The Direction of Contemporary Japanese Politics

The Pressures of Change: The Office of Prime Minister in the United Kingdom and Japan

Politics- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Today, the environment surrounding the role of the prime minister (or what we might call “prime-ministership”) is undergoing dramatic changes in both Japan and the United Kingdom. More attention than ever before is paid to the prime minister as an individual, and the expectations and pressures of the job have increased rapidly. In this essay, I want to examine from four perspectives the contemporary demands that prime ministers in both countries are facing in common, and discuss the effects that these pressures are having on the evolving way in which the prime-ministership operates. To this end, I will look at the efforts being made in both countries to bolster the institutions in place for providing advisors to the prime minister. In particular, I pay close attention to the situation in Japan. I will also discuss the issues arising from the short and unstable political cycle faced by Japanese prime ministers—one of the decisive differences between the two political systems.

A Changing Environment

The environment in which the prime minister operates has changed in remarkably diverse ways. The job and the context in which it is done have been evolving gradually over the past 40 years. In this essay, I want to look at these changes from four perspectives: changes to the media, changes to election campaigning, the increase in summit meetings, and the need for the core government offices to set policy and decide on the overall direction of government.

The Changing Media Climate

It is a quarter of a century since television started to play a major role in Japanese political reporting, and twenty years since the 1993 general election in which TV played a more important role than ever before. Political coverage on TV inevitably focuses on the individual, and demands that individual politicians (and the prime minister in particular) take responsibility for the political problems faced by the government.

Japan has not yet reached the situation that now prevails in Europe and North America, where 24-hour rolling news demands that the government operate around the clock. But the advent of social media in recent years has further accelerated the tendency for people to expect an instant response to events as they unfold. Within this changing media environment, the government is required to communicate its message speedily and consistently—and increasingly, it is the prime minister who bears the main responsibility.

Changing Election Campaigns

Changes in the way election campaigns are run have also focused attention on the prime minister and other party leaders. In Britain, there is a long tradition of strong, well-established political parties and the ideological dividing lines between the parties are relatively clear. Until recently, the roles of the prime minister and other party leaders were therefore secondary to the roles of the parties themselves. In the Japanese system, too, the prime minister and rival leaders traditionally played a secondary role in election campaigns. Here, personal votes were more important and “supporters’ groups” backing individual candidates traditionally played a central role.

Today, however, the situation is different. The lines between the parties are no longer as obvious as they used to be, and it is no longer possible to win a majority through personal votes alone. In this context, people—particularly politicians and candidates—tend to become intensely conscious of the image of the party leader.(*1) In Japan, this tendency has become particularly pronounced since 1994, when the voting system for electing members to the House of Representatives changed. Since the second half of the 1990s, public support has also become a decisive factor in internal party elections to select the president of the Liberal Democratic Party.(*2) In the policy-making process in both Britain and Japan, the prime minister is the actor most exposed to public opinion—or, to put it another way, the individual whose position depends more than anyone else’s on public support.

More (and More Important) Summit Meetings

A third reason for the changes in the role of the prime minister in the policy-making process is the increase in the number of summit meetings and their growing importance. Foreign policy today takes place in a political climate quite different from the days when diplomacy was the responsibility of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the ambassadors around the world. Particularly since the advent of the Group of Six (then Group of Seven, now Group of Eight) meetings that began with the Rambouillet summit in 1975, the prime minister has been reassigned to the front lines of diplomacy.(*3) No longer can the prime minister hide in the shadows of foreign policy professionals.

Summit meetings are increasing the role and burden of the prime minister, which can be observed by looking at Noda Yoshihiko’s schedule in office.(*4) In the twelve-month period from December 2011, he traveled repeatedly overseas. After visiting China and India in December, he took part in the nuclear security summit in Seoul in March 2012. In April he was at the US-Japan summit in Washington. In May he attended the Pacific Islands Forum in Okinawa, followed by the G8 summit at Camp David and the Japan-China-South Korea summit in Beijing. June brought the G20 summit at Los Cabos, Mexico—a hectic schedule that was followed by September’s APEC summit in Vladivostok, the ASEM leaders conference in Vientiane, Laos, and the ASEAN leaders’ summit in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, both in November. In addition to these summits, information released by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs reveals that Noda took part in 46 telephone meetings with foreign leaders during the year.

