A Tradition Ironed Out over the Years: The Cast-iron Creations of Okamaya

Economy- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

A Centuries-old Firm

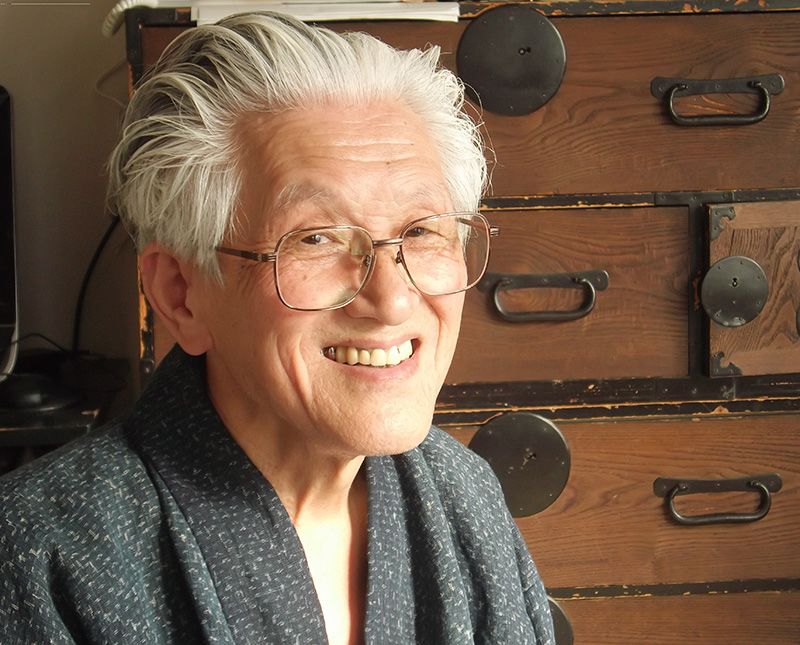

The traditional Japanese tea ceremony is about more than the tea itself. Equally, if not more, important are the utensils that play a part in the ceremony, including the cast-iron kettles used to boil the water. These kettles have been in use for around 350 years, starting in the Edo period (1603–1868). One firm that has been crafting these items all those years is Okamaya, based in Morioka, Iwate Prefecture (then known as the Nanbu Domain). Established in 1659, the firm today is led by 78-year-old Koizumi Nizaemon, the tenth person to be its head.

We visited Koizumi at his home, located a 20-minute walk from the Morioka train station, with a simple sign reading “Okamaya” hanging outside. His small workshop is a further 20 minutes away by car. He works side by side with his son, Koizumi Takehiro.

Because production of cast-iron kettles (tetsubin) and pots (kama) was centered in the Nanbu Domain, those items came to be known as nanbu-tetsubin and nanbu-kama. Koizumi Nizaemon explains more about the origins of iron production in the region:

The sign hanging outside Koizumi’s home.

The sign hanging outside Koizumi’s home.

“The story dates back to 1659, when the head of the Nanbu Domain, Nanbu Shigenao, invited the Kyoto-based artisan Koizumi Nizaemon to move to Nanbu in order to foster iron casting in the area. That is the starting point of nanbu-kama. The production of the cast-iron kettles, tetsubin, began around a century later, circa 1750, when the third Koizumi to take the helm invented an iron kettle with a pouring spout and handle.”

Under the patronage of the Nanbu Domain, three other family firms engaged in the production of cast-iron items—the Arisaka, Suzuki, and Fujita families—but the Koizumi family remained at the heart of the industry.

A typical work by Koizumi Nizaemon (photography courtesy of Okamaya).

A typical work by Koizumi Nizaemon (photography courtesy of Okamaya).

In the centuries that followed the reputation of nanbu cast-iron products steadily rose both in Japan and, later, in other countries, until it became the established brand that it remains today.

But there have been many ups and downs along the way. During World War II, for instance, all cast-iron production was banned with the exception of military supplies; this meant that only 16 of the 150 or so cast-iron craftsmen in the area continued to be employed in this sector. Although the production of cast-iron kettles picked up after the war, another slump came in the 1960s, when the switch to the use of propane gas and rise of aluminum products caused kettles to disappear from many homes.

