Confronting China’s Island-Building Campaign

Politics- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

A Startling Video

On May 21, CNN caught the world’s attention when it broadcast footage taken from a US Navy P8 patrol plane of artificial islands China is building on coral reefs in the South China Sea. Nine days later, at the Asia Security Summit (Shangri-La Dialogue) in Singapore, US Defense Secretary Ashton Carter’s demand for an immediate stop to island-building activities met with an emphatic rejection from Chinese representative Admiral Sun Jianguo, deputy chief of staff of the People’s Liberation Army General Staff, as US-China tensions mounted. On June 8 the Group of Seven summit gave voice to the international community’s stern disapproval of China’s actions with a Leader’s Declaration that stressed the importance of “free and unimpeded lawful use of the world’s oceans,” stating, “We strongly oppose the use of intimidation, coercion, or force, as well as any unilateral actions that seek to change the status quo, such as large scale land reclamation.”

China’s Need for Islands

Media reports indicate that China is carrying out land reclamation on seven reefs in the Spratly Islands in the South China Sea. Judging from earlier photographs released by the Philippine government, which provided the first evidence of these activities, the project must have been underway by late 2013. For roughly two years China continued its work surreptitiously, but the recent footage has brought its activities to widespread attention.

In recent years, China has claimed sovereignty over most of the South China Sea, including all of the islands that fall within a “nine-dash line” it has drawn around the area.

In the aftermath of World War II, South Vietnam and China both claimed ownership of the Paracel Islands in the northern part of the sea, but in 1974—in the final stages of the Vietnam War—China defeated South Vietnamese forces in the Battle of the Paracel Islands and assumed practical control.

In 1988, after a naval skirmish with reunified Vietnam, China gained control over a group of reefs and rocks in the Spratly Islands, a disputed archipelago just south of the Paracels. Vietnam, the Philippines, Taiwan, and Malaysia still controlled the archipelago’s 13 major islands, and since most of the reefs and islets China seized were submerged at high tide, they could not be used as baselines for establishing territorial waters under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. Still, China had gained a toehold on the Spratlys and an important base from which to assert its sovereignty over the area.

Lacking a military base in the vicinity, however, China was in need of a more substantial piece of land. But military invasion of any of the four main islands—all of which have runways (however small) controlled by Vietnam, the Philippines, Taiwan, and Malaysia—would have been patently unacceptable for a permanent member of the UN Security Council. So China lit on an alternative: to build its reefs into islands in a dexterous bid to support its claim to legitimate sovereignty.

Balance of Power Tilting to China

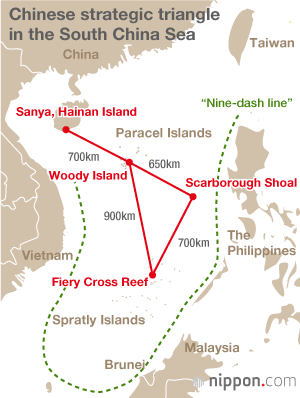

Sanya on southern Hainan Island provides a rear, but core, logistic base for Chinese expansion into the South China Sea. It is home to Asia’s largest naval base, equipped with state-of-the-art facilities, as well as an airbase. Woody Island (known in China as Yongxing Island) in the Paracel Islands lies around 700 kilometers southeast of Sanya; land reclamation has helped to convert it into an advance base with an airport boasting a 2.5 kilometer runway and a port capable of docking large warships. In the central and southern South China Sea, however, China has no such base, and its military presence is currently restricted to limited deployment of naval vessels.

China’s land reclamation efforts in the Spratly Islands are centered on Fiery Cross Reef and the six reefs that surround it within a 200-kilometer radius. The reclamation project has made considerable progress and is nearing completion. There is a strong probability that China will build an airbase with a 3-kilometer runway, taxiway, apron, and storage facilities for fuel and ammunition on Fiery Cross Reef, as well as a thoroughly capable port. The other reefs will serve to protect Fiery Cross Reef by monitoring the surrounding sea, supplying early warning, and providing defensive support.

When the entire project is complete, China will have a significant naval installation and airbase in the Spratly Islands. Moreover, instead of a single point at Woody Island, it will have a north-south line running 900 kilometers between Woody Island and Fiery Cross Reef. This alone is clearly enough to tilt the military balance of power in the South China Sea significantly in China’s favor. Washington’s recent hardline stance toward China reflects its acute concern over this point.

