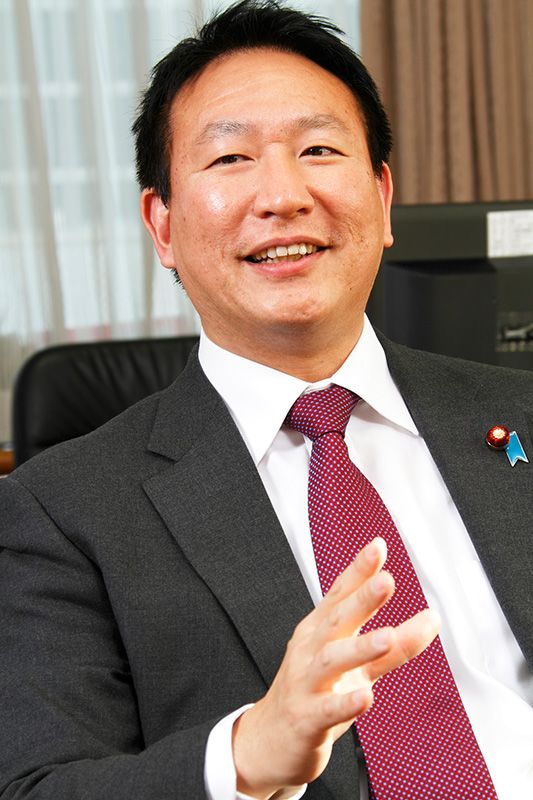

Kitagami Keirō, Vice Minister of Economy, Trade, and Industry

Politics- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Kitagami Keirō

Kitagami Keirō

Born in 1967. Member of the Democratic Party of Japan. After graduating with a degree in law from Kyoto University, joined the Ministry of Finance, where he worked in the tax bureau and Financial Services Agency, as assistant executive secretary to the prime minister, and as general affairs supervisor in the Iwate Prefecture department of general affairs. Elected to the House of Representatives in 2005. Was chosen as a Young Global Leader at the 2007 World Economic Forum Annual Meeting in Davos. In 2011, was appointed vice minister of economy, trade, and industry in the cabinet of Noda Yoshihiko.

After Fukushima

TAKENAKA HARUKATAYou assumed your post as vice minister of economy, trade, and industry in September 2011. Tell us about the kind of work your job involves.

KITAGAMI KEIRŌThe Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry faces a mountain of tasks at the moment. Dealing with the situation at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station and organizing recovery and rebuilding projects in Tōhoku, in particular support for small and medium-size enterprises . . . all of these come under our remit. We’re also responsible for preventing the hollowing out of the industrial sector as a result of the strong yen, for medium- and long-term energy policy, including reforming the way utility companies are run, and for dealing with the various issues surrounding restarting idle nuclear power plants. And then there are things like the Trans-Pacific Strategic Economic Partnership, or TPP, and COP17, the climate change conference held last November. I’m involved in all of these issues as vice minister.

TAKENAKAFor most people, of course, it’s the situation in Fukushima that is the biggest concern.

KITAGAMIAt the moment, we’ve successfully reached the second stage in the plan for dealing with the disaster, by achieving a cold shutdown of the affected reactors, and Prime Minister Noda Yoshihiko has issued an official announcement that the situation has been brought to a conclusion. Leaving aside the question of whether “conclusion” was really the best word to use in the circumstances, the essential thing was to bring about a stable situation in which there was no danger of a criticality incident reoccurring. This allows us to set about the long-term work of decommissioning the reactors where the accidents took place. The prime minister wanted to communicate to the Japanese people that we had succeeded in reaching the second stage in this process.

In December 2011 the government launched what it calls the Government and TEPCO Medium- to Long-term Countermeasures Meeting and published the Medium- and Long-term Roadmap for Decommissioning Reactor Units 1–4 at the TEPCO Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plants. The meetings are jointly chaired by Edano Yukio, minister for economy, trade, and industry, and Hosono Gōshi, state minister for nuclear accident settlement and prevention. I serve as deputy chair, along with Sonoda Yasuhiro of the cabinet office. I also act as head of the Research and Development Promotion Headquarters, which was set up under the supervision of the government-TEPCO countermeasures meetings. One of the jobs of the headquarters is to conduct research and development on the robot technology that will be necessary to remove the fuel from the reactors as we move forward with work on decommissioning and dismantling Fukushima Daiichi.

TAKENAKADo these efforts involve manufacturers and research laboratories from national universities?

KITAGAMIThe idea is for industry, government, and academia to work together on decommissioning the plant. This includes the National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology. But it isn’t easy!

I visited the institute recently to see the robots under development. One thing that gives the researchers headaches is that they don’t really know much about conditions at the site. This makes it impossible to decide what capabilities the robots will need. If there are perforations in the containment vessels, for example, they’ll need robots that can fill in the holes. Are there pools of water close to where the robots will operate? In that case, they’ll need robots that can function in water. The high radiation levels mean that no one can enter the site, making remote work necessary. But all kinds of factors have to be assessed: with all the rubble, will it be possible to move the robots wirelessly? Or will it be possible to connect a cord and move them that way? Of course, this is why it was so important to achieve a cold shutdown in order to ascertain the details of the situation on the ground.

Dealing with the Energy Crisis

TAKENAKAMost of the nuclear power stations around the country are idle after closing down for scheduled safety inspections. They can’t be started again without the permission of the local prefectural governors, but with public opinion firmly opposed to nuclear power, things have reached an impasse similar to the one in Okinawa over relocating the Futenma Marine Corps Air Station. With further electricity shortages forecast for summer 2012, how do you plan to deal with the situation?

KITAGAMIWe’ll do absolutely everything we can to avoid another crisis. This includes energy-saving measures, generating electricity at home, and increasing the amount of electricity generated through thermal power. It looks as though we’ll manage to get through the winter without any serious problems—but we need to realize that this has only been possible thanks to considerable sacrifices made by companies around the country.

But if demand surges again this summer, it might be necessary to restart some of the nuclear reactors—having first reassured the public that it is absolutely safe to do so. At the moment, public trust in the government is at a low point. We will invite expert opinions on safety from all the leading authorities in the field. This will include experts from the Agency for Natural Resources and Energy, the Nuclear and Industrial Safety Agency, and the Nuclear Safety Commission. We will also invite advice and opinions from the IAEA [International Atomic Energy Agency] and other international organizations. This evidence will then be presented to the people who live in the vicinity of the power stations. Hopefully it will be possible to reassure them that it’s safe to restart the plants. At the same time, I think we need to give serious consideration to making structural changes to the electric power sector. This includes possibly breaking up the utility companies’ regional monopolies and separating the rights to generate and transmit electricity.

TAKENAKAWith the IAEA involved, I’m sure it won’t be easy, but unless a steady supply of electricity can be guaranteed, there’s a risk that companies will shift production overseas, contributing to the hollowing out of Japan’s industrial sector. What ideas do you have for managing an electricity crisis in the final resort?

KITAGAMIPersonally, I believe that restarting nuclear power stations will be a crucial last line of defense against a national energy crisis. Of course we have asked the electricity companies to do everything they can to make up the deficit by thermal power generation, and we will leave no stone unturned in terms of looking for alternatives. But in a situation where there’s a real threat to Japanese industry, it will be crucial for the national government to take the lead in getting the power stations up and running again.

Politically speaking, obtaining the understanding of the local people is extremely important. But in a sense it’s really just a formality. Frankly, in a crisis situation it’s possible that the government would have to use state authority to prioritize a stable electricity supply. We are in careful, painstaking discussions with local people to try to avoid this kind of situation, doing everything we can to guarantee safety and bring reassurance.

The TPP and Japanese Diplomatic Strategy

TAKENAKAChanging tack slightly, I’d like to hear your views on the Trans-Pacific Partnership. One thing has struck me as strange in the debate on this issue: Why has the government come in for so much criticism from within its own party? So far all the discussion has been limited to whether Japan should take part in negotiations.

KITAGAMII agree with you—it is strange! The right to conduct negotiations on trade and commerce is one of the prerogatives of the executive, so really the government is under no obligation to canvass opinion or seek approval at all. But, as is the case on all important matters, if members of the party in the Diet see things differently, the government should take that into consideration and explain its position. This is true even if the matter in question happens to concern a normal part of executive powers or foreign policy. And so we duly went through a lengthy series of discussions on this subject too. Of the five senior figures at the ministry, I’m the one in charge of matters relating to the TPP. This means acting as the point of contact for party members who are noncommittal about the TPP or outright opposed to it. I suspect I was chosen for this position because I have a reputation for having a strong chin!

TAKENAKAIn connection with the TPP, there has been talk about the possibility of negotiations on individual FTAs with China and Korea.

KITAGAMIThe prime minister issued a declaration of interest in the TPP, a declaration that the Japanese media criticized as ambiguous. But the statement was enough to prompt a change in China’s stance. Suddenly, they were all in favor of an FTA with Japan. The Chinese seem to have formed the impression that Japan has plans to form an economic zone of cooperation with the United States. They were taken by surprise and started calling for greater economic cooperation within East Asia—between Japan and China, among Japan, China, and Korea, within the ASEAN+3 framework, and so on. Ironically, when Japan suggested a similar kind of arrangement previously, the response from the Chinese side was not quite as enthusiastic. It’s the same thing with the issue of trade restrictions on rare earths: Until recently, they would hardly give us the time of day, but their attitude has really softened since the prime minister’s announcement, even if the actual reality hasn’t changed much yet.

I’ve been saying for the past twenty years that the rise of China represents the biggest source of instability for Japanese foreign policy. In terms of Japan’s attempt to respond realistically to this threat, the TPP is an extremely important part of our foreign policy strategy. As Theodore Roosevelt said, “Speak softly and carry a big stick.” I think this ought to be our policy with regard to China. It’s important to be prepared, and to make it clear that we are prepared to take a tough stance too if necessary. It will be impossible for Japan to act alone on this. We need to lay the groundwork in cooperation with countries like the United States, Australia, and South Korea and work together to convey the message to China that it must do all it can to comply with the economic norms and rules of the developed world.

Military strength is also important. Since the DPJ took office, we have reduced the number of tanks in Hokkaidō and bolstered the strength of the Maritime Self-Defense Forces in the southwest. This also sends a clear message to China.

Three Reasons for the Chaotic State of Japanese Politics

TAKENAKAI’d like to widen the conversation and ask for your views on politics in Japan as a whole. I think it’s safe to say that the frequency with which Japan has gone through prime ministers since Koizumi Jun’ichirō resigned in 2006 is indicative of the chaos and confusion of Japanese politics. What do you think are the reasons for this?

KITAGAMII think there are three reasons. The first, you won’t be surprised to hear me say, is the House of Councillors. The upper house is simply too powerful. The second concerns problems with management and discipline within the political parties. The third reason, I think, stems from problems with public opinion, which is far too fickle and easily swayed by the media.

This is really more your area of expertise than mine, but there is a real problem with the upper house at the moment. If the party in government cannot command a majority in the House of Councillors, all its proposed legislation will end up being overturned there.

Another extremely important issue is the question of discipline and management within the parties. The response to the TPP question is a case in point. Unless we can come up with a system and culture in which the party membership basically conforms to the decisions of the party executive once a policy has been decided, and put a personnel system in place to bolster this culture, it will be very difficult to achieve any kind of stability in Japanese politics.

This is another reason why it is so important that we achieve a system in which the government and the ruling party are united and facing the same direction. I think it might be worth considering the idea of increasing the number of posts for senior vice ministers and vice ministers as a way of reducing discontent within the party. There is a famous line in the Chinese Classic of Rites that says, “In idleness, a man will do ill.” We tend to get up to no good when we have too much time on our hands. It might have been better if we had a system in place to provide opportunities for discontented elements within the party to work on the manifesto. At least we should give them some kind of job to do to keep them busy.

There were also problems with the way the party was managed under the previous prime minister, Kan Naoto [2010–11]. Some of the appointments that were made were hardly conducive to harmony and unity within the party. The secretary general during the 2010 election in which our party was defeated was then appointed chief cabinet secretary, for example. The person in question, Edano Yukio, is now minister for economy, trade, and industry. There is no problem with him individually—but the way the appointment was made, you couldn’t really blame people for thinking: “Wait a minute, what’s going on here?”

In terms of the procedures for deciding policy, the basic idea is that after the issues have been debated within the party, the chair of the policy research committee presents the membership’s views and a decision is taken at a meeting with the party leader and secretary general. But the decision-making framework within the DPJ is not yet as mature as the system in the LDP, for example, which has been around for much longer. The decision-making process is still a little vague within the DPJ and it is not always clear where responsibility lies. There is a tendency for people to put off decisions, and the debates sometimes go on forever.

The third reason I gave concerns problems with public opinion and voter expectations. Let’s face it: since the bubble economy came to an end, the simple fact is that whichever party is in power, politics is going to be mostly a matter of addressing unpleasant issues and pushing through unpopular legislation. It would be nice if the public would understand this and be more realistic in its expectations. Even when there is broad understanding of the need for reforms that will inevitably involve elements of pain, there tends to be fierce opposition when it comes down to the details. The proposed consumption tax hike is the most obvious example of this. There are just two policies on which there is no public opposition: civil service reforms and reform of politics. But even on these issues it would be helpful if voters would analyze the situation more coolly and understand the realistic limits to the kind of reforms we can carry out and the concrete results they will achieve in terms of public finances.

There are also major problems with the mass media. The French philosopher Alain once said something to the effect that the ideal occupation is one where you can control everything yourself. He thought craftsmen were happy in this respect. But politicians in Japan today are not in control of anything. It’s an extremely stressful job. Sometimes the media carry stories that are quite at odds with the facts. I complained once to someone that the media was carrying a story that wasn’t true. He just gave me a knowing look and said, “Listen, Kitagami, if the media says it’s the truth, there’s nothing you can do about it.” Unless we change the situation in which the politicians are at mercy of the media, there’s not much chance that politicians will be able to demonstrate real leadership.

Regaining the Public Trust

TAKENAKADespite what you say, do you have any aspirations to become prime minister yourself one day?

KITAGAMII really couldn’t say—even getting through the next election is looking quite difficult at the moment! Right now the DPJ is widely seen as a lying and incompetent party. Overturning that reputation will not be easy.

The only thing that interests me is a Japan that remains a great power in the world. The idea of saving up a nice little pension and retiring quietly, everyone relaxing and sitting around drinking beer and watching baseball on TV, doesn’t appeal to me at all. I want to help create a Japan that aspires to reach up to its full height and compete for the national interest in the wider world. In those circumstances, there might be some attraction to being prime minister. In politics the most important thing is opportunity and timing. Nothing you say or do will make a difference if it is not your moment.

TAKENAKAIf opportunity called and you did wind up as prime minister, what kind of policies would you prioritize?

KITAGAMIOne idea I have is to introduce compulsory classes on “great persons of history.”

The classes would be for elementary school students. Teachers would talk with passion and conviction about some of the most impressive individuals from Japanese history. Or people who are still alive and active today, for that matter. The baseball player Ichirō would be a good example. He was farmed out not long after he turned pro, but has risen to become one of the leading players in the world. Someone asked him once: What’s the most important thing in baseball? His answer was: treating your equipment with care. I think this attitude typifies a certain kind of Japanese aesthetic. I want to pass a sense of this on to our children.

What I like about this idea is that it would provide a good way of giving children role models. Having someone to look up to is crucial to all successful education. Children should be inspired to follow the example of these successful people in their own lives. What is more, I think that teaching children about the outstanding individuals that Japan has produced will help to inspire a sense of patriotism. This kills two birds with one stone. This kind of education would not just instill a healthy sense of patriotism but also a sense of responsibility in individual citizens that would help Japan to compete and flourish in the international community.

TAKENAKATalking of learning from historical figures, is there any particular postwar prime minister that you personally admire?

KITAGAMIKishi Nobusuke [1957–60]. I admire the way he managed to push through the revision to the Japan-US Security Treaty during his short but productive time in office. He did everything he could to make the distorted relationship between Japan and the United States more equal. He sacrificed his political career to achieve this, and I think he deserves a lot of respect for that.

(Translated from an interview in Japanese. Photographs by Takashima Hiroyuki.)