Once a Trendsetter, Harajuku Is Suffering a Fading Sense of Identity

Lifestyle Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Last Days for Landmark Station Building

Harajuku today bustles with domestic and international visitors, the crowds as lively as if they were at a festival. Like Asakusa or Shibuya, the trendsetting district is one of Tokyo’s top tourist spots, with people flocking to take in its youth culture and cutting-edge fashion. Standing out amid the modish surroundings is Harajuku Station. A popular backdrop for Instagram shutterbugs, the landmark lends a nostalgic charm to the area’s vibrant atmosphere.

Completed in 1924, the JR Harajuku Station is the oldest wooden train station in the metropolis. The two-story structure sports a gable roof lined with bluish-gray copper sheets and a central tower rising upward like a belfry, while the half-timbered walls set dark wooden beams against a white background. Flanked by the greenery of Meiji Shrine, it has the appearance of a venerable German or British building.

Harajuku Station is a familiar sight on social media. (Courtesy Nakamura Yukino)

Harajuku Station is a familiar sight on social media. (Courtesy Nakamura Yukino)

Unfortunately, plans are underway to knock down the station and replace it with a modern structure. Despite cries for preservation, the deadline is getting nearer without any solid ideas as to how the station might be relocated or who would pay for such a project.

When train services began in 1906, Harajuku was a small, peaceful outpost. In 1909 it became a stop on the Yamanote Line, and in 1920 the formal opening of the Meiji Shrine made the station a stopping-off point for worshipers to the nearby sanctuary. This prompted the construction of today’s Western-style, wooden station building. The elegant structure was designed by Hasegawa Kaoru, an architect at the Ministry of Railways. The ministry was apparently infused with the sense of freedom and idealism of the Taishō era (1912–26) when entrusting the task to the young Hasegawa.

Nearly a century in operation, Harajuku Station now sees some 70,000 passengers each day. Only around 30% are regulars on commuter passes, demonstrating the powerful allure of the neighborhood.

To relieve congestion, Japan Railway expanded the station building, which straddles the tracks and main platform, and connected a special platform used for New Year visitors to Meiji Shrine to Takeshita Exit on the east side of the station. It also installed new ticket gates on the Meiji Shrine side of the station, increased the number of toilets, and installed new elevators. Reconstruction work is scheduled to be complete before the 2020 Tokyo Olympics.

The revamped station building will presumably be easier to use and less crowded, but judging from early designs it will have a decidedly different atmosphere than its predecessor. Considering the history and popularity of Harajuku Station, why was there no move to adopt a plan that, as with Tokyo Station, blended the old and new?

Harajuku Becomes a Fashion Center

The station building is not all that is changing. The character of the neighborhood is transforming as developers implement initiatives put forward by the Tokyo Metropolitan Government’s Bureau of Urban Development. This year will see the demolition of luxury condominiums and distinctive boutiques on the corner of Omotesandō and Meiji-dōri that epitomized the atmosphere of the 1970s. The Harajuku that was in the forefront of fashion and subculture in the 1970s and 1980s is becoming a distant, sepia-tinted memory.

In the 1950s and early 1960s, Harajuku was little more than a quiet backwater where wild plants grew by the roadside. Oriental Bazaar, a souvenir shop targeting American soldiers from the Washington Heights housing complex in Yoyogi, and toy store Kiddy Land were the only major buildings around. Traffic was so sparse that the US military was rumored to hold landing exercises for light aircraft on the broad avenue of Omotesandō. The decision to hold the 1964 Olympics in Tokyo, however, changed things.

First came the Co-op Olympia Annex. Completed in 1964 just outside Harajuku Station, it was Japan’s first luxury apartment block, boasting round-the-clock management and services available in English. Most of the residents were foreign diplomats , businessmen, and entertainers. Taiwanese pop star Teresa Teng lived there for five years from 1974.

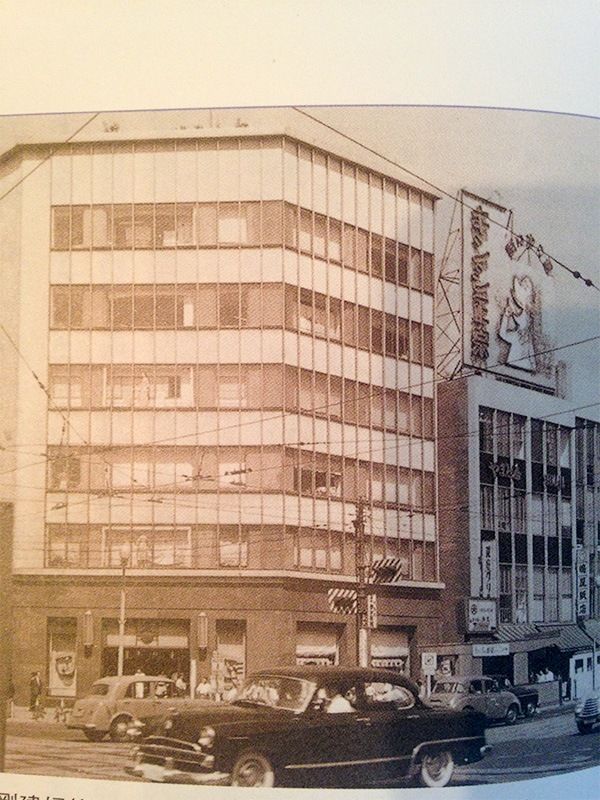

The Co-op Olympia Annex in the 1960s. From the book Fei ying: Riben liuxuesheng zhi mu Ding Weirou (Flying Hawk: My Mother Ding Weirou, a Foreign Student in Japan), by Jin Mingwei.

