in the Chōshū domain, he became a central figure in the Meiji Restoration of 1868 and one of Japan's first prime ministers.

Field Marshal Yamagata Aritomo (1838–1922). Born to a low-ranking samurai family in the Chōshū domain, he became a central figure in the Meiji Restoration of 1868 and one of Japan's first prime ministers.

From the beginning of 1915, Japanese newspapers had been talking about the need for an alliance with Russia. Both nations were fighting against Germany and the Central Powers in the early stages of World War I. Nikolai Malevsky-Malevich, the Russian ambassador to Japan, wrote to Foreign Minister Sazonov that since the outbreak of the war, voices in the Japanese media debating an alliance had become so commonplace that there was hardly a newspaper or periodical that had not discussed it. He added that the idea had already proved popular among the general public.

At the heart of the debate was the question of what it would mean to be in an alliance. For most, this implied that both countries would be obliged to provide military assistance to the other in the case of conflict with a third party, as in the Anglo-Japanese Alliance of the time. Was such a treaty with Russia necessary?

“Imperial Diplomacy” as a Key to Alliance

Ōkuma Shigenobu (1838–1922). Born in the domain of Saga, he served as prime minister of Japan and founded Waseda University.

Ōkuma Shigenobu (1838–1922). Born in the domain of Saga, he served as prime minister of Japan and founded Waseda University.

In February 1915, Field Marshal Yamagata Aritomo, a former prime minister, submitted a memorandum to the Japanese government. He was skeptical about the chances for victory of the Allied Powers and believed that the war would end in a stalemate. This would disrupt the global balance of power, leading to heightened tensions in Asia, where he believed the United States would join the fight. In addition to the existing agreement with Britain, Yamagata proposed to form an alliance with Russia that would obligate the nations to render military support and protect the territorial integrity of China—the implication was, from countries that were not part of the alliance.

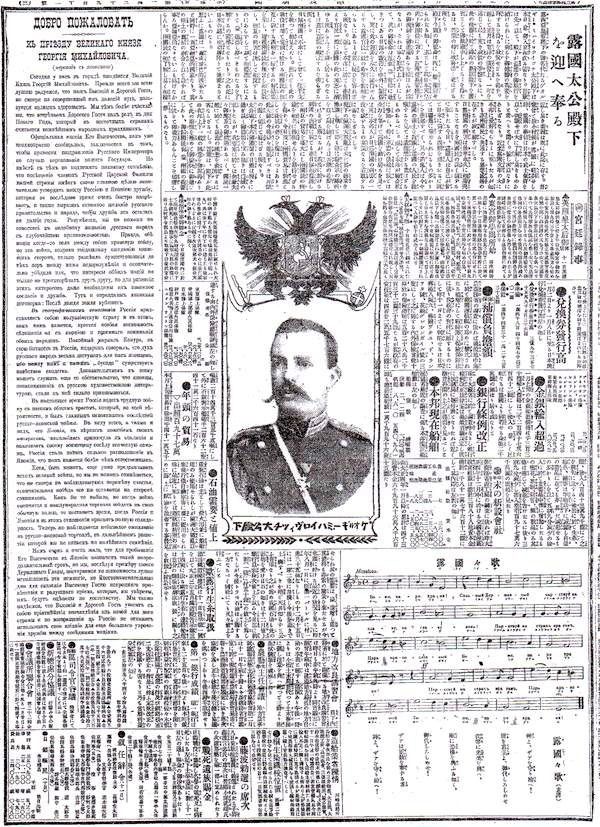

A report on the visit of Grand Duke Mikhailovich in the January 12, 1916, Yomiuri Shimbun.

A report on the visit of Grand Duke Mikhailovich in the January 12, 1916, Yomiuri Shimbun.

Prime Minister Ōkuma Shigenobu’s cabinet rejected the proposal, so Yamagata decided to enlist the support of Emperor Taishō. The quickest route to success, as he saw it, was to have a member of the Russian imperial house visit Tokyo. Later in 1915, Major General Nakajima Masatake, who was assigned as an observer to the general headquarters of the Russian army, casually remarked in conversation with the czar’s surgeon, Sergei Fedorov: “If the czar sent a grand duke to Japan, it would undoubtedly make a wonderful impression, and Japan would intensify its efforts to help Russia in its struggle against Germany.”

Japanese Ambassador to Russia Motono Ichirō (1862–1918). After 10 years of service in Russia, he was awarded the title of viscount and then appointed as foreign minister.

