Leaving the Iran Nuclear Deal: The Significance of Trump’s Decision for Japan

Politics- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

On May 8, 2018, US President Donald Trump announced he would pull the United States out of the nuclear deal with Iran, a decision carrying significant ramifications for the fate of the hard-won multilateral agreement. In 2002 the realization that Iran was working to build a nuclear bomb prompted rounds of frantic talks and the imposition of strict sanctions by the United Nations, United States, and European Union. In 2013, Hassan Rouhani became the Iranian president with his pledge to remove the sanctions, and after two years of talks an agreement in 2015was reached that effectively put the brakes on the country’s decade-long nuclear program. Under the deal Iran was subject to strict inspections by the International Atomic Energy Agency, who verified whether the terms of the deal were being met. Although most observers believed the agreement was functioning well, Trump abandoned the deal and expressed his intention to impose on Iran “the highest level of economic sanctions.”

Two Opposing Views of the Iran Nuclear Deal

To understand Trump’s decision, it is important to recognize that there are two diametrically opposed schools of thought in the United States on the Iranian nuclear deal. Trump’s predecessor Barack Obama regarded the development of nuclear weapons by Iran as the single biggest threat for his effort of nuclear nonproliferation and chose to deal with it with a two-pronged stance. While aiming to limit Iran’s ability to develop nuclear weapons and imposing IAEA inspections to ensure certain “safeguards,” he also recognized Iran’s right to peaceful use of nuclear energy and did not push to include provisions barring Iran from actions permitted to other countries like missile development and weapons exports. In other words, President Obama dealt with Iran as a normal country.

President Trump, on the other hand, regards Iran as a hostile state and a major cause of instability in the Middle East. He sees the existing nuclear deal as highly unsatisfactory and aims not merely to prevent Iran from acquiring nuclear weapons, but to completely dismantle its nuclear industry by enforcing a “zero enrichment” policy. He also aims to curb Iranian involvement in the conflicts in Syria and Yemen, and to put a stop to its missile development program. One way of understanding the president’s policy is to see it as a strategy of using the highest level of economic sanctions to strip Iran of its strength as a regional power.

Obama’s policy approach promised to deliver both political and economic benefits and was supported by other leading powers, including European allies as well as China and Russia. Under the agreement Iran would be allowed back into the international community and could resume oil exports, while at the same time other nations would gain access to its markets of some 80 million people. This is not to say, however, that the picture was altogether rosy. From the viewpoint of the United States and Europe, Iran’s involvement in the conflicts in Syria and Yemen was an undesirable development. Not only did Western powers staunchly refuse to recognize the legitimacy of Syria’s Assad regime, there was a risk of further heightened tensions with Saudi Arabia, which is fighting the Houthis armed movement in Yemen. The United States also regarded Iran’s missile program with disapproval for the risk it posed not only to Israel but to the overall balance of power in the Middle East, a point that caused further deterioration in the already antagonistic relations that had existed since 1979.

However, Trump’s treatment of Iran as an enemy state runs counter to the interests of European powers that have developed beneficial economic relations with Iran as well as China’s intentions of incorporating the country into its One Belt, One Road initiative. Russia also laments the hardline stance against a fellow strategic ally of the Assad regime in Syria. The agreement to stop Iran developing nuclear weapons—the largest common factor uniting Europe, China, and Russia—was functioning well up to Trump pulling out, and if the deal collapses now these countries will have to accept serious economic and strategic losses. There is also a risk that the deal’s failure will result in Iran developing nuclear weapons—something that no country wants to see happen.

The North Korea Effect

Trump has had plenty of opportunities to abandon the deal when deadlines for extending sanctions relief came up last October and again in January this year. This raises the question of why he has waited until now. One reason is that the president has finally appointed a team of trusted confidants to key positions to carry forward his own policies and strategy ideas. Until recently, many in the administration were strongly opposed to the idea of abandoning the deal and insisted that problems should be resolved by diplomatic means. This included former Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, former presidential advisor Herbert McMaster, and Secretary of Defense James Mattis. However, looking to surround himself with like-minded advisors Trump replaced Tillerson with former CIA director Mike Pompeo and McMaster with John Bolton, both well-known hawks. The president now has a team in place that makes it easier for him to push ahead with his ideas, and this is undoubtedly played a part in the timing.

Even more influential, though, is the dialogue with North Korea that has developed at such a dramatic pace since the beginning of this year. Until as recently as the end of 2017 North Korea was displaying open defiance and belligerence to the United States. It carried out its sixth nuclear test last September and was believed to be close to completing an intercontinental ballistic missile capable of reaching the mainland United States. Tensions between the two countries were at an all-time high.

However, the Trump administration with cooperation from China was able to tighten sanctions through the UN Security Council. By imposing a ban on imports of coal, iron ore, and oil it succeeded in forcing North Korea to the negotiating table. This diplomatic success with regard to its applying maximum pressure on the Kim Jong-un regime has worked to embolden the administration.

In truth, North Korea too has worked strategically to create the mood for dialogue and has successfully maneuvered the United States into a more conciliatory position. But from the perspective of Trump and its backers, the situation is irrefutable proof that strong sanctions produce an advantageous position from which to bargain, making it more likely for recalcitrant states to swallow American demands. It is fair to say that the success with North Korea was an important factor in the administration’s decision to leave the nuclear deal with Iran.

