The JOCV Program: Experience of a Lifetime

Politics- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

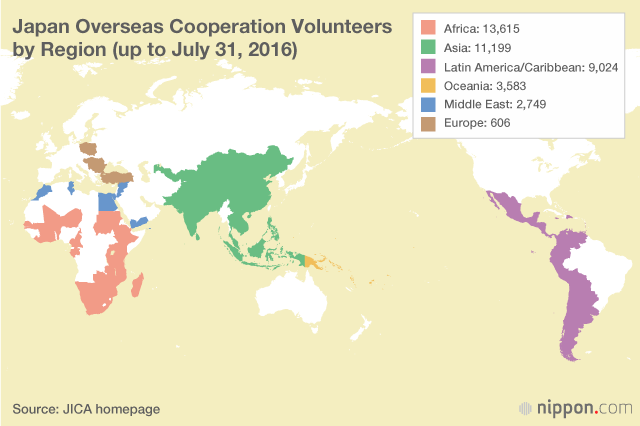

Since its establishment over a half century ago the Japan Overseas Cooperation Volunteers program has dispatched over 40,000 young Japanese men and women, aged 20—39, to 88 developing countries in Asia, Africa, Latin America, Oceania, and other regions. The long life of this program owes much to the trust that the Japanese volunteers have won through their deep involvement at the grass-roots level. The efforts of JOCVs have fostered mutual understanding between Japan and partner countries, making the program an important pillar of Japanese official development assistance.

The Starting Point for a Career in Journalism

I became a JOCV in 1972 at the age of 20. My assignment was to serve as a camera operator for Ethiopia’s national television broadcaster. Like many of my fellow volunteers—there were 24 who joined at the same time—I had never set foot outside of Japan and felt considerable trepidation as I arrived at my post.

Though I had received three months of language classes and other training before leaving Japan, I was totally unable to converse with confidence. On my first day at the television station, I found that I could not understand what my manager was saying, and I was reduced to phoning an English-speaking friend to act as an interpreter. I eventually found my footing, however, and by the end of my volunteer tour I was capable of leading a week-long seminar for other cameramen at the request of the Ethiopian minister of communication and information.

After returning to Japan, I joined a newspaper company, where over the years I have covered stories in 68 countries, including the Gulf War, the United Nations peacekeeping operation in Cambodia, the strife in Rwanda, the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, and the strife in Rwanda, and based on this I have come to be known as a war correspondent. The starting point for this career was my experience in Ethiopia as a JOCV.

In 1972 the author was dispatched to work at Ethiopia’s national broadcaster as a JOCV. Here he fords a river with local porters.

In 1972 the author was dispatched to work at Ethiopia’s national broadcaster as a JOCV. Here he fords a river with local porters.

The Program’s Roots

The JOCV program is implemented by the Japan International Cooperation Agency, a mainstay of Japan’s official development assistance program. It was launched in 1965, and in its inaugural year 40 volunteers were dispatched to five developing countries: Cambodia, Kenya, Laos, Malaysia, and the Philippines.

The initiative is commonly thought to have been inspired by US President John F. Kennedy’s creation of the Peace Corps in 1961. In truth, though, the roots of the JOCV program go back much further.

Following World War II, youth associations and other private-sector organizations undertook domestic volunteer efforts aimed at repairing the devastation from the war and promoting personal, social, and national development within Japan. Then, after Japan joined the Colombo Plan, a cooperative partnership for economic and social development in Asia and the Pacific, in 1954 and launched a small-scale international cooperation program, the government called on youth association members to take part in exchanges and cooperative efforts undertaken as part of this fledgling program of development assistance.

The financial and administrative burden of this involvement, however, weighed heavy on these private-sector bodies, and there were calls for the government to take charge of the activities. It was as the authorities were in the process of planning an initiative in response to these calls that President Kennedy launched the Peace Corps. And this US move may be credited with spurring on the realization of Japan’s planned initiative with the establishment of the JOCV program.

The US Peace Corps was not the only organization dispatching volunteers to developing countries. At the time, just about all the advanced Western nations were providing this sort of support through civil-sector and religious organizations. The wave of development assistance was motivated in part by the Cold War. Both the US-led Free World camp and the Soviet-led Communist bloc used foreign aid as a strategic tool to promote their political and social ideologies overseas. The JOCV program, however, differed from other countries’ initiatives in that most volunteers had practical skills and knowledge in at least one of more than 100 areas. This was a sensible approach: Japanese volunteers might not be fluent in foreign languages, but they were in a position to share Japan’s expertise as a science-and-technology-based nation.

