Myanmar Rail Loop Gets an Upgrade

Politics- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Chronic Traffic Congestion

Some 7.3 million people live in the metropolitan area of Yangon, Myanmar’s largest city. While the population has grown by 80% over the past three decades, the city’s creaking infrastructure is the legacy of Myanmar’s years of international isolation under military rule.

Viewed from the rooftop of a building 5 kilometers to the north, the highways of central Yangon are jam-packed with buses and taxis at half past eight on a weekday morning. A Japanese worker based locally describes the congestion as similar to Bangkok 30 years ago. The city center has only two main highways running north to south, and there are insufficient roads traveling to east and west. Local authorities have been unable to make a breakthrough to ease congestion.

Lines of vehicles progress slowly toward the city center.

Lines of vehicles progress slowly toward the city center.

There are almost no rail options; the reliance on buses is one cause of chronic traffic congestion. In January 2017, the Yangon regional government unified all private services into one network, the Yangon Bus Service. The overhaul simplified the complex web of routes, putting a limit on how many passed through the city center, but it was just a drop in the bucket.

Many businesses in the city run shuttle services for employees using minibuses or trucks with attached roofing. According to a local resident, whether an employer’s service stops near one’s residence or not is a big factor in deciding where to work. There is also a boom in imported used cars from Japan being repurposed as taxis. The regional government is considering introducing a cap on taxi numbers.

Many of Yangon’s buses are imported used from China.

Many of Yangon’s buses are imported used from China.

Workers for a small company returning home on the back of a truck with attached roofing.

Workers for a small company returning home on the back of a truck with attached roofing.

A Transport Option People Can Use

Yangon is expected to grow further, and the population is projected to hit 10 million in the 2030s. The authorities’ ace in the hole for keeping traffic moving in the face of rapid urbanization is the ongoing major upgrade to the Yangon Circular Railway operated by Myanma Railways.

At 46 kilometers, the loop is longer than Tokyo’s 34.5-kilometer Yamanote Line. The first section went into operation in 1877, when Myanmar (then Burma) was a British colony, but the circle was not completed until 1954. Due to the aging of the vehicles and tracks, the service can now only manage an average speed of 15 kilometers per hour, meaning it takes around three hours to complete a single circuit. A loan from the Japanese government of up to ¥25 billion will help fund improvements to tracks and track beds, installation of new signaling equipment and automatic level crossings, and the purchase of 66 new Japanese carriages to form six 11-carriage diesel electric trains. Construction work has already begun, and authorities have set a provisional target of 2020 for starting the upgraded service.

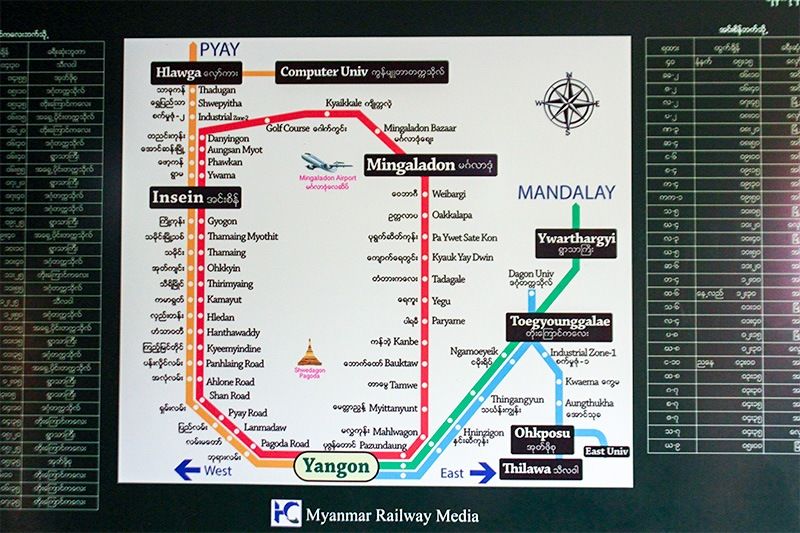

The Yangon Circular Railway is marked in red.

The Yangon Circular Railway is marked in red.

