Koizumi Jr.’s Quixotic Quest for Agricultural Reform

Politics- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Koizumi Shinjirō was an agricultural policy novice until just a year or so ago, but the popular young lawmaker is now visiting farms across the nation with reform in mind. In October 2015, the son of former Prime Minister Koizumi Jun’ichirō was appointed director of the ruling Liberal Democratic Party’s agriculture and forestry division. Since then, he has thrown his energies into making firsthand observations of farming in action. In August 2016, he began a second term after expressing a strong desire to remain in his post, although LDP members usually switch positions after a single term.

Breaking a Taboo

During a recent Diet debate concerning the Trans-Pacific Partnership, most lawmakers both from the ruling and opposition parties who stood to ask questions on the administration’s policy were backed by agricultural interests. The Diet’s Committee on Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries comprises members on a wide political spectrum from the LDP to the Japanese Communist Party. Yet they are all essentially mouthpieces for the agricultural industry with almost identical opinions. They insist that farmers’ incomes need to be raised and that agricultural product prices must not be allowed to drop. They are particularly intent on maintaining the high price of rice, the country’s staple crop, through gentan policies aimed at reducing rice acreage and cutting supply. Hefty tariffs are also needed to ensure that the prices of domestic agricultural products remain competitive.

Amid a host of questions from lawmakers prioritizing the interests of the farm lobby, a question from Koizumi Shinjirō stood out. He said that he failed to understand why farmers have to pay so much for supplies when the Japan Agricultural Cooperatives (JA) group was originally established to ensure affordable prices.

This kind of question is taboo, and few politicians will make an issue of the large sums farmers must pay for necessary supplies. A few years ago, I became the first Japanese agricultural researcher to note that farmers in this country pay twice as much as their American counterparts for such essentials as fertilizer, pesticide, machinery, and animal fodder.

In Japan, the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries, the JA, zoku lawmakers backed by the farm lobby, and agricultural researchers form what could be termed the agricultural mura (village) having a common destiny and the same interests. The JA helps lawmakers get elected, they in turn ensure MAFF budget appropriations, and the ministry maintains high rice prices and provides subsidies in line with the JA’s wishes. Academics—mainly agricultural economists—receive high speaking fees and other support from the JA and advocate policies favorable to the mura from an ostensibly neutral standpoint. There are some agricultural economists who argue that they should study evidence rather than discussing policy, but many take political positions that benefit the mura. None have conducted evidence-based research on either the cost of farming supplies or what the price of rice would be without a gentan policy. It was unthinkable to conduct research that might lead to results that would harm the farm lobby.

Self-Serving Policies

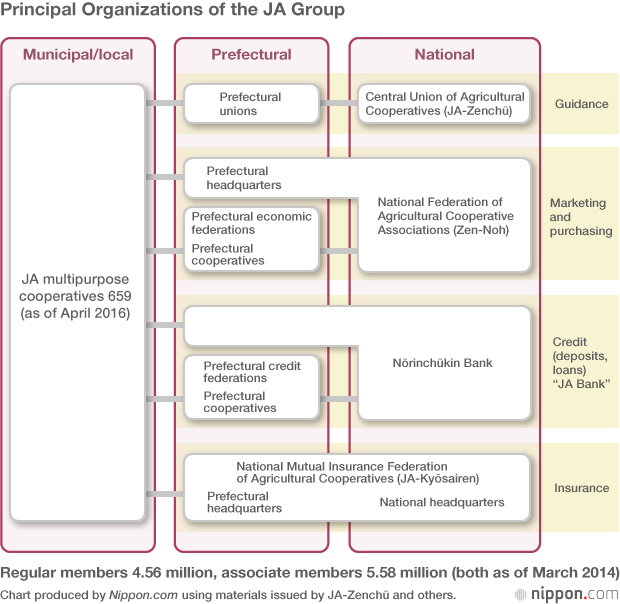

The JA is at the heart of the agricultural mura. It is a unique organization, both compared with other corporate bodies in Japan and with foreign cooperatives. In Japan, ordinary commercial banks are not permitted to engage in other businesses. Western agricultural cooperatives specialize in a particular area, such as sales of agricultural products, purchase of supplies, or agricultural financing. There is no body quite like the JA with activities ranging from savings and financing via banking services to life and damage insurance, produce sales, supplies procurement, and the provision of everyday commodities and services.

Farm lobbies exist in the West as well, but they do not themselves conduct business operations. The JA not only enjoys exclusive economic privileges but also engages in political activities. As a result, it has come to lobby for its own benefit rather than for that of farmers. A journalist once asked me, “Western countries have switched from protecting agriculture through maintaining high prices to providing direct payments, so why can’t Japan do this?” After thinking about this for a day, I realized that the deciding factor was an entity found only in Japan: the JA, with its wide-ranging business activities and strong political voice.