Under incredible pressure from his own party and faced with an intractable “twisted Diet” at home, Noda was unable to give diplomacy as much time as it deserved, as was demonstrated dramatically at the G20 summit. As a result, even when he attended he was hardly a focus of major attention. But regardless of the realities of the situation at home, the prime minister is required to meet other leaders on a regular basis. To squander these opportunities can only be to the detriment of any country’s interests.

Strengthening the Core Government Offices

The final factor is the growing need for stronger core government offices. There needs to be a major rearrangement within the government to make it easier to coordinate, integrate and communicate messages relying on the authority of the prime minister. Why? One reason is that an increasing number of policy-making issues now require an all-government response. At the same time, sectionalism has won out in the bureaucracy and taken over from the traditional management principle in which the relevant cabinet minister would take charge of policy within his or her sphere of responsibility. As a result, the government is not in a position to make a satisfactory response.

Classic examples of this can be seen in industrial and agricultural policy, education and employment, and pensions. Developing a strategy to deal with Japan’s dwindling birthrate, for example, concerns many areas of policy-making: from long-term economic growth to employment, education, and social and family policy.

Additionally, political leaders tend to have a deep-seated distrust of the bureaucracy. Since the 1990s in Japan—and since the 1970s in Britain—there has been an observable lack of policy ideas coming from within the bureaucracy. This has been particularly striking in the area of economic policy. Political leaders’ distrust of the bureaucracy has only increased with time. The bureaucracy does make suggestions on political and policy decisions, but this has been insufficient for political leaders. The core government offices, headed by the prime minister, require policy ideas to supplement the bureaucracy as well as information and suggestions relating to political decisions. In some conditions there is a need for supervision of the bureaucracy.

In both Japan and the United Kingdom the prime minister is expected to play an increasingly prominent role. The changes that have taken place are irreversible.

The Prime Minister’s Role: “Presidential” or “Chairman” Model?

In the United Kingdom, there have for many years been two main approaches to the role of the prime minister. One approach sees the prime minister as being to coordinate the cabinet ministers who are responsible for implementing public policy through their ministries. The other view is that the prime minister is the leader in a top-down system. We can think of these two approaches as the “chairman model” and the “presidential model.”

In the case of the United Kingdom, neither of these views alone is sufficient to explain the reality of the prime minister’s role in recent years. In fact, prime ministers fitting both descriptions have alternated in office for the past several decades. Top-down “presidential style” Margaret Thatcher was followed by the consensual “chairman” approach of John Major. After him came Tony Blair, who was a classic top-down “presidential” prime minister; after him came Gordon Brown, who promised to be a consensual chairman-style prime minister but in fact behaved as a “presidential,” top-down leader. The current prime minister, David Cameron, seems to be regarded by most observers as more of a consensual, chairman-style prime minister.

These two views also apply to the situation in Japan. Article 65 of the Japanese Constitution states that: “Executive power shall be vested in the Cabinet.” This means that in Japan executive power is theoretically wielded collectively by the Cabinet—in this sense, the Japanese political system is quite different from a presidential system, in which executive power resides with a single individual. The various ministries are arranged under the authority of the cabinet, and each ministry has traditionally been responsible for setting policy within its own sphere. This is the principle of divided responsibility. The system is predicated on an understanding that each ministry has the initiative and autonomy to decide on policy within its own remit. In the British case, according to the chairman model, the expectation is that policy will not be decided according to the personal preferences of the prime minister. Instead, the prime minister is responsible for carrying out the policies set out by the party in its election manifesto. The prime minister’s main job is to steer the government and keep it on course.

By contrast, the top-down or presidential model envisages that the prime minister will personally decide the priorities and direction of the government, treating cabinet ministers as subordinates, and taking a leadership role by becoming directly involved in the policy-making process. The Japanese constitution leaves room for this type of prime minister. The constitution defines the prime minister as the “head” of the cabinet, with the right to appoint ministers of state and exercise control and supervision over the various administrative branches. Further (although this point is more controversial) the cabinet has the right to dissolve the Diet. As the most important individual decision-maker at cabinet meetings, the prime minister therefore has a key leadership role here too.