The Impact of Leaving

The decision to quit the deal is likely to have a multitude of repercussions. First, it has further deepened the political divide in American society. As I have already noted, opinion on the Iran agreement is split into two fundamentally opposed camps. While some American Jews and pro-Israeli evangelicals have applauded the decision, most Middle East experts and specialists in US-Europe relations have been strongly critical of the decision. Their concern is that America’s unilateral withdrawal from the agreement despite Iran keeping its end of the deal signals a wider American disengagement from the international community.

Of course, this is not the first time that the Trump administration has stirred up controversy that has divided society. But unlike the previous decisions to withdraw from the Paris Climate Agreement and the Trans-Pacific Partnership, which had yet to meet expectations, Trump’s recent decision showed the president pulling the plug on an agreement even though it was proven and functioning well to prevent Iran’s action.

Second, the gulf in US-Europe relations has now become unbridgeable. Just before President Trump announced his decision to withdraw from the deal, French President Emmanuel Macron, German Chancellor Angela Merkel, and British Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson all visited Washington in short succession, with Macron going so far as to include harsh criticisms of Trump’s proposed withdrawal in his address to Congress. But the president brushed aside these attempts to change his mind.

Also, the decision to re-impose sanctions is widely expected to mean secondary sanctions on European firms that have close economic ties with Iran, something that is likely to result in serious economic pain for these companies. The EU has reinstated its 1996 “blocking statute” stating that US and other foreign laws have no jurisdiction in the commonwealth and plans to take measures to compensate European companies that are adversely affected. But this is unlikely to be enough to counter the impact of secondary sanctions altogether.

It is unlikely, though, that the move to leave the nuclear deal will have a significant impact on conditions in the Middle East right away. Iran will no doubt suffer an economic shock as a result of the unilateral American decision, but it is important to remember that President Trump’s announcement does not mean the end of the deal altogether—merely that the United States has decided to leave it. The nuclear agreement and the United Nations Security Council Resolution 2231 that approved it will remain in force, at least in form.

If Iran is found to have infringed the terms of the agreement, though, it will still be forced to take responsibility for its actions. And the steps that Iran can take to protest the decision are relatively weak. Although it may restart uranium enrichment above the prescribed limits and reestablish centrifuges, it will not be able to quickly develop a nuclear weapon. Another factor is that any sudden progress toward developing nuclear weapons would increase tensions with Saudi Arabia and other neighboring countries, seriously destabilizing the region. In the worst-case scenario, it might lead to a “domino” effect with other nations racing to develop nuclear arms. Iran is therefore likely to respond in a relatively restrained manner.

There is also concern about the possible impact on the issue of North Korea’s nuclear program. Trump’s decision has created a precedent for the United States to leave a previously agreed on deal for its own reasons at any time, even if the conditions of the agreement are being met by other parties. In such circumstances it would be natural for the North Koreans to suspect that even if the US-North Korean summit on June 12 were to produce a deal, there is no guarantee that the agreement would be maintained on an ongoing basis.

On May 16, Kim Kye-gwan, First Vice Minister at the North Korean Foreign Ministry, described American unilateral demands as the “Libya model,” and hinted that he might not attend the summit as a result. Even if Iran was not mentioned by name, there can be little doubt that distrust and suspicion remain. Depending on how things develop, the results could well have a massive impact on Japan. In this sense, it is no exaggeration to say that the American decision to quit the Iran deal has caused serious instability in the international order.

A Limited Impact on Japan?

Finally, is it true to say that Trump’s decision is likely to have only a limited impact on Japan? Unlike European countries, South Korea, and India, Japanese companies have generally taken a cautious approach to investment and trading in Iran on the grounds that there is a real risk that the nuclear deal was not sustainable. Although there is likely to be some impact on petroleum imports and exports of automobile components, it is likely that Japan’s economic losses will be relatively mild compared to other countries.

There are also concerns about a possible pinch in the global oil supply if exports of crude oil from Iran come to a halt, but with Saudi Arabia and other producers expected to increase production, there have not so far been any major fluctuations in crude oil prices. Japanese companies tend to be sensitive to risk, and this often leads to a somewhat reactive “wait-and-see” policy. But on this occasion, companies’ cautiousness about plunging into the Iranian market may prove to have been sound business.

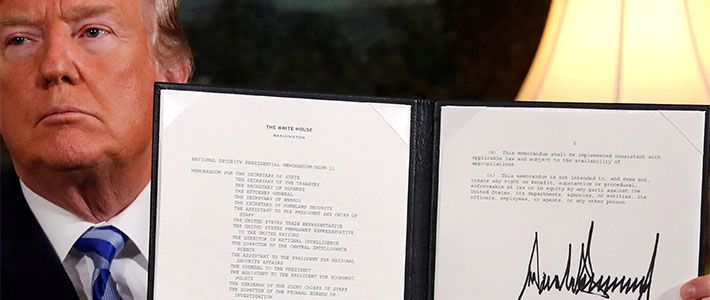

(Originally published in Japanese on May 25, 2018. Banner photo: Donald Trump in the White House on May 8, 2018, showing off the presidential order committing the United States to withdrawal from the Iran nuclear deal. © Reuters/Aflo)