Five Years Later: Inflation Target Remains Elusive for BOJ Governor Kuroda Haruhiko

Economy- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

The Lessons of Massive Monetary Easing

Nearly five years have gone by since Bank of Japan governor Kuroda Haruhiko unleashed his unorthodox monetary easing policy. In 2013 the central bank set a target of achieving a 2% consumer price increase, implementing massive easing and a policy of negative interest rates, but as of December 2017 consumer prices (excluding those for fresh foods and energy) had increased by just 0.3% year on year, and the economy remains mired in deflation. But over half a decade of monetary easing, we learned several new things about how deflation occurs, and actions needed to overcome deflation have become clearer. Here I will discuss prices from the viewpoint of companies’ price-setting behavior.

Price Rigidity Hampers Escape from Deflation

Over the five years of the Bank of Japan’s massive monetary easing policy, I have been asked many times about the key to exiting from deflation. Many people believed that deflation, being caused by slack demand, could be overcome by demand-stimulating measures. They thought that the issue was whether loosening of monetary policy could sufficiently stimulate demand. But demand is not determined solely by prices—supply side factors, that is, the behavior of those who decide prices, are an additional element. It’s true that demand was weak at the time, but I believed that price-setting behavior was a far more serious problem. That kind of thinking made me an outlier at the time, but nowadays many policymakers, including BOJ officials, share my opinion.

Changes in the Philips curve focused my attention on the supply side. There is an inverse relationship between the rate of consumer price increases and the unemployment rate. When the unemployment rate goes down (or up), the consumer price increase rate trends in the opposite direction; this is the Philips curve. In Japan too, there used to be a negative correlation between prices and the unemployment rate, but this relationship became very weak after 2000: Despite changes in the unemployment rate, prices hardly budged. After the global financial crisis of 2008, demand did weaken and the unemployment rate surged, but prices remained low thereafter. In the five years since massive monetary easing, the opposite has occurred: Although the unemployment rate dipped to almost under 3%, prices have not risen.

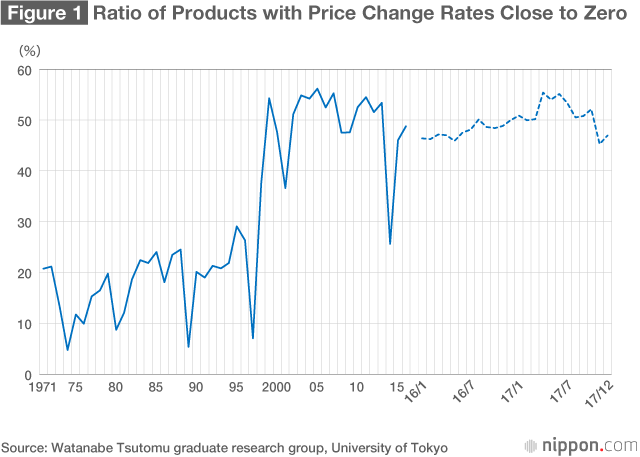

Price rigidity is behind this sluggish reaction. The consumer price index is composed of a basket of 600 items, shampoo or hair tonic, for example, that the typical consumer buys. After calculating the rate of change in the prices of each product compared to the previous year, the overall ratio of products for which consumption outlays have remained close to zero is worked out. (See Figure 1.)

Since items whose price changes have remained near zero are price-rigid items, working out the ratio of those items to the overall goods basket serves as a price rigidity indicator. Price rigidity began rising at the end of the 1990s, with nearly 50% of prices showing near-zero change. This situation has persisted even after the radical monetary easing policies adopted by the central bank in April 2013. Since mid-2017, the ratio of near-zero prices has been falling, but improvement is only gradual; even now, nearly half of the items in the basket are at near-zero levels.

Another reason for price rigidity is the drop in the trending inflation rate. In countries where the trending inflation rate is high, if one company holds prices back, its prices will be too low compared to those of its rivals and it will lose money. Accordingly, companies in those countries don’t keep prices at constant levels; instead, they frequently raise their prices. But in a country like Japan, where trending inflation is near zero, companies don’t lose money if they keep deferring price increases, so many of them choose this option. If the reason for this behavior is price rigidity, the rigidity will automatically disappear if trending inflation returns to normal.

But in Japan there’s another reason for price rigidity. According to an international comparison using price data for items in eight industrialized countries, including Japan and the United States, which I carried out with others, price rigidity in Japan is much higher than in the United States and remains high even after adjustment because Japan’s trending inflation is low.