Particularly important is the prime minister’s right to appoint cabinet ministers. This is no mere ceremonial role. Indeed, it is this prerogative that symbolizes the position of the prime minister within the government. Furthermore, since Article 74 of the constitution requires all laws to be countersigned by the prime minister, no law or cabinet order can come into being without the consent of the prime minister. Regardless of the reality of the individuals who have actually held the office, it is therefore quite possible to interpret the present constitution as expecting the prime minister to exercise a considerable degree of executive leadership. This is true even without any of the administrative reforms discussed below.(*5)

There are thus two ways of looking at the role of the prime minister. But whichever view we take, the reality is that a prime minister today who is content to act as coordinator, leaving the bureaucracy to take the lead on important policies, will struggle to respond adequately to the demands of the new environment. Come election time the prime minister is in the most prominent position as the public face of his party and the embodiment of its manifesto. Once in office, the prime minster sets the government’s direction and must justify it constantly to the public through the media. Because of this, the reality is that it is now extremely difficult for any prime minister to avoid the more proactive role now expected of the job—regardless of the personal inclinations or preferences of the individual in question.

The Need for a System of Advisors

As we have seen, prime ministers in both Japan and the United Kingdom are being pressed to respond to a changing environment that affects the way they can do their job.

Choosing people who are suited to the challenges of this new environment is therefore essential. Although they may have been highly regarded by their peers at the time, it is hard to imagine men like the sickly Hatoyama Ichirō (prime minster December 1954–December 1956) or the tongue-tied Ōhira Masayoshi (December 1978–June 1980) as likely choices for the top job today. It is possible that this situation prevents people who might otherwise have been gifted political leaders from coming to the fore. But for better or for worse, the reality is that a prime minister today needs the ability to “connect” with people directly. This does, however, have potentially dangerous consequences for contemporary politics, as people can be reached simply by fostering hatred, rivalry and fear.

Having said this, the problem is not purely one of personality. The organizational infrastructure around the prime minister is also coming under increasing pressure to respond to the new environment. In the United Kingdom, work to reform the structure that supports the various roles of the prime minister began in the 1970s and 1980s, and took off dramatically during the Labour governments led by Tony Blair. The Prime Minister's Office, the Cabinet Office, and the Treasury began to act as the command center of government, superior to the other ministries. A new hierarchy was formed among the various ministries.(*6)

The number of special advisors has also increased dramatically to support the prime minister’s range of new roles. In 1995–6, when John Major was in office, there were 38 special advisors, 8 of them special advisors to the prime minister’s office. By 2000–1, under Tony Blair, these numbers had risen to 79 and 25 respectively; by 2004–5 they had risen again to 84 and 28. The current Conservative-Liberal coalition government was initially critical of Labour for hiring an “excessive” number of advisors, and reduced the number to 68 shortly after coming to office. Two years later, however, the number had increased to 84. Although the roles of the special advisors are open to criticism in a number of areas, and their roles remain ambiguous in some respects—particularly in regard to their relationship with public servants—they are nevertheless becoming indispensable to the smooth running of government in the United Kingdom.(*7)

Establishing a fuller system for assisting the prime minister is an urgent task in Japanese politics too. The system as it stands expanded gradually over the postwar period. In particular, the Cabinet Secretariat was strengthened as part of the reforms carried out under Prime Minister Nakasone Yasuhiro during the mid-1980s and Prime Minister Hashimoto Ryūtarō in the late 1990s. The Cabinet Office was also established during the latter reforms. At present, a maximum of five advisors can be appointed to help the prime minister. In addition, in recent years a number of people have been appointed to the legally ambiguous position of “advisor to the cabinet.” Under the second Abe cabinet, 11 people had been appointed to this position as of October 2013. Under the previous Democratic Party of Japan government, organizations including the cabinet ministers committee and the National Policy Unit were established, but these new organizations never reached the stage where they were able to function fully.

The first striking difference of the system in Japan and the one in place in the United Kingdom is that as a rule, the prime minister’s assistants and advisors are Diet members and government bureaucrats. For the Japanese prime minister, directing bureaucrats without drawing criticism from the highly autonomous offices of bureaucracy is a serious challenge. The problem is not so much that bureaucrats are insufficiently loyal to the prime minister. Rather, the differences between the politician’s and the bureaucrat’s perspectives mean that it is difficult for a bureaucrat to give the right kind of advice on political issues.

