The TPP as an International Public Good

Politics Economy- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Japan has reached a major turning point. Will it follow the path of decline it has been treading ever since its bubble economy collapsed early in the 1990s? Or will it rouse itself and move forward as an advanced nation shouldering responsibility? In order to turn our country around, we Japanese must take a fresh look at our history and accomplishments since World War II and open new paths into the future on a variety of fronts. I would say that one opening to a better future lies in participation in the Trans-Pacific Partnership, also known as the Trans-Pacific Strategic Economic Partnership Agreement.

The TPP represents a steppingstone on the path to the Free Trade Area of the Asia-Pacific, a proposed community that all Asia-Pacific nations would be able to join, and it is the only such agreement for which negotiations have already begun. Participating in the TPP will have great significance for Japan and other countries in the Asia-Pacific, as its creation will bring into being an international public good in this region.

Responding to Change in the World Economic Order

The significance to Japan of taking part in the TPP can be summed up in four points. First, participation will facilitate Japan’s response to change in the world economic order. Europe took the lead in shaping the modern international community around the middle of the seventeenth century, and later it was joined by the United States. The world growth center today, however, is shifting to the Asia-Pacific region. By playing an active role in the economic integration of the region, which needs to increase its productivity, Japan can position itself to take advantage of the region’s growth.

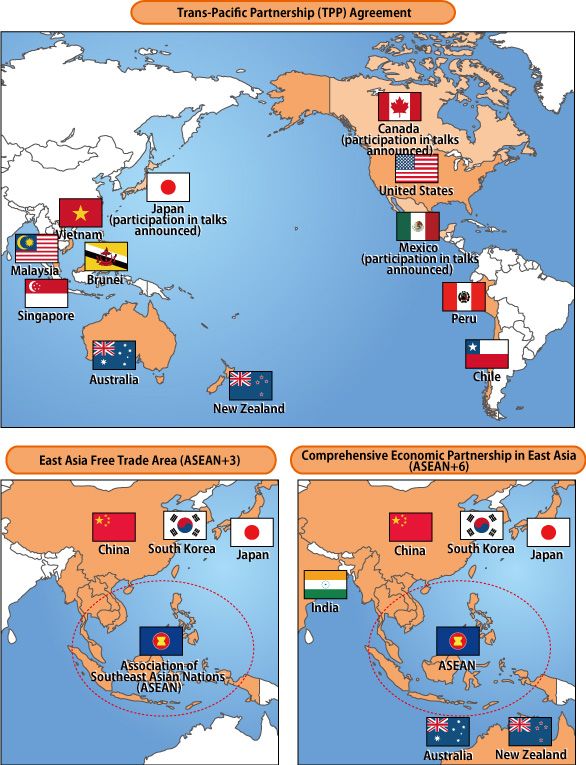

Japan signaled its desire to join the TPP talks in November at the summit in Honolulu, Hawaii, of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation forum (APEC), and it was followed by Canada and Mexico. With their participation, the TPP will be an agreement among 12 parties that together account for about 40% of the world’s gross domestic product. This is significantly larger than the European Union’s 26% share of global GDP, and it is also larger than the 23% share of the ASEAN+3, a group comprising the members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations together with China, Japan, and South Korea. If such a huge economic zone can be realized, it will present Japan with great opportunities.

The Chance to Act as a Rule Maker

The second aspect of the TPP’s significance is that Japan will get a chance to act as a key rule maker in the international community for essentially the first time. In international negotiations to date, including the multilateral rounds of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade and the World Trade Organization, Japan has been a participant but not, unfortunately, one of the leading actors. During the Uruguay round (1986–94) Japan, on account of its economic might, acted as one of the core members along with the United States, the EU, and Canada, but in the end it was shunted aside because of its refusal to budge on agricultural issues. The fact of the matter is that it was driven into a position where it had no choice but to accept the contents of the agreements reached by the other members. In the latest round of trade negotiations among WTO members, the Doha round (2001–), our country is not even considered to be a core member. Its presence as a rule maker for international trade has become greatly diminished.

