A Prescription for Japan’s Poor Financial Health

Politics Economy- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Chaos continues to buffet the international economy. The Greek debt crisis has escalated into a major problem that now threatens to engulf the entire eurozone, yields on Italian government bonds are rising rapidly, and US Treasury bonds suffered a humiliating downgrade at the hands of one of the major rating agencies. With its current account surplus, Japan is perceived as being in relatively better shape compared to other major economies. As a result, investment is flowing into the country, the yen is growing stronger, and interest rates on long-term Japanese government bonds have fallen even lower than usual. To be sure, stock prices have taken a beating as a result of the strong yen, which has undermined the competitiveness of Japanese exporters. The government and the Bank of Japan carried out an unsterilized intervention (*1) to address this situation, but the intervention was small in scale and has had no discernable effect.

What is the current state of Japan’s fiscal circumstances? Although the ratio of gross government financial liabilities to gross domestic product has risen above 200%, a situation even more serious than Greece’s, interest rates are holding steady. And although the social security bill continues to grow and grow as Japan’s population gets older, there is still no prospect of a tax rate increase in sight. Furthermore, rebuilding after the March 11 earthquake and tsunami will impose an additional burden on public finances. What can be done to stem the flow of red ink?

Two Ways of Looking at Fiscal Deficits

There are a number of ways of looking at this question. Let us begin with two extreme views. The first asserts that government bonds represent liabilities that absolutely must be paid off in one way or another, whether by hiking taxes or cutting spending. At the other extreme are those who insist that government bonds are nothing to worry about—although bonds represent debts from the government’s point of view, from the standpoint of the people who have purchased them they are not debts but assets. Government bonds are often described as liabilities that the current generation is passing on to future generations, but they can also be regarded as assets that future generations will inherit from the current generation. According to this view, the repayment of principal and interest is nothing more than a financial transaction between the government and the people of the future. The funds raised by issuing these bonds today are therefore not taken by the current generation from the future. Think of it like this: If the Japanese population continued to decline at current rates, the very last Japanese person would be born roughly 950 years from now. That person would play the roles of both government and public. In the former role, any outstanding government bonds would be inherited liabilities—but in the latter role, they would be inherited assets. Since the liabilities and assets would cancel each other out, our hypothetical last Japanese would up end with neither liabilities nor assets.

Faltering Steps Toward Financial Health

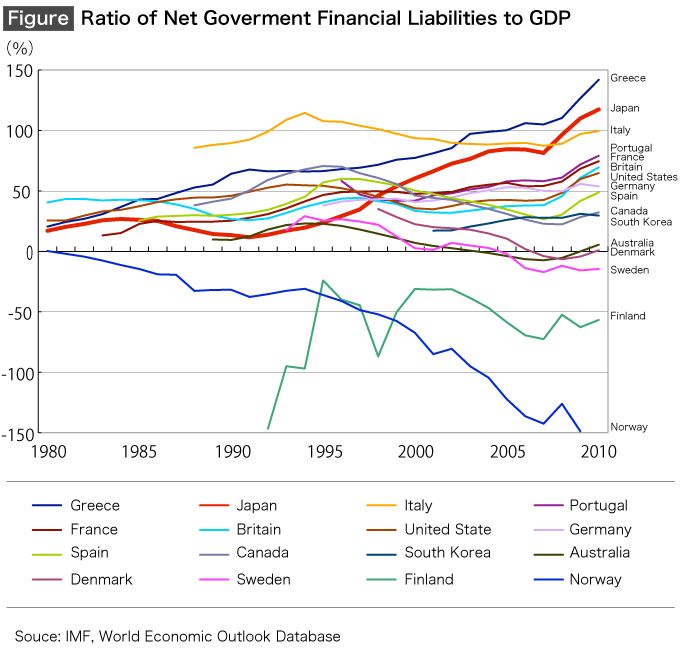

The second of these arguments seems closer to the truth to me, but I could not say with absolute confidence that it is right. When theory proves inconclusive, our best option is to look to the past. The chart plots the ratio between GDP and net government financial liabilities for major economies. Note that these are net liabilities, calculated by subtracting assets from gross liabilities. For example, although the Japanese government is encumbered by heavy debts, it also has abundant assets. Needless to say, net liabilities provide a better measure than gross liabilities of a country’s true financial position. Even by this measure, Japan’s liabilities are substantial—only slightly under the level of Greece. But what is more important to note in this context is the fact that the ratio of Japan’s net financial liabilities to GDP actually fell between 2006 and 2007. In other words, the government’s efforts to regain a sound fiscal position were succeeding. From 2005 to 2007, the ratio fell by 1.5 percentage points annually. If this trend had continued for another 20 years, the GDP ratio would have dropped to around 50%, on a level with the other advanced economies prior to the global financial crisis. There would have been little to worry about.