On the other hand, Diet members have their own issues with elections and promotions, and it is not easy for the prime minister to secure absolute loyalty from them. The prime minister needs advice and information from a political perspective, and therefore needs staff with good political instincts who can keep a low profile. One characteristic of politics in Japan is that the political influence of people from outside the Diet tends to be extremely limited. The prime minister’s chief secretary and advisors to the cabinet do provide assistance to a certain extent. But at present there is only one chief secretary in office, and advisors are not considered a full-time appointment. This makes it difficult for these individuals to become fully involved.

Second, the systems in place for assisting the prime minister in Japan are chiefly designed to help with fine-tuning policy. There is no adequate system in place to help the prime minister in other important areas: dealing with the media, assessing public opinion, working on foreign policy issues, evaluating new policy recommendations, and maintaining relationships with the ministries. All of these are too important to be left to the individual skills and political sense of the prime minister. Even in terms of setting policy, it is unfortunately not the case that important issues are routinely considered in the Cabinet Secretariat or the Cabinet Office. Instead, what tends to happen is that the core government offices centered on the prime minister push for a rapid response only after the problem has already developed to a certain extent. The result is that at present the core government offices tend to play a passive and reactive role.

Third, the expansion of the roles of the core government offices since the 1980s has coincided with the increasingly prominent position of the chief cabinet secretary. The chief cabinet secretary has historically performed a wide range of diverse roles: as the most senior moderator of policy within the core of government, the chief spokesperson responsible for making official statements on behalf of the cabinet, an intermediary between the cabinet and the ruling parliamentary party, and intelligence-gatherer within core government, and for practical purposes its chief crisis manager. It would not necessarily be an exaggeration to say that the success of a government depends just as much on the chief cabinet secretary as on the prime minister. As a result, it is clear that the burden on the chief cabinet secretary has become too great. The DPJ government establishment of the new position of Minister of State for National Policy in an attempt to divest some of the responsibility for policy coordination onto another cabinet minister, but this cannot be described as a total success. In order to improve the performance of the core government offices, partitioning the responsibilities currently borne by the chief cabinet minister and devolving them to a properly thought-out system is essential.

As we have seen, the organizational infrastructure for assisting and advising the Japanese prime minister has therefore been augmented with a view to providing a fuller mechanism for coordinating policy by using the bureaucracy. But there is still a need for more horizontal coordination between different departments within the core government. And as far as overall policy direction and intelligence-gathering are concerned, work to improve the system has barely begun. The Council on Economic and Fiscal Policy set up under Prime Minister Koizumi Jun’ichirō was an important attempt in this respect. But although the council was established within the Cabinet Office, in reality it was too dependent on the personal authority of Koizumi, and subsequent prime ministers have failed to make full use of its potential.

Of course, the development of a government centered on the prime minister brings with it a variety of problems. The systematic redundancy between core government and the bureaucratic apparatus, the excessive attention given to areas of policy in which the prime minister, chief cabinet secretary, or cabinet ministers happen to be personally interested, the tendency of these priorities to shift without warning, the group thinking that tends to results from the influence of aides, the increasing difficulty of maintaining control owing to the centralized government and greater of political advisors—all of these were seen both in the governments of Tony Blair (widely criticized as a “control freak”) and in the first Abe Shinzō government, which critics said marked the “collapse of the prime minister’s office” in Japan. The current Abe government is pushing a seemingly personal agenda with the support of his staff, owing to a lack of strong opposition from his and other parties.

Nevertheless, a system to assist the prime minister is probably unavoidable in order to respond to the needs of the age—in terms of mass media strategy and dealing with public opinion, assistance on foreign affairs, political advice and advice on policy ideas, intelligence gathering, and liaison between core government and the ministries. Indeed, it is possible to take the view that the current lack of a strong core government in Japan is causing serious problems, as seen in the chaos brought about by Hatoyama Yukio’s attempts to relocate the US Marine Corps Air Station in Futenma to a location outside Okinawa, thereby going against agreements between previous governments and the United States.

Short Political Cycle, Unstable Prime Minister

The fact is that despite the requirements of the times, the prime minister is still not always able to make his presence felt sufficiently. This is partly due to the shortness of the political cycle in Japan and, related to this, the instability of the prime minister’s position. This becomes clear if we compare the situation with the way things happen in the United Kingdom.(*8)

The expectation that the prime minister and party leader will be in position for a certain period of time is crucial if the prime minister is to secure the loyalty from cabinet ministers, bureaucrats, and members of the ruling party. The individuals involved in policy management need to see that the prime minister’s position is stable, if they are to regard him or her as an individual worth devoting themselves to faithfully loyally from the perspective of their own medium- and long-term career prospects. If there is no expectation that the prime minister will be in office for at least a certain period of time, it will be impossible to inspire a sense of loyalty. If ministers and the parliamentary party know that they can be successful in sabotage, there is no longer any need for them to carry out the prime minister’s intentions. Regardless of how much official authority the prime minister may have within the government or party, without a stable position it becomes impossible to exercise that authority.