The JA served itself by promoting high rice prices, which allowed part-time farmers to continue working on tiny plots that were expensive to cultivate. During the week these people would work at offices or perform other full-time jobs and tend to the farm during their spare time on weekends. This prevented the rice farming population from declining, so the JA was able to maintain its membership numbers. It also helped to elect conservative lawmakers. Rice farmer members of the JA put their income from other jobs and pensions into JA Bank deposits, together with profits from selling farmland to commercial developers amounting to trillions of yen each year. Even as agriculture, particularly rice production, went into decline, the JA thrived. The huge JA Bank now competes for the title of Japan’s second-largest financial institution.

Arguably, the JA thrived not in spite of the decline of agriculture but rather by instigating its downturn. The JA’s special status and promotion of high rice prices—enabling farming to be conducted on a part-time basis—were the principal tools with which it enhanced its financial and political clout.

Profiting Twice Over

The JA has an overwhelming 80% share in the sales of fertilizer and 60% share in sales of pesticide and agricultural machinery. Nonetheless, because it is a cooperative it is largely exempt from the Antimonopoly Act and is free to form cartels.

Essential agricultural supplies cost twice as much in Japan as in the United States, even though they are made from the same materials. When a regional cooperative stopped purchasing fertilizer from JA Zen-Noh—responsible for procurement for the JA Group—it was able to cut its expenditures by 30%. One large-scale farm went to the trouble of importing fertilizer directly from South Korea.

Having to pay high costs for supplies means that farmers’ incomes decrease. It also means higher production costs and prices for agricultural goods and food products. The JA, however, profits twice over by charging for expensive supplies and produce. Sustaining high domestic prices requires higher tariffs, so safeguarding the interests of the JA comes at the expense of the interests of producers, consumers, and Japanese citizens as a whole.

Many politicians voiced their opposition to the hike in the consumption tax on the basis that it would be regressive and make food more expensive for the poor. These same politicians, though, have clamored to “protect Japanese agriculture” from free trade by maintaining high tariffs, despite the fact that this would have the same regressive effect of pushing up food prices.

In the United States and European Union, farmers are given direct payments by governments. This preserves the agricultural industry, while keeping product prices down for consumers. The same policy would ensure the health of Japanese agriculture. Lower prices would also generate greater demand, so there would be no need to reduce acreage. Part-time farmers would withdraw from the industry, enabling full-time farmers to increase the size of their land and benefit from economies of scale. Lower costs would also encourage exports, allowing the agricultural industry to grow.

If they received direct payments, farmers would not suffer from lower tariffs and prices. The JA would, however, take a major hit to its income. The loss of numerous part-time farmers would seriously reduce its membership numbers. For this reason, the JA has orchestrated a huge anti-TPP campaign; the free-trade agreement is not a problem for Japanese agriculture, though, but for the JA.

Following Koizumi’s Diet question, the JA’s handling of supplies and agricultural product sales became a discussion point in the government and LDP’s efforts to instigate reform. On November 11, the governmental Regulatory Reform Promotion Council’s working group on agriculture presented proposals that included a withdrawal from direct purchasing by JA Zen-Noh.

The JA and LDP lawmakers backed by the farm lobby vehemently opposed the proposals. Koizumi subsequently worked to reconcile conflicting interests in drafting the LDP’s Agricultural Competitiveness Strengthening Program, which offered a compromise to the JA in such areas as removing the time limit for organizational reform. On November 29, Prime Minister Abe Shinzō officially accepted Koizumi’s plan as government policy.

In its final form, the policy requires JA Zen-Noh to reform its various procurement and sales activities, such as by reducing the unnecessarily large variety of items purchased, which results in high supply prices. It must also produce and publish annual plans with numerical targets to be periodically checked by MAFF. In other words, the JA has been given a chance to reform itself. The Regulatory Reform Promotion Council’s recommendations of potentially establishing a second Zen-Noh and overhauling the banking division have been dropped entirely.

For years, politicians have ignored the contradictions at the heart of the JA. Fixed ideas will be difficult to dislodge, but the government’s new policy is not the final word on agricultural reform. The 2015 amendment of the Agricultural Cooperatives Act requires discussion of whether further reform is necessary five years later. I will watch with interest to see how far Koizumu Shinjirō can go in challenging what is postwar Japan’s largest pressure group.Recommendations of the Regulatory Reform Promotion Council’s Working Group on Agriculture

JA Zen-Noh Reform

- Withdraw from sales of agricultural supplies and focus on supporting farmers through price negotiations with manufacturers and sharing of information within one year.

- Abolish the current consignment sales system for agricultural products and commit to purchasing all products within one year.

- If there is no progress on reform, the government will promote the establishment of new organizations, such as a “second Zen-Noh” for the benefit of producers.

Banking Division Reform

- Halve the number of regional cooperatives operating financial businesses over the next three years, such as by transferring this business to Nōrinchūkin Bank.

Recommendations of the Government’s Agricultural Competitiveness Strengthening Program

JA Zen-Noh Reform

- Downsize the materials purchasing division into an organization that can negotiate more effectively with manufacturers.

- Switch from the current consignment sales system for agricultural products to a commitment to purchasing all products.

- (Neither of the above includes the one-year deadline recommended by the Regulatory Reform Promotion Council’s working group on agriculture).

- Produce annual plans to achieve reform results within five years.

Banking Division Reform

- (Not mentioned.)