There were several reasons why the ratio started to rise again rapidly after this promising start. First among them, of course, was the sudden contraction in tax revenue that came about when the global financial crisis caused an economic downturn. The second was the record expansion of government spending that was approved in an attempt to deal with the crisis.

Although other countries responded to the crisis by embarking on radical programs of monetary easing, Japan took only small steps toward easier money. This was the third reason for Japan’s current plight. The policy led to an appreciation in the yen and deflation, which caused tax revenue to fall even further. If other countries put more of their currencies into circulation and Japan does not follow suit, the yen will naturally go up in value against other currencies as a natural consequence of the exchange rate system. A stronger yen means lower profits for Japan’s exporters and less income for the government from corporate tax payments. Falling profits bring job losses, dampening consumption and exerting further downward pressure on prices. At the same time an appreciating yen makes imports cheaper, increasing the deflationary pressure. Once deflation sets in, tax revenue shrinks.

The fourth factor was entirely self-induced. Shortly before the global financial crisis hit, the Japanese government began to increase social security spending without securing the necessary financial resources first. Since social security costs rise as the population gets older, providing more benefits to each senior citizen will naturally cause social security spending to increase exponentially in the future. The ongoing debate that has been underway since the Democratic Party of Japan came to power in 2009 about a combined reform of the social security and tax systems has failed to take this fundamental fact into account. Supporters of reform have simply asserted that social security spending should be increased and that the costs will be covered by higher taxes. If this kind of thinking prevails, Japan’s financial woes will only get worse as the average age of the population increases in the years to come.

Returning to the Years of Success

So how should the authorities have reacted? No economic slump lasts forever. During a slump, a fall in tax revenue is inevitable. Increased government spending on unemployment measures and other components of the safety net can also not be helped. But the government should not have used the economic downturn as an excuse to increase public works spending. Much of this spending was unnecessary, and had negligible effect. If Japan had followed the rest of the world in pursuing a policy of monetary easing, it might have prevented the appreciation of the yen and deflation would not have been so serious. This would have made it possible to avoid a fall in tax revenue caused by an appreciating yen and falling prices. The government should also have stood firm against the idea of increasing old-age social security benefits, as politically difficult as this would have been.

The progress that Japan made in reducing the ratio of net government financial liabilities to GDP during 2006 and 2007 was largely due to the policy of quantitative easing adopted by the Bank of Japan until March 2006. This policy helped to keep appreciation of the yen under control, and stopped deflation from reaching critical levels. As the business climate improved, companies paid more corporate taxes into government coffers and started to hire more workers. This set the stage for increased revenue from personal income taxes and consumption tax. The government also acted to limit spending by downscaling public works projects and keeping a check on social security costs.

In the light of this, it is clear that the best way to restore balance to Japan’s public finances is to return to the economic policies that produced successful results in 2006 and 2007. But it is essential to remember that the pace at which the population is aging will only increase in the years to come. The government needs to make clear that there will be no increase in old-age benefits per person and, indeed, that cuts may be made. The government must also make up its mind to introduce major increases to the consumption tax, which will need to go up by 15 percentage points by 2050, when the aging process is likely to reach a peak. This will mean increasing the current 5% rate gradually to 20%. As the tax rate increases, bringing in more revenue, the government should continue resolutely to keep government spending within the limits of the funds available.

(Originally written in Japanese by Harada Yutaka, Councilor at Daiwa Institute of Research and senior fellow in the Tokyo Foundation.)

(*1) ^ When a central bank buys or sells its own country’s currency and the currencies of other countries to influence exchange rates, the amount of the currency in circulation either increases or decreases. (The money supply increases when a bank sells its own currency and buys foreign currencies, and decreases when a bank buys its own currency and sells foreign currencies.) When the central bank acts to counter such effects by means of open-market operations and other monetary adjustments, thereby stabilizing the money supply and market interest rates and preventing inflation or deflation, the intervention is said to be sterilized. An unsterilized intervention refers to a case of intervention in which monetary adjustments are not made. —Ed.

Harada Yutaka fiscal deficits global financial crisis social security consumption tax