Barriers to Volunteering

The JOCV program has received good assessments. In a JICA survey from 10 years ago the initiative enjoyed a 98% favorability rating among partner countries, compared to a 64% average for all international volunteer programs. I believe this strong showing reflects the disposition of the Japanese volunteers, who focus on the perspectives of the local people around them. In addition, Japan has a track record as a former developing country that achieved advanced status at an early stage. In this respect it may be viewed as a role model by people in today’s developing countries.

It is important, however, to acknowledge that volunteers face an array of challenges and concerns. One is the problem of finding a job after returning to Japan. Under the lifetime employment system that prevails even now at most major Japanese companies, new employees are recruited straight out of school, and people who leave their jobs tend to be looked down on. But only about 20% of volunteers are able to stay on at their companies while participating in the JOCV program. In stark contrast to Peace Corps experience in the United States, which bolsters a resume, time as a JOCV can have serious repercussions on former volunteers’ careers. Even if they get hired again, it is hard for them to advance to core positions in their companies. And given potential volunteers’ concerns over their reemployment prospects, the state of the Japanese economy also has an impact on recruitment numbers, which declined in the wake of the 2008 economic downturn.

Terrorism is another issue. Seven Japanese volunteers were among the 29 killed in the July 2016 terrorist attack in Dhaka, Bangladesh. The victims did not include any JOCVs, but the resulting sense of danger is bound to affect the program’s recruitment efforts.

How the Program Has Changed

The JOCV program has changed in many ways over its five decades. One trend I have noticed is the increased emphasis on assuring the safety of volunteers. When I joined, there was still a “frontier” spirit, and it was common for lone JOCVs to be dispatched to extremely remote regions. But the program is now steering clear of such assignments; it seems that initiatives in remote areas are being left up to nongovernmental organizations. A positive development, though, is that female participants have increased to about half of JOCVs, compared to 10% in my day.

The program has seen a shift away from volunteers experienced in agriculture, fisheries, and other primary industries and toward people from such sectors as education, services, and information technology. The role of regionally based JICA officers has also changed. No such officer ever visited my workplace during my two-year stint in Ethiopia. But now, I hear, they come to check on the volunteers at work once a month. JICA is exercising more managerial oversight, and volunteers have less freedom.

One thing that has remained constant, though, is the personal enrichment that volunteers gain from their participation. Many former JOCVs report that, though they went to give (provide training), they ended up getting back more than they gave. Doubtless this is because they gained valuable experiences that would be hard to have in Japan, where goods are so plentiful and life so convenient..

An Opportunity for Personal Growth

My JOCV experience played a major role in shaping my view of the world, which may be summed up in these four points: (1) Today’s world is a living museum of history. (2) Humans have been advancing from unawareness to awareness. (3) The “class of 40” rule applies to every ethnic group. (4) People are 90% the same; the 10% portion by which they differ is what we call “culture.” Let me briefly explain:

First, in Ethiopia I met nomadic tribes that gave me a glimpse into the lives of prehistoric Japanese of the Jōmon period. With my own eyes I saw a way of life that I had thought was to be found only in history texts. And as I looked around the country from region to region, I found that many other periods of Japan’s past were mirrored in the lives of today’s Ethiopians.

Second, as subsequently I traveled around the world, I came to believe that the human condition is marked by a progression from unawareness to awareness. Education creates this awareness, which in turn creates civilization.

Third, the “class of 40 rule” refers to my conclusion that, regardless of ethnicity, if you bring 40 people together, you will find one who is clever, one who is weird, and one who is handsome or beautiful. This proportion prevails around the world.

And fourth, though some say people are all the same, the similarities account for 90% of what people are, and the other 10% consists of differences. It is these differences that constitute culture. The similarities arise from the basic drives that all humans share, while the differences that give rise to local cultures are produced by the natural environment, which varies from country to country, resulting in variations in lifestyles and ways of thinking.

The JOCV experience is a grand journey of discovery and a source of personal enrichment. The program promotes the growth and development not just of people in developing countries but also of the young Japanese who participate.

(Originally published in Japanese on November 16, 2016. Banner photo: A Japan Overseas Cooperation Volunteer (center) in Sri Lanka together with students in her computer class. All photos courtesy of the Japan International Cooperation Agency.)