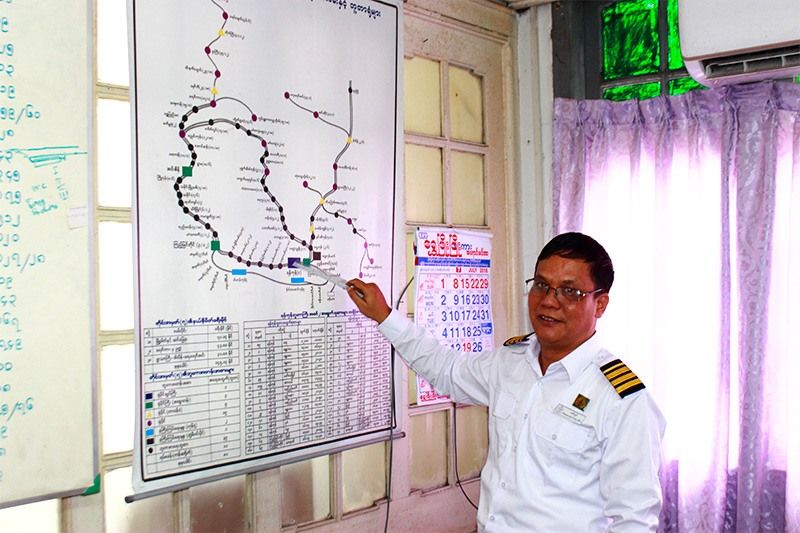

“Modernizing the YCR is the national railway’s most important project,” stresses Myanma Railways Divisional Traffic Manager U Zaw Lwin. “Once people realize that the railway is convenient and comfortable, it will ease traffic congestion to some extent.”

Myanma Railways Divisional Traffic Manager U Zaw Lwin.

Myanma Railways Divisional Traffic Manager U Zaw Lwin.

The aim is to increase the average speed of travel on the line to 26 kilometers per hour and the maximum speed to 60 kilometers per hour. This will lop 60 minutes off the time required to complete a circuit, bringing it down to around two hours. Rather than one service every 15–45 minutes during rush periods, there will be one every 10 minutes.

The area around Kyeemyindine Station, seven stops from Yangon’s main station, is undergoing development as a new urban center. U Zaw Lwin says that due to severe congestion, it currently takes 45 minutes to travel between the two areas by bus or car. “When the upgrade is complete, the train journey will take about 20 minutes. Rail travel will also be the quicker option for going between Yangon Central and the other major stations.”

In addition to large-scale redevelopment surrounding Yangon Central, Myanma Railways is inviting proposals for improvements at three other stations. Most of the city’s key government and business functions are currently concentrated to the south of Yangon Central. The reinvigorated YCR may perform the same job as Tokyo’s Yamanote Line in encouraging their dispersal and reducing congestion.

The Myanmar government is also considering building new north-south and east-west lines in Yangon to meet the needs of the swelling population. This will require a modern system, including bridges and underground sections. The Japan International Cooperation Agency has begun a feasibility study for this ambitious undertaking.

Change of Image Needed

Despite the start of work on some sections and stations, there is little awareness of the rail project among Yangon’s general public. Only around 1% of public transport users go by rail, and the YCR carries just 80,000 passengers each day.

Even when I talked to passengers at Yangon Central Station, most did not know about the ongoing upgrade work. A 66-year-old security guard returning home after work says, “The roads are packed at this time in the afternoon, so I take the train. The carriages aren’t busy, so I can sit and enjoy the ride. In the morning, I usually go by bus. When I go home, sometimes I take the train and sometimes the bus.”

There are few passengers around lunchtime at the YCR platform in Yangon Central Station.

There are few passengers around lunchtime at the YCR platform in Yangon Central Station.

At Yangon Central, the time for the next train is indicated on a handwritten sign.

At Yangon Central, the time for the next train is indicated on a handwritten sign.

The platform at this station has been raised and remodeled.

The platform at this station has been raised and remodeled.

Many of Yangon’s buses were bought used from China, and most of them were in operation at the time of the Beijing Olympics in 2008. Meanwhile, diesel trains running on the loop line have previously ended their period of usage in Japan. Some of the carriages were built more than 50 years ago.

The cheapest tickets on the YCR cost 100 kyat, or around ¥10, which is half the price of those for the bus. There is no limit to the amount of luggage, so a lot of the passengers are peddlers from the edge of the city.

Passenger carriages pulled by a battered locomotive.

Passenger carriages pulled by a battered locomotive.

Parami Station is in a residential area.

Parami Station is in a residential area.

Passengers getting on and off at Parami Station. Carriage doors are always open.

Passengers getting on and off at Parami Station. Carriage doors are always open.

Danyingon Station is located alongside a market; it can be difficult to see where the station ends and the stalls begin.

Danyingon Station is located alongside a market; it can be difficult to see where the station ends and the stalls begin.

Daw Min Min Aye, who works for a Japanese aid organization in Yangon, accompanied me around the city and interpreted for me. She says, “I took a survey of passengers on the YCR for my masters’ thesis. They tend to have comparatively low salaries. Myanmar railways today are thought of as being for people who want to travel cheaply, even if it takes a long time. This is different from Japan. I hope the new YCR is more regular and can make a contribution alongside buses and other forms of transport, so passengers feel peace of mind as they travel to and from work or school.”

(Originally published in Japanese on July 25, 2018. Reporting, text, and photography by Ishii Masato of Nippon.com. Banner photo: A diesel train arrives at Parami Station on July 11, 2018. Originally in service in Japan, it still shows its destination as Unuma in Gifu Prefecture.)