If the international community is unable to prevent further island building, the next step could be reclamation and base building on Scarborough Shoal, about 200 kilometers off the west coast of the Philippines, which has been under the practical control of the Chinese since 2012. For the United States, which has no genuine strategic bases in the massive expanse of ocean west of Okinawa, this is an alarming prospect, since the bases on Woody Island, Fiery Cross Reef, and Scarborough Shoal would allow China to assert control over a triangular area 650–900 kilometers on each side.

Expanded Operating Area for Strategic Nuclear Submarines

In addition to altering the US-Chinese balance of power in the South China Sea, China’s island building threatens to expand the operating area for Chinese strategic nuclear submarines deployed from Sanya into the Pacific and Indian Oceans. This disruption of the strategic nuclear balance could have a serious impact on the global security situation.

The political and economic consequences are also extremely troubling. If the international community accedes to China’s unilateral claim to sovereignty over the sea within the nine-dash line in defiance of international norms, it could undermine the international maritime order that has supported global prosperity. It could also destabilize the region by reinforcing China’s adventurist proclivity for altering the status quo by force. And it could allow China to limit and control freedom of navigation in the South China Sea, violating a universal right.

What Japan Should Do

As the foregoing suggests, China’s establishment of military bases in the South China Sea has implications for Japan that extend beyond the field of security to every realm of activity. Although one can well imagine that China will be reluctant to abandon the undertaking, given the strategic importance it attaches to the South China Sea, Japan must direct every effort to stopping these illegal activities.

Restraining China’s self-serving adventurism will require political and diplomatic measures in tandem with military and defense capacity building. The US military presence in the region and Japan’s support for the American forces are the keys to this capacity.

The US military is already beefing up its force deployment and operational structures in the region while strengthening security ties with Asia-Pacific countries as part of the current administration’s rebalancing policy. Since US troops in South Korea must be prepared to react to developments on the Korean Peninsula, any response to changes in the South China Sea would have to be handled by forces stationed in Japan or deployed from the United States itself. Japan must not only offer its full support for the US military presence in the region but also build institutional frameworks to enable the Self-Defense Forces to collaborate fully with the US military units that would lead any strategic action in the event of a crisis or emergency.

Bringing China to the Negotiating Table

As the “shield” to the US military “spear,” the SDF are required to reliably perform the twin roles of protecting Japanese territory—through ballistic and cruise missiles and island defense—and maintaining sea lane defense to secure their own safety and support the United States. Should the US military lead a strategic strike against China in the South China Sea or elsewhere, US-Japanese strategic coordination would be vital. Japan should boost both the SDF’s ability to defend Japanese territory from the Chinese threat and their ability to protect sea lanes in the western Pacific, thereby enabling US forces to operate over a wider area. This would significantly increase the flexibility of the Pentagon’s strategy for containing China and create a stronger deterrent. Recently there has been discussion in the Diet and elsewhere concerning surveillance of the South China Sea. The United States should continue to play the leading role here, but in the limited circumstances where it is difficult for the United States to fulfill its role, it would be appropriate for the SDF to carry it out, given Japan’s situation today and in the foreseeable future.

Among the factors contributing to China’s expansion in the South China Sea are serious deficiencies in the maritime capabilities of other countries in the region, particularly the Philippines and Vietnam. There is also an urgent need for all of the neighboring countries to increase their air and maritime domain awareness. Given their limited resources, however, it must fall largely to Japan and the United States to build a mechanism for gathering and sharing AMDA information for this vast area.

China views the United States as the key obstacle to its strategic goals in the region. It objects to what it refers to as “outside meddling” in the “local” issue of the South China Sea precisely because it understands the weight of US power and expects to compete with it in the future. While our efforts to resolve the issue in the South China Sea should focus on political and diplomatic solutions, defense and military capabilities are needed to support those efforts. Only the certain prospect of involvement by the US military and a buildup in defense capacity by other countries in the region will force China to the negotiation table at long last to discuss the South China Sea issue seriously. Japan’s role in supporting both the United States and the lesser powers of the region is critical to achieving a resolution of this problem.

(Originally written in Japanese and published on July 28, 2015. Banner photo: Chinese island building underway at Fiery Cross Reef with runway progress visible to left. Photograph taken in early May 2015, provided courtesy of the Philippine military [via Jiji].)United Nations United States Self-Defense Forces China Taiwan South China Sea Philippines US military Vietnam national security Malaysia defense