Japanese Ambassador to Russia Motono Ichirō (1862–1918). After 10 years of service in Russia, he was awarded the title of viscount and then appointed as foreign minister.

This wish was conveyed to Czar Nicholas II, who the very next day entrusted this mission to Grand Duke George Mikhailovich. The ostensible purpose of the visit was to congratulate Emperor Taishō on the completion of his formal enthronement ceremonies in November 1915. When the grand duke arrived in Tokyo in January 1916, the emperor himself met him at the station.

After negotiations by individual diplomats came to an impasse, Yamagata demanded that Foreign Minister Ishii Kikujirō reach a general agreement with Russia. He insisted that maintenance of peace and security in East Asia was only possible through cooperation between the two empires. Ishii and Ōkuma did not particularly want an alliance with the continental giant, but Yamagata doggedly imposed his will.

Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Sazonov (1860–1927).

Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Sazonov (1860–1927).

Many earlier historians believed that Ambassador Motono had drawn up the treaty for the 1916 alliance. The documents, however, show the role of Yamagata in paving the way with his great diplomatic skills and geopolitical thinking. A key element of his strategy was “imperial diplomacy.” After the visit of the grand duke as an emissary of Czar Nicholas II, and his welcome by Emperor Taishō, there was no room for open objections. The rest was a matter of simple procedure.

On February 18, 1916, Motono handed Sazonov a note suggesting that official negotiations be opened. Taking into account Russia’s weakness in the Far East, Nicholas II recognized the usefulness of the alliance with Japan. The treaty was a new stage in the countries’ relations, just a decade after the close of the Russo-Japanese War (1904–5). It is therefore wrong to see it as a sign that Russia was giving up its hopes of influence in the region.

Secretive and Short-Lived

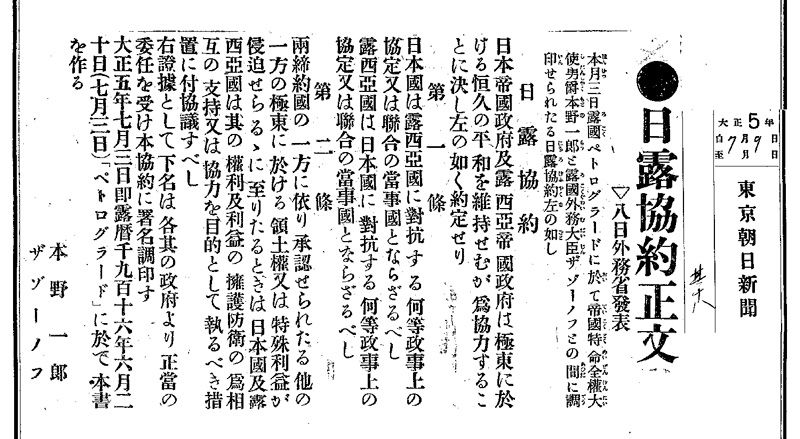

The official text of the agreement between Japan and Russia in the newspaper Tokyo Asahi Shimbun on July 9, 1916.

The official text of the agreement between Japan and Russia in the newspaper Tokyo Asahi Shimbun on July 9, 1916.

The published articles of the treaty included the obligations of both parties not to enter into any agreements or pacts against each other. They also set forth the arrangement to cooperate in defending mutually recognized territorial rights and special interests in the Far East.

At the same time, “to deepen the ties of friendship between the two countries,” they concluded a secret agreement. In this, they stated that they would protect China from political dominance by any third power that harbored hostile intentions against Russia or Japan. If measures taken led to war with a third country, then the other party would have to come to the aid of its ally when requested. The parties were not allowed to conclude peace with a common enemy without mutual consent. Finally, they guaranteed that support would be in proportion to the scale of the conflict.

Japan and Russia agreed to an alliance of five years, which was to remain the deepest secret. Of Russia’s ministers, only Prime Minister Boris Stürmer knew of its existence. However, this lasted no longer than the following year. When the Bolsheviks seized power in November 1917, they declared an end to secret treaties. They caused considerable confusion and embarrassment by publishing many documents relating to secret treaties between the Russian Empire and the other Allied Powers. The Russo-Japanese alliance became a thing of the past before it had the chance to come to fruition.Photo credits:

- Yamagata Aritomo: Kinsei meishi shashin (Photographs of Modern Figures), National Diet Library, Japan

- Ōkuma Shigenobu: Kinsei meishi shashin (Photographs of Modern Figures), National Diet Library, Japan

- Motono Ichirō: United States Library of Congress Prints and Photographs division

- Sergei Sazonov: Project Gutenberg