Yoshida Shōin and his Disciples

Yoshida Shōin: The Revolutionary and Teacher Who Helped Bring Down the Shogunate

History- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

In 1853 a US Navy expedition led by Commodore Matthew Perry threw Japan into turmoil with demands for it to open diplomatic relations after centuries of national seclusion. The following year, Perry returned to Japan with seven ships from the East India Squadron to press the Tokugawa shogunate for a response. By virtue of this gunboat diplomacy, he reached as far as the sea off Yokohama and on March 31, 1854, succeeded in securing the Kanagawa Treaty. This agreement opened up the ports of Shimoda and Hakodate to US vessels. While its details were being finalized, Perry’s ships remained anchored off Shimoda on the Izu Peninsula.

Before sunrise on April 25, a small boat suddenly appeared alongside the gunwale of one of these ships, the USS Mississippi, and two young samurai attempted to climb on board using the ship’s ladder. They were directed by the captain of the Mississippi to row onward to the flagship USS Powhatan, struggling through high waves before finally getting up on deck. Commodore Perry, on board the Powhatan, asked the samurai their intentions via an interpreter, and the incident was described in a report of the expedition he submitted later to the Senate.

The Commodore and the Young Samurai

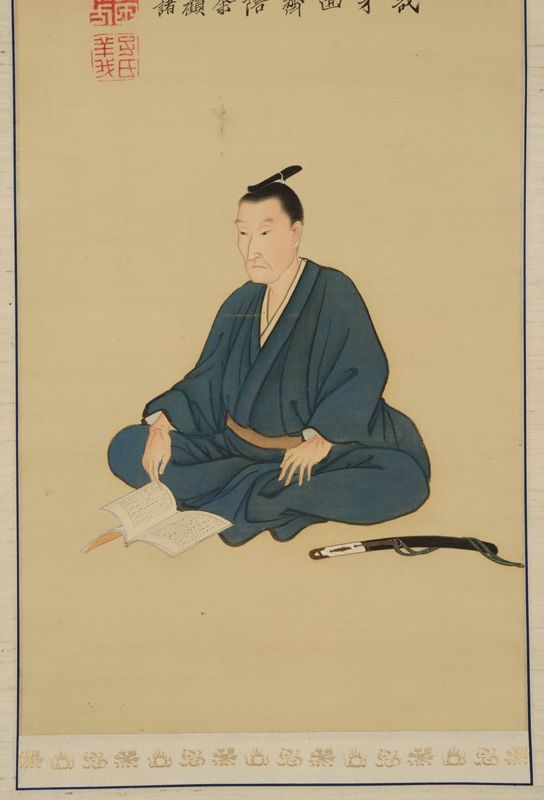

Portrait of Yoshida Shōin (courtesy of Yamaguchi Prefectural Archives).

Portrait of Yoshida Shōin (courtesy of Yamaguchi Prefectural Archives).

“They frankly confessed that their object was to be taken to the United States, where they might gratify their desire of traveling and seeing the world. . . . They were educated men and wrote the mandarin Chinese with fluency and apparent elegance, and their manners were courteous and highly refined. The Commodore, on learning the purpose of their visit, sent word that he regretted that he was unable to receive them, as he would very much like to take some Japanese to America with him. . . . They were greatly disturbed by this answer of the Commodore, and declaring that if they returned to the land they would lose their heads, earnestly implored to be allowed to remain. The prayer was firmly but kindly refused. A long discussion ensued, in the course of which they urged every possible argument in their favor, and continued to appeal to the humanity of the Americans. A boat was now lowered, and after some mild resistance on their part to being sent off, they descended the gangway piteously deploring their fate, and were landed at a spot near where it was supposed their boat might have drifted.”(*1)

Japanese people were forbidden to travel to foreign countries on pain of death at that time, and even if the Americans thought they were innocent of any wrongdoing, Perry knew that they would be considered criminals under Japanese law. But this was immediately after Japan had been forced into extraordinary compromises in the treaty that opened up the country. At this delicate stage, it was difficult to choose to break local law. The following day, Perry learned from a shogunate interpreter that the two samurai had arrived on shore, where they had been arrested by government officials. His feelings at that time appear in the report as follows:

“The event was full of interest, as indicative of the intense desire for information on the part of two educated Japanese, who were ready to brave the rigid laws of the country, and to risk even death for the sake of adding to their knowledge. The Japanese are undoubtedly an inquiring people, and would gladly welcome an opportunity for the expansion of their moral and intellectual faculties. The conduct of the unfortunate two was, it is believed, characteristic of their countrymen, and nothing can better represent the intense curiosity of the people, while its exercise is only prevented by the most rigid laws and ceaseless watchfulness lest they should be disobeyed. In this disposition of the people of Japan, what a field of speculation, and, it may be added, what a prospect full of hope opens for the future of that interesting country!”

A Martyr to the Cause

The two men were Yoshida Shōin and his disciple Kaneko Shigenosuke, samurai from the Chōshū domain (now Yamaguchi Prefecture). They were sent back to Chōshū and imprisoned in the capital of Hagi, where Shigenosuke died in 1855. However, Shōin was released under a form of house arrest. At this time, he took over his uncle’s private school, the Shōka Sonjuku, and educated young people from the area as well as writing various essays. But, infuriated by the unfair terms of the Treaty of Amity and Commerce signed between the United States and Japan in 1858, Shōin became involved in an ultimately unsuccessful plot to assassinate a senior shogunal official. Under the leadership of Ii Naosuke, the shogunate was then engaged in the Ansei Purge, a wide-ranging crackdown against antigovernment forces. Shōin was rearrested by Chōshū officials and handed over to the shogunate before being executed in 1859 at the age of 29.

Remains of the Noyama Prison in Hagi where Shōin was imprisoned.

Remains of the Noyama Prison in Hagi where Shōin was imprisoned.

In the last years of the Tokugawa shogunate, following the arrival of Perry’s ships, radical reformist activists emerged who declared loyalty to the emperor and sought to oppose pressure from foreign imperialist powers and overturn the current political system. They were called shishi or “loyalists,” and Shōin was venerated by later activists as their spiritual leader and a martyr to the cause. His boarding of the Powhatan could be seen as the first encounter between one of these shishi and the world outside Japan. Until then Perry had not been favorably impressed by the incompetence, cowardice, and irresponsibility of the shogunate leaders and bureaucrats, but the young samurai made a strong impression.

An Influential Teacher

The two-room building that housed Shōin’s private school Shōka Sonjuku is still standing in Hagi, Yamaguchi Prefecture. It is now at the center of the Shōin Shrine, established in 1907, where a museum dedicated to the samurai can also be