We should nonetheless note that Japan remains actively involved in the arena where economic integration in the Asia-Pacific region is moving forward. Apart from its plan to join the TPP, it is a participant in both the ASEAN+3 and the ASEAN+6 (ASEAN plus Australia, China, India, Japan, New Zealand, and South Korea). In addition, it has entered into numerous free trade agreements and economic partnership agreements with other countries in the Asia-Pacific and is pursuing a high-level FTA with China and South Korea. Japan is thus establishing a suitable position for acting as a rule maker in the creation of a free and open trade and economic order for the overall region.

The TPP came into being at the initiative of the four small countries of Brunei, Chile, New Zealand, and Singapore. Now that the Doha round has stalled, the TPP not only has grown in scope to the point where it covers a broad group of countries but also has potential for stimulating the world economy as a whole by creating a free and open international trade and economic system on a higher order than has been realized to date. And Japan holds the key to its success.

The TPP’s Potential as a Public Good

Third, when we look at the TPP in this way, we see that it can be and needs to be an international public good in the Asia-Pacific. Some observers view the TPP as an arrangement meant to counter China’s growing power, but that is incorrect. China will also benefit from the realization of a free and open international trade and economic system in the region. In fact, Tokyo ought to take the lead in getting Beijing to recognize that the TPP will have future merits for China and that it, too, should take part in the agreement.

Because Washington’s cooperation will be essential for this, Japan must understand that it needs to encourage the United States to become more deeply committed to the Asia-Pacific region. The administration of US President Barack Obama, seeing the United States as an Asia-Pacific nation, is in the process of staking out a position of constructive regional engagement in various spheres, politics and security included. As an ally of the United States, Japan needs to give all the support it can to this shift in US diplomatic strategy in the Asia-Pacific direction.

Some people in Japan see the TPP talks as a ploy by Washington to get Tokyo to do its bidding. This argument, though, is grounded in the perception that Japan is always being victimized, a viewpoint welling from complicated historical factors. Diplomatic negotiations invariably begin with a confrontation between the stances and assertions of the respective parties, and to assume that Tokyo will inevitably lose out to Washington would be to subscribe to the defeatism that has long had many Japanese in its grip. We should see it as nothing more than a manifestation of our old inferiority complex toward the Americans. We Japanese should have more confidence in our nation’s strength and reputation; we should demonstrate that Japan has the mettle to join in international rule making together with other countries that share its values. The TPP represents a window of opportunity for a switch to proactive diplomacy, and we ought not to let this chance slip from our grasp.

An Opportunity for Domestic Reform

The fourth aspect of the TPP’s significance is the opportunity it has presented for moving forward on domestic reform. Participating in the agreement will naturally have painful consequences in some quarters. It is a broad agreement covering some 21 areas, including agriculture and medical care, and it involves an assortment of thorny issues. At the same time, however, it should give Japan an excellent chance to tackle reform of domestic industries and institutions.

Especially in the field of agriculture, reform is imperative to turn it into a strong, export-oriented industry. If we continue along the course of taking shelter in protective policies, we will find that strengthening agriculture simply cannot be done. Cherries and apples offer two examples of how market opening can facilitate the development of competitive products. The policies the government ought to be promoting are those capable of realizing the latent competitiveness of Japanese agriculture. To be sure, there must be adequate domestic debate over the merits and demerits of opening markets and changing systems and practices, and in talks with other countries there must be discussion of the application of grace periods and other such measures for the products and sectors that each country sees as sensitive. Provided that the Japanese government thrashes the issues out through domestic discussions and international negotiations and takes adequate steps to redress the pains entailed, it should be possible to persuade the Japanese people of the need for change.

Embracing the TPP with Open Arms

When the Tōhoku region of northeastern Honshū was hit by an earthquake and tsunami in March 2011, some 160 countries stepped forward with offers to send help. We should take this as an expression of appreciation from the world for the achievements Japan has accomplished in the postwar period, when it rebuilt itself from the destruction of World War II, and for the major contributions it has since made to the international community. Surely it was also an expression of hope that Japan will not let this natural disaster get it down and that it will continue to play a major global role, bearing a commensurate measure of responsibility. It seems to me that the rest of the world, recognizing that Japan now stands at a fork in the road, is urging us to do all we can to overcome the problems. It behooves us to respond to this message of encouragement by playing an active part in the TPP.

United States China TPP APEC ASEAN+3 ASEAN Asia-Pacific Trans-Pacific Partnership Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation Free Trade Area of the Asia-Pacific FTAAP Association of Southeast Asian Nations ASEAN+6 Barack Obama