A Mixed Grade for Japan’s New Tax Reform Plan

Economy- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

On December 8, 2016, the Liberal Democratic Party and the Kōmeitō announced their tax reform proposal for fiscal 2017 (April 2017 to March 2018). The two parties of the ruling coalition labeled it a first step toward raising the base level of Japan’s growth potential. It was disappointing that they ended up not undertaking a fundamental revision of the spousal deduction so as to promote women’s participation in the workforce—part of the work style reform initiative being pushed by Prime Minister Abe Shinzō’s administration. But some of the proposed changes merit positive assessment, such as the move to back up aggressive investments that will energize companies as they compete on the global stage, along with measures to address international tax evasion.

Elimination of Spousal Deduction Deferred

The lead item in the fiscal 2017 tax reform package was initially expected to be the elimination of the spousal deduction. This was to be the first major step in a comprehensive overhaul of the income tax system to be carried out over a period of several years.

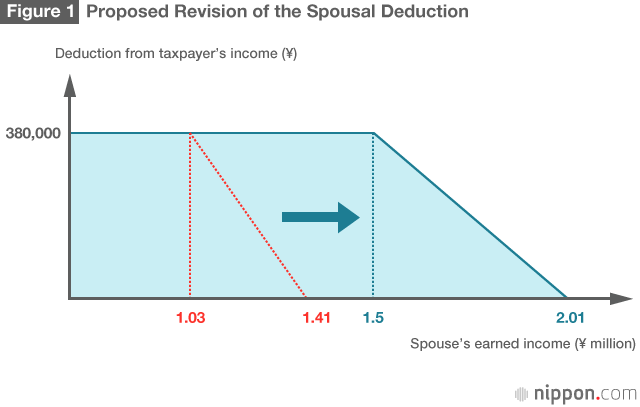

The existing spousal deduction allows taxpayers with spouses earning no more than ¥1.03 million a year to deduct ¥380,000 from their income for tax purposes, thereby lightening their tax burden. This arrangement has come under strong attack: People note that today it is more common for married couples both to work than for the wife to be a full-time homemaker. And the existence of a system that favors households with full-time homemakers is seen as discouraging women’s social advancement. People also point out that the system has the perverse effect of encouraging married women with part-time jobs to adjust their hours so as to hold their annual income below the ¥1.03 million threshold.

The deliberations on the 2017 tax reform proposal were thus expected to include consideration of replacing this spousal deduction with a couples’ deduction that would apply to all married people regardless of their spouses’ income levels.

Shortly after the deliberations of the LDP’s Research Commission on the Tax System got underway, however, prospects for the calling of a general election in the relatively near future came to the fore, partly in connection with hopes for positive developments from Russian President Vladimir Putin’s visit to Japan. And with this in mind, it was decided to halt consideration of any changes to the tax system that would increase the burden on individual taxpayers. As a result, the idea of eliminating the existing spousal deduction and instituting a new deduction for couples was taken off the table without a concrete proposal having been formulated.

Instead, the reform proposal calls for an increase from ¥1.03 million to ¥1.5 million in the cap on spouses’ earnings, with the amount of the ¥380,000 deduction gradually declining for taxpayers with annual earned income above ¥11.2 million, falling to zero if they earn ¥12.2 million or more. Instead of being eliminated, the spousal deduction is to have its scope extended. My frank assessment is that the income tax reform initiative fell flat right at the outset.

The real problem is that the discussion of eliminating the spousal deduction was dropped without even looking at other options, such as adoption of a deduction for married couples. According to my own calculations, if adopted on a revenue-neutral basis (meaning no net change in total tax revenues), the couples’ deduction would need to be limited to those with annual incomes of ¥8 million or less, but it would not affect over 70% of households, including most younger people, those with low incomes, and single people. The households that would end up paying more taxes would be limited to those with incomes topping ¥8 million where the wife is a full-time homemaker, which account for less than 10 % of the total. A greater number of households—those in the middle-income range—would see their tax burden lightened.

And if the new tax break for couples were set up not as a deduction but as a tax credit, as was proposed by the government’s Tax Commission, the lion’s share of those in the middle-income group—those with annual incomes of ¥3 million to ¥8 million—would see their tax payments decline. It is unfortunate that the LDP research commission failed even to discuss possible revisions based on objective figures like these. We cannot expect progress in deliberations on a major overhaul of the income tax system if those involved neglect efforts to set forth concrete options.