Deferred Pricing Prevalent

What is causing Japan’s price rigidity? Calculating per item price increase rates and estimating maximum frequency distribution, Japan stands at zero while the United States is the mean; the level in many countries is 2% to 3%. This trend does not change even when adjusted for the impact of trending inflation. In other words, companies in the United States and elsewhere raise their prices by 2% or 3% every year, which is the default setting. Such companies are a majority in those economies, but in Japan the default is deferred prices, and that difference is what leads to price rigidity.

As deflation became entrenched in Japan starting around 1995, consumers came to expect deferred pricing as a matter of course and began rejecting even the smallest price increases. With consumers behaving this way, companies ran the risk of losing a large pool of customers if they raised prices, so they began deferring hikes even if their costs increased somewhat.

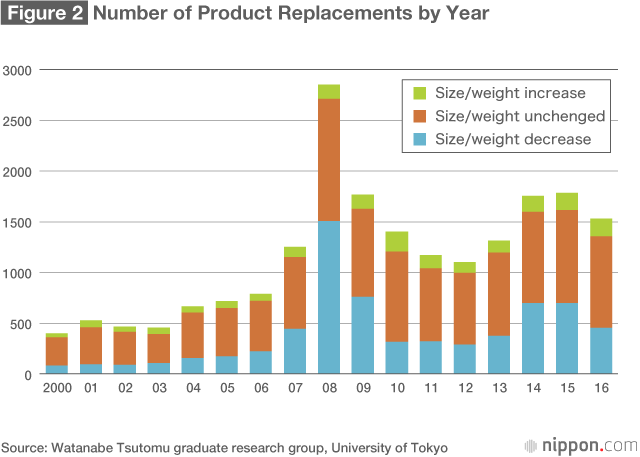

The practice of deferred price hikes has led to the warped phenomenon of shrinking packages. Last year, a hashtag meaning “Aren’t we getting less food for our money, Japan?” started trending on social media, and the blogosphere was soon filled with accounts of products whose prices had remained the same, but for smaller portions or reduced package weights. That is a de facto price increase. Figure 2 tracks the number of products whose size changed when the product was revamped.

De facto price increases shot up in 2008 when prices for imported grain and energy rose. Deferred pricing became commonplace, and since companies could not pass on their cost increases to consumers, they chose to make do by shrinking unit volume. Given that companies viewed deferred price hikes as an inescapable restriction, the end result of observing that limitation was smaller packages.

Package shrinkage declined for a time after 2008 but the pace picked up again from 2013 to 2015. That period coincided with the central bank’s massive monetary easing strategy and a weaker yen. Companies unable to pass on cost increases for imported materials most likely resorted to making their packages smaller then. Although companies are having to pay more for labor, mainly as wages for their nonregular employees, many more of them are finding that they are stuck and not able to pass on their costs.

Hurdles to Overcoming Deflation

The biggest obstacle to overcoming deflation is changing the custom of deferred price hikes. This practice will not disappear of its own accord, so something needs to be done. In fact, as young people who have never known anything but deflation come of age and become the main actors in society, this approach could become even more entrenched. If companies try to find ways of operating under the deferred price stricture, Japan’s economy will lose even more vitality.

The root cause of deferred prices is a “the cheaper, the better” mindset among consumers. Hiking prices to make a killing is out of the question, but raising prices to compensate for higher costs is a legitimate, fair business practice. Consumers go too far in refusing to accept any price increases at all, which distorts business activity. Consumers are also workers and should not forget that worsening labor conditions could negatively affect them if the practice of deferred price hikes continues.

Enterprises, meanwhile, should try to make their case with consumers as to why they need to pass prices on. In autumn 2017, Yamato Transport and other parcel delivery firms raised their prices. They explained that they had to do so due to a driver shortage and the consequent need to pay higher wages. Consumers were fine with this, and the move was successful, as they understood the need to raise prices to reduce the burden on front-line workers. But other companies are not so upfront. Stuck with the need to pass price increases on, they resort instead to downsizing product packages, and consumers end up in effect paying more. The key to ending deflation is returning to a healthy understanding of what constitutes a fair price.

(Originally published in Japanese on February 6, 2018. Banner photo: A supermarket placard announcing that prices would remain unchanged in the wake of a consumption tax increase. Taken on April 1, 2014, at the Kiba branch of the Itō-Yōkadō supermarket in Kōtō, Tokyo. © Jiji.)