China’s New Leadership: Sensing a Crisis but Choosing Not to Act

Politics- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

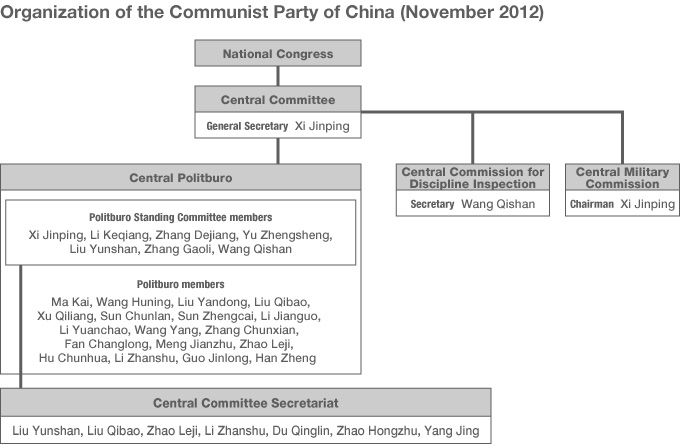

The Eighteenth National Congress of the Communist Party of China came to a close on November 14, 2012. The Eighteenth CPC Central Committee selected by the congress held its first plenary session the next day and elected the members of the CPC Central Politburo. This marked the start of the regime of Xi Jinping, the new CPC general secretary.

Media organs around the world competed to be the first to unveil the new members of the Politburo Standing Committee, the most powerful decision-making body in China. As had been expected, Xi Jinping (59) and Li Keqiang (59) retained their seats. Five members were newly elected to serve with them: Zhang Dejiang (66), Yu Zhengsheng (67), Liu Yunshan (65), Zhang Gaoli (66), and Wang Qishan (64). This gives the PSC seven members; two fewer than there were previously.

Many Japanese newspapers interpreted the new lineup as a smashing victory for the “Shanghai clique” among the CPC factions, pointing out that six of the seven members are allies of Jiang Zemin, CPC general secretary from 1989 to 2002. But is this really how we should view the new cast of leading actors?

Frosty Treatment of Japan Unrelated to the Personnel

Observers in Japan were watching the personnel selection in the Eighteenth National Party Congress to see which of the factions in the top leadership would emerge with the greatest representation. Policy decisions are made through group consultations influenced by majority rule so the presumption is that the key to China’s course over the next 10 years will lie in whichever faction has the greatest numbers.

On seeing the results of the selection process, the Japanese media quickly delivered their verdict. The harsh feelings toward Japan in party circles, we were informed, are sure to become yet harsher. The reasoning for this is that the new PSC consists for the most part of followers of Jiang Zemin, who is said to dislike Japan for personal reasons. It can therefore be expected to steer a course of hard-line policies toward Japan.

Actually, though, is it not true that the currently chilly relationship between Japan and China began with little connection to the composition of the standing committee? It was in September 2012 that the souring of the bilateral ties became plainly evident. At the time, the Japanese media sought to explain the change by saying that Jiang’s clout in the CPC had grown stronger or that the new stance was evidence of the considerable influence he still retains. But if that is the case, it follows that Jiang is fully capable of getting his way regardless of the PSC’s composition, and there should have been no need to place even more of his protégés on the standing committee.

Tempest in a Teapot

Quite a few Japanese media organizations now regard General Secretary Xi Jinping as a member of Jiang’s Shanghai clique, but not that long ago he was seen instead as part of “princeling faction”—the children of the revolutionary heroes who founded the CPC. That made him a comrade of Bo Xilai, former Chongqing party chief and Central Politburo member. The idea at the time was that government policies in China are shaped through a three-cornered contest involving the Jiang faction, the princelings, and the “Youth League faction” led by Hu Jintao, general secretary from 2002 to 2012.

Somewhere along the way, however, this picture of factional rivalry ceased to provide a coherent explanation of actual political developments. Emblematic of this is Bo Xilai’s sudden fall from power. Against this background, the reports predicting that henceforth the Jiang faction will rule China as it pleases must be branded as exceedingly irresponsible. Here, accordingly, I will distance myself from the faction-first style of China analysis in order to take a fresh look at the situation now confronting the CPC as an organization.

Of course, any overhaul of the leadership lineup is bound to entail clashes of interests and engender friction. The key question, though, is how much weight should be put on the shake-up when projecting China’s future policy course. Whatever the situation was five years ago, public opinion has now replaced the Communist Party as the country’s leading actor. I would therefore say that such issues as the jockeying for top party positions amount to little more than a tempest in a teapot.

Eradicating Corruption at the Top of the Agenda

In this context, what was the most salient feature of the eighteenth party congress? My answer is that it was the CPC’s stance toward self-reform, a stance with a strong impact on the trust the Chinese people place in it to serve as the nation’s ruling party.

On the opening day of the party congress, outgoing General Secretary Hu Jintao delivered a keynote political report. Touching on the most vital issue at the congress, he warned, “If we fail to handle [corruption] well, it could prove fatal to the party, and even cause the collapse of the party and the fall of the state.” Upon taking over from Hu, Xi Jinping also laid emphasis in his first press conference on the need to root out corruption. This issue, we may safely say, has become a common concern in the party.

Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao has also highlighted the problem. At the close of the National People’s Congress in March 2012 he stated, “Without successful political structural reform, it is impossible for us to fully institute economic structural reform. And the gains we have made in this area may be lost.” This is an expression of a sense of crisis deriving from the same context.

Further evidence of the party’s sense of crisis can be found in the security measures put into place shortly before the party congress opened in Beijing. Their unusual stringency drew much comment. Prior to the event, the city’s taxi companies were ordered to remove window handles so that passengers could not open their windows, a measure aimed at preventing antigovernment activists from distributing leaflets critical of the party. People moving around Beijing by subway were subjected to questionings and baggage inspections, and those entering the city by train went through four security checks. In order to buy a remote-controlled helicopter at a toy store, customers had to present IDs.

Guangdong Reformer Wang Gets Excluded

Obviously the party leadership was on the lookout for a crisis in one form or another. When the personnel selection at the party congress is examined from this perspective, it is disturbing to see the treatment accorded to Wang Yang, party chief of Guangdong Province. He is a Politburo member who reportedly was on the short list for the PSC but ultimately dropped off it.

It is no accident that Wang Yang has been in charge of Guangdong for the past five years. After all, Guangdong is the laboratory in which new ideas are first tested. Because it lies far from the center of power on the southern coast and has some of China’s leading cities, it is a convenient place for experimenting with reforms that would run into resistance if conducted in Beijing. While administering Guangdong, Wang has launched a number of bold initiatives that have placed the province in the vanguard of political reform.

Shortly after his arrival late in 2007, Wang pushed the concept of “thought liberation” to the fore. In a speech he delivered in December, he laid heavy stress on the need to go even further along China’s reform and opening line. While acknowledging that pursuing reform could be a “bloody road,” he issued a call to arms with the phrase jiefang sixiang (thought emancipation), which he used 22 times in his address.

The reforms Wang has initiated extend over a broad area, starting with the introduction of direct elections for key local public officials. He has reformed the Guangdong People’s Congress, the provincial committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, and the organization of the judiciary. In addition, he has established a system for preventing corruption. In addition, he has initiated discussion on reforming job categories in the civil service and broached the idea of changing the electoral system for district heads and mayors so that a certain percentage of the candidates fail to get elected. On repeated occasions, moreover, he has declared that the media play an important role of monitoring the authorities.

One of his singular accomplishments, however, may have been his undoing. When the villagers of Wukan rose up in protest at the grabbing of their land by local officials, the police used force to quell the disturbance. Local residents became so angry that the dispute escalated into a riot and for quite a while the functioning of the village was paralyzed. Eventually Wang agreed to a village election, and the protest leader was elected as the new village party chief. The news of the uprising and its successful resolution spread around the world, putting the central leaders of the CPC in an uncomfortable position. It was reported that they—particularly the party elders—abruptly turned against Wang. The Wukan protests, some senior leaders in Beijing argued, degenerated into turmoil because the local authorities failed to show sufficient resolve in putting the troublemakers down. In this way, Wang stood accused of making a typical policy blunder. With his credentials as an administrator in doubt, he was passed over as one of the seven PSC members.

Picking Leaders Who Will Uphold Traditional Values

While China does not release official statistics on incidents of civil disorder, what it calls “mass incidents”—an overall designation for protests and physical clashes involving three or more people—are thought to occur more than 200,000 times per year. Under the circumstances, there are limits to responses based on putting down protests through a resolute show of force. Before Xi Jinping’s new administration was one week old, major riots had already broken out in Fujian and Zhejiang provinces. Police cars were destroyed and local leaders were harshly denounced.

In such a situation, we should not be surprised that party members fear a crisis could develop if serious reforms are not carried out. This was the message Hu Jintao delivered in the political report I mentioned earlier, when he spoke repeatedly of the need to free up minds and think innovatively. This is not to say, however, that the sense of crisis has grown so acute as to trigger questioning of the traditional values of the ruling party. Even as he warned of a crisis in his address, Hu spoke of the role of the party in highly affirmative terms. He expressed his full confidence in the path, the theory, and the system of socialism. In short, he said the party was on the right track and could safely proceed on as before.

What we can see here is a party with a disposition to do nothing even as it senses an impending crisis. Indeed, this may be the essence of the overhaul of the party’s leadership. Similar self-contradictory phenomena are also in evidence in Japanese society, where a generational gap has given us a young generation sensing that a crisis is on hand even as the old generation, while not oblivious to the problems, is content with inaction.

In a setting of public discontent with economic inequalities, which Bo Xilai’s brief rise brought into clear relief, the CPC opted to provide the new Xi Jinping regime with a set of leaders who have rejected a leftist return to the era of Mao Zedong but who have also turned down the radical reforms proposed by Wang Yang. Perhaps we should say that in the end, they selected a balance based on sustaining traditional values.

(Originally written in Japanese on November 22, 2012. Title photo: New General Secretary Xi Jinping delivers an address on November 15, 2012. [Photo: Mark Ralston/AFP/Jiji])

China politics Communist Party of China Hu Jintao Xi Jinping Bo Xilai Tomisaka Satoshi Jiang Zemin Wang Yang