The Co-op Olympia Annex in the 1960s. From the book Fei ying: Riben liuxuesheng zhi mu Ding Weirou (Flying Hawk: My Mother Ding Weirou, a Foreign Student in Japan), by Jin Mingwei.

Other landmarks followed, including the chalk-white Union Church, Route 5—thought to be Japan’s first drive-through restaurant—and small boutiques like Mademoiselle Non Non and Milk. Chicago, a second-hand store specializing in foreign clothes, was established in the Olympia Annex, and boutique Mako Bis became a must-see fashion outlet on Omotesandō.

In the 1960s Harajuku pulsed with excitement. Its fashion was somehow reminiscent of London, it was friendlier than Roppongi, and was one of the few spots you could find authentic pizza and French fries, still a rarity at the time. I loved Harajuku then and often hung out there.

In the 1970s, designers in the district adapted Western fashions to create new Japanese trends. Harajuku was unique among the world’s fashion centers as a place where young designers could experiment rather than be driven by large corporations, and the stores had a fresh aura of individuality. The area was comparable in stature to street-fashion centers in London and New York and offered visitors new discoveries each time they came. While Shinjuku was known for its jazz, underground culture, and antiwar demonstrations, Harajuku attracted a broad spectrum of young people who came to be part of the bright, unprejudiced, and forward thinking atmosphere. The rock music and low-budget, chic, and idiosyncratic boutiques seemed to promise a new way of living.

A group of young people on Omotesandō sometime in the 1970s. (Courtesy Some Gorō)

A group of young people on Omotesandō sometime in the 1970s. (Courtesy Some Gorō)

After I graduated from university and became an editor, I went to the Harajuku Central Apartments, which stood on the crossroads of Meiji-dōri and Omotesandō, for meetings with photographers, stylists, and illustrators. The building was a center for the offices of creative types with glam and West coast rock playing, and indoor plants on display. There were always the latest sought-after models or actors in the first-floor café Leon.

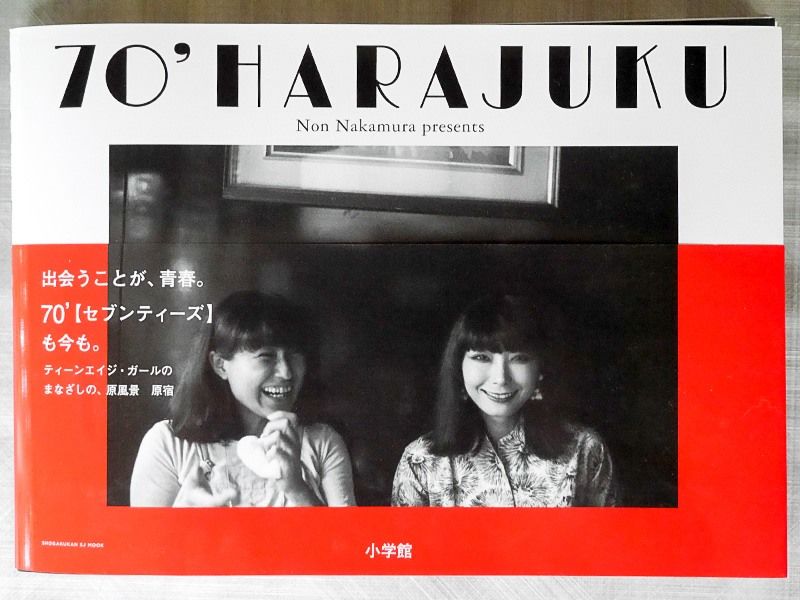

This is exactly the period documented in the photo collection 70’s Harajuku, edited by Harajuku stylist Nakamura Non. Its superb presentation of the youthful vibe that reverberated through the fashion district in the 1970s has made it a steady seller since its 2015 publication.

The photo collection 70’s Harajuku. (Courtesy Hirano Kumiko)

The photo collection 70’s Harajuku. (Courtesy Hirano Kumiko)

As Harajuku’s brand value rose in the 1990s, money poured into construction of fashion retail buildings. The Union Church was demolished, and developer Mori Building erected the Laforet Harajuku mall in its place. The success of the shopping center enticed leading names in the apparel industry to establish branches in the area, turning Harajuku into an essential destination for fashionistas from around the world.

As a result, though, the district’s distinct identity began to fade from around 2000. As commercial buildings and franchises proliferated, stores with unique identities were forced to migrate to the backstreets, known as Ura-Harajuku. Familiar brands came to line the main streets as big business defined the new face of Harajuku.

Concerns for the Future

As part of redevelopment the Co-op Olympia Annex will also be pulled down, most of its tenants having already moved out. Teresa Teng fans from China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan have flocked to the site to take photographs before it is demolished. Tōkyū Fudōsan Holdings, Japan’s fourth largest land developer, plans to build a 22,000-square-meter shopping center on the site that is scheduled to start business in 2020. The company already runs Tōkyū Plaza Omotesandō Harajuku, which opened in 2012 on the site of Central Apartments, and built a commercial complex on Meiji-dōri.

Looking across the crossroads at the Co-op Olympia Annex. (Courtesy Nakamura Yukino)

Looking across the crossroads at the Co-op Olympia Annex. (Courtesy Nakamura Yukino)

The 1964 Olympics were a catalyst for change in Harajuku, and Tokyo’s second games 56 years on have also sparked transformation. However, having spent my youth in Harajuku, I am concerned about where it is heading.

I would love the tourists who visit to see the photographs from the 70’s Harajuku collection. With those pictures of Harajuku’s former sparkling individuality in mind, I hope they would stroll around today’s commercial areas with a sense of the district’s past.

(Originally written in Japanese. Banner photo: Harajuku Station. Courtesy Nakamura Yukino.)