Recently the tide has changed again, however, as the popularity of the cast-iron kettles has been revived. People have gained a fresh appreciation of what cast-iron products have to offer, not only in terms of the traditional tea ceremony and other such customs but also as a practical kitchen item. The aesthetic charms of the kettles have also won many admirers overseas, and some makers have capitalized on this popularity to expand their exports to Europe, the United States, and elsewhere.

Iron-clad Benefits

Koizumi Nizaemon explains more about the positive attributes of cast-iron kettles:

“First of all, there are the health benefits. About one in five Japanese today are either anemic or pre-anemic, it is said, but studies have clearly shown that drinking water that has been heated in an iron kettle can provide an iron supplement. A second point is simply that this water also tastes good; it’s great for making tea or coffee and also adds flavor when used in cooking. And then there is the aesthetic pleasure of the kettle itself. Contemplating a traditional cast-iron kettle or pot is a soothing change of pace in our modern lives.”

These days Koizumi’s firm is struggling to keep up with orders, especially with the boom in demand from China. For around half a year after the March 2011 earthquake the company received almost no orders. Subsequently, though, four or five Chinese companies placed orders through a Japanese trading company on the scale of 5 or 10 items a month. Unfortunately Koizumi had to turn down the request because it was beyond his production capacity.

This limit is clear from a visit to the workshop, where all the production is handled by Koizumi and his son. Producing a kettle is a process that involves upwards of 100 different detailed operations. Performing these various operations on a number of items in different stages of production at a given time is a daunting task.

Koizumi’s son, Takehiro, at the workshop.

Koizumi’s son, Takehiro, at the workshop.

Iwate’s Cast-iron Artisans

Koizumi along with his kettles and metal molds at the workshop.

Koizumi along with his kettles and metal molds at the workshop.

Currently in Iwate Prefecture there are 74 enterprises (including Okamaya) involved in cast-iron production under the unified Nanbu Tekki brand, according to the Tōhoku Bureau of Economy, Trade, and Industry. These firms employ an estimated total of around 730 employees and combine to produce goods valued at roughly ¥9.2 billion.

In handling orders, Okamaya usually sends a product catalog to customers upon request. If the product a customer orders from the catalog is not available, it is usually necessary to wait a month or so until the order can be filled. In some cases, it can take six months to a year for a customer to be supplied with a product. The cast-iron kettles range in price from ¥50,000 up to around ¥300,000. In addition to kettles and pots, the company produces a range of other cast-iron goods, including vases, ashtrays, and various cooking vessels.

Some of the kettles in Koizumi’s home.

Some of the kettles in Koizumi’s home.

The company is increasingly receiving orders from overseas as well, although at this point it is only able to respond to requests in English.

Even with this global interest, Okamaya remains very much rooted in the local region. In particular, Koizumi’s firm is focused on helping to foster the next generation of artisans needed to sustain the traditional craft. Koizumi notes that it takes around 10 years of experience on the job to develop into an able artisan—although he hopes that his protégés will be able to develop at an even faster pace.

Although Koizumi is capable of handling all of the work today together with his son, he is committed to spending the rest of his life on the job. Koizumi also welcomes students from the local area and elsewhere who are interested in learning about the craft, taking advantage of those opportunities to stress the importance of extending the tradition into the future.

Corporate data

Company name: Okamaya

Address: 11-18 Kiyomizu-cho, Morioka, Iwate Prefecture 020-0875

Representative: Koizumi Nizaemon

Business: Production and sale of Nanbu Tekki cast-iron products

Tel./Fax: +81-19-622-2355

Website: http://www.nanbutetsubin.com

(Photographs and original Japanese article by Harada Kazuyoshi, senior editor at the Nippon Communications Foundation.)

Iwate Prefecture Koizumi Koizumi Nizaemon tea ceremony nanbu-tetsubin cast iron kettle Okamaya