Unifying the Tax Rates on Beer

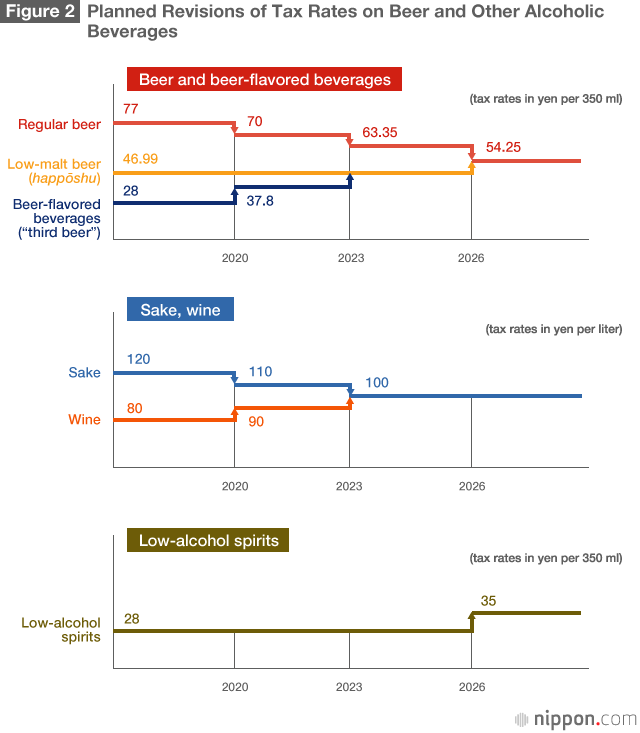

The present system of beer taxes applies different rates to three categories of beer and beer-flavored beverages, classified according to the percentage of malt they contain and differences of ingredients and manufacturing processes. A 350 milliliter can of regular beer is taxed at ¥77, but for low-malt beer (called happōshu in Japanese, with malt content of less than 25%) the rate is ¥47, and in the case of beer-flavored beverages (popularly called “third beer”) the rate is only ¥28. Under the proposed reform, the tax rates on all three categories are to be adjusted over a period of 10 years, at which point they will converge at ¥54 per 350 ml. In addition, the definition of beer under the tax code is to be broadened.

This may be considered a change for the better, reflecting the principle that similar types of alcoholic beverages should be taxed at the same rate.

Some have suggested that this reform is harsh on consumers who want to drink the cheapest beer they can and that it negates the efforts that brewers have made to meet the demand for such products. It is true that brewers deserve credit for some of the techniques they have developed to produce no-malt beverages with beer flavor. But some of their products are made simply by reducing the malt content without significantly changing the brewing method or by adding spirits to low-malt beer. So we cannot say that all the lightly taxed beers and quasi-beers are the product of positive corporate efforts.

With this unification of tax rates, the companies in Japan’s brewing industry that have been striving to come up with new products in the lower-taxed categories of beer and quasi-beer can shift their energies to the development of products aimed at assuring their survival in the face of international competition. And by offering good-tasting beer at low prices, the industry can benefit consumers while earning profits for itself.

Encouraging Investment and Dealing with Cross-Border Tax Evasion

Another positive element of the tax reform plan is its provision of additional flexibility for corporate reorganization in the face of global competition.

The reforms include a provision for the deferral of taxation on spinoffs—divestitures of corporate divisions or subsidiaries, with shareholders receiving stocks in the resulting new company. Spinning off non-core businesses allows executives to devote all their attention to their company’s core business. Meanwhile, the spun-off organization can make decisions more quickly and flexibly, and its management and employees should feel more motivated. In addition, spinning off operations can highlight corporate value that was previously not readily visible.

It has been shown in the United States that spinoffs are highly effective in enhancing corporate value. One recent example is the divestiture by eBay, a major e-commerce corporation, of its subsidiary PayPal; after this move the total value of the two companies was higher than that of the company prior to divestiture.

Over the past 10 years Japan took steps to reform corporate taxation by expanding the tax base while reducing the corporate tax rate. Now that this process has been basically completed, it is encouraging to see the tax reform planners turning to moves like the facilitation of spinoffs.

Another noteworthy point is the decision to include high-value-added services using artificial intelligence among the items eligible for the tax breaks applied to research and development. In this way the tax system will support the development of new businesses to keep Japan from missing out on the quaternary-sector revolution, which involves tapping advances in fields like the Internet of things and artificial intelligence.

The reform plan also allows for cumulative savings by individuals under the NISA scheme of tax-exempt small investments (NISA, short for Nippon Individual Savings Accounts, takes its name from Britain’s ISA, or individual savings account, system). The new option aims to promote regular accumulation of diversified investment products. Though small in scale, with a cap of ¥400,000 on annual investments, it is a welcome addition to the options for small investors, which also include defined-contribution pension plans for individuals. But NISA investments are currently limited mainly to stocks and investment trusts (mutual funds); the scope of permitted investment vehicles should probably be broadened.

A final point that merits favorable mention is the establishment of effective arrangements to counter tax evasion while continuing to support the healthy development of overseas operations by Japanese corporations. The Group of 20 leading industrial nations commissioned the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development to conduct a Base Erosion and Profit Shifting project to consider measures against tax evasion. The BEPS project produced its final report in 2015, and countries are now taking steps to implement its proposals. As part of its annual tax reform process, Japan has been taking steps in line with the BEPS principle that profits are to be taxed where economic activities occur and where value is created.

The tax reform plan for 2017 calls for revision of the provisions to deal with use of tax havens with the adoption of a system to consider the risk of tax evasion not on the basis of the explicit tax burden borne by overseas subsidiaries, but rather under a framework that better grasps the specific activities being conducted by each subsidiary (as indicated by types of income, for example). The provisions, which are designed not to require excessive paperwork from reporting corporations, are part of the overall campaign against international tax evasion.

(Originally published in Japanese on December 26, 2016. Banner photo: Miyazawa Yōichi [right], chairman of the LDP’s Research Commission on the Tax System, speaks with Motegi Toshimitsu, chairman of the party’s Policy Research Council, during a general meeting of the commission at LDP headquarters in Tokyo on November 21, 2016. © Jiji)