Japan has had 31 prime ministers since the current constitution was promulgated in 1947. In the same period, Britain has had only 14. In other words, Britain has had less than half as many prime ministers as Japan—on average, each prime minister has therefore been in office for more than twice as long.(*9)

In the United Kingdom, changes of prime ministers tend to coincide with general elections—including when a party dumps its leader because they think he or she has no chance of winning. The votes to choose a party leader do not generate their own political cycle, and a prime minister’s term in office will continue for as long as he or she can continue to win (or reasonably expect to win) a general election.

In Japan, by contrast, prime ministers have resigned for all kinds of reasons. Particularly important is the frequency with which national elections and voting for party leaders take place. Because of Japan’s bicameral voting system, elections for the national legislature take place on average every 18 months, and as party leader the prime minister is forced to take responsibility for his party’s result in both houses. Although it may be only reasonable for the cabinet to resign if the party is defeated in elections for the lower House of Representatives, the prime minister in Japan has come under pressure from within his party to resign after a heavy defeat in the upper House of Councillors as well.

Another factor is that historically both the LDP and the DPJ have set their leaders’ terms of office at just two or three years, and until the DPJ changed its rules recently, both parties’ regulations stipulated that successor taking over partway through a term inherited his predecessor’s original term with its original expiry date. This can lead to some peculiar situation. When Hatoyama Yukio took over Ozawa Ichirō’s term, and then resigned partway through Ozawa’s original term as leader, for example, the result was that his successor Kan Naoto was obliged to fight for reelection just four months after becoming party leader.

If national elections happen too frequently, they lose some of their significance. There is also a risk that holding the voting for party leaders on a schedule unrelated to the national election timetable could end up negating the results of a national election. Naturally, the likelihood that a prime minister will soon be replaced tends to reduce his authority. This in turn affects unity within the ruling party.

Of course, the opposite problem arises if the prime minister continues in office too long. In this case, it becomes difficult to control his power, and the government becomes less answerable to the electorate. If we are to change the system to make the prime minister’s position more stable, therefore, we also need to provide alternative measures for limiting the prime minister’s authority. This might include increasing transparency and making more information available to voters to allow them to pass judgment on the government’s performance. Other options would be to give Diet committees more leeway to issue warnings on overall policy direction and to make fuller use of the bicameral system.

The way the system currently operates, under a “twisted Diet” in which control of the two houses is split between government and opposition parties, the House of Councillors can pass a motion of censure and by boycotting sessions, effectively has the ability to remove the prime minister and cabinet from office. This not only makes it difficult for the prime minister to exercise his authority, but also exacerbates the instability of the political system as a whole. Although the House of Representatives is theoretically superior and is responsible for appointing the prime minister, when it comes to dismissing the head of government both houses in effect have equal powers. The problem of imbalance is self-evident.

Compared to the political system in the United Kingdom, in Japan the political cycle is short-lived and unstable. This means that despite the frequency with which the country changes its prime ministers, at present the preferences of the electorate are not necessary reflected in the position of prime minister.

Conclusion

Today, the office of prime minister faces similar challenges in both Japan and the United Kingdom. In both countries, there is a need for leaders and a system of advisors who can help the prime minister to respond to the new needs of the age. The United Kingdom has made rapid progress in improving its advisory infrastructure since the Labour governments of Tony Blair. More recently, in Japan too there have been moves toward creating a core government focused on defining and refining policy. But particularly in Japan, the problem is not simply a lack of sufficient infrastructure to advise the prime minister. The difficulty goes beyond that. The less than ideal political cycle strips the prime minister of the necessary authority and deprives voters of choice and control.

The political environment today is quite different from the one that prevailed 20 years ago. The changes have had a particularly strong impact on the office of prime minister. The prime minister in both countries is being pressed to respond to these changes. The political system as a whole needs to come up with appropriate ways to guarantee and control the appropriate levels of power and authority for the office.

Addendum: This article was originally written in April 2013, soon after the December 2012 elections that saw the DPJ swept out of power and its political influence severely diminished. Since then, the party system in Japan has been going through major changes. When the LDP returned to power under Abe, the lack of a major opposition party served to relieve the political gridlock that had been affecting the Diet. This has resulted in a stable political cycle, but it also has potentially significant negative implications for the political system by depriving it of a key element for checking the party in power.

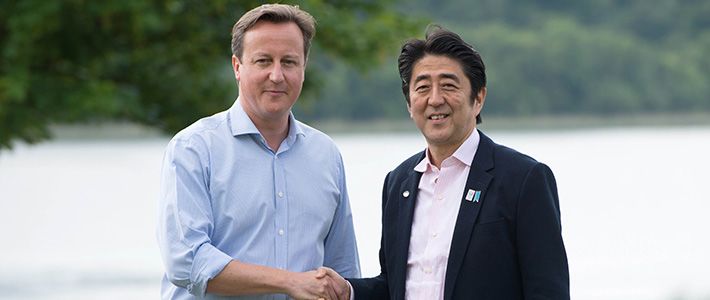

(Originally published in Japanese on November 1, 2013. English version revised on May 22, 2014. Title photo: British Prime Minister David Cameron welcomes Prime Minister Abe Shinzō to the G8 summit at Lough Erne in Northern Ireland on June 17, 2013. Photo by Bertrand Langlois/AFP/Jiji.)

(*1) ^ However, it is not necessarily clear whether the “images” of party leaders have a decisive effect on election results. Cf. Anthony King, “Do Leaders’ Personalities Really Matter?” and John Bartle and Ivor Crewe, “The Impact of Party Leaders in Britain: Strong Assumptions, Weak Evidence” in Leaders’ Personalities and the Outcomes of Democratic Elections, ed. Anthony King (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002).

(*2) ^ Takenaka Harukata, Shushō shihai: Nihon seiji no henbō (Prime Ministerial Control: The Changing Face of Japanese Politics), Chūō Kōron Shinsha, 2006.

(*3) ^ The summit at Château de Rambouillet in 1975, in which six countries took part, was the first G6 meeting. Canada joined the following year, and the summit was known as the G7 until Russia became a formal member at the 1998 Birmingham summit, after which the meetings were known as the G8.

(*4) ^ From the website of the Japanese Minister of Foreign Affairs, accessed April 14, 2013.

(*5) ^ Takayasu Kensuke, Shushō no kenryoku: Nichi-Ei hikaku kara miru seikentō no dainamizumu (The Power of Prime Ministers in Japan and Britain: Dynamics of Their Relationships with the Governing Party), Sōbunsha, 2009; Kensuke Takayasu, “Prime-ministerial Power in Japan: A Re-examination,” Japan Forum 17, no. 2 (2005).

(*6) ^ Takayasu Kensuke, “Giron, chōsei, kettei: sengo Eikoku ni okeru shisseifu chūsū no henyō,” (Discussion, Coordination and Decision-making: the Changing Core Executive in British Government), Kōkyō seisaku kenkyū, no.9 (2010).

(*7) ^ Oonagh Gay, “Special advisers,” House of Commons Library Standard Note, SN/PC/03813 (last updated: August 7, 2012), p. 14.

(*8) ^ For a more detailed comparison between political cycle in Japan and the United Kingdom, see the works cited below. Takayasu Kensuke, “Naze Nihon no shushō wa sugu ni kōtai suru no ka: mijikai seiji saikuru ni honrō sareru Nihon seiji,” (Why Do Japanese Prime Ministers Change So Often? The Dominant Effect of the Short Political Cycle in Japan), Sekai, November 2010; idem. “Giin naikakusei to seiji saikuru: Nichiei hikaku no shiza kara” (The Parliamentary System: A Comparison between Japan and the United Kingdom), Seikei Hōgaku, No. 73, 2010.

(*9) ^ Counting Harold Wilson and Abe Shinzō, who both served two separate terms during this period, twice.

politics Tony Blair Margaret Thatcher Hatoyama Yukio Abe Shinzō Nakasone Yasuhiro Hatoyama Ichiro Koizumi Jun'ichirō Ozawa Ichiro Hashimoto Ryutaro Democracy Ohira Masayoshi twisted Diet prime minister cabinet United Kingdom Takayasu Kensuke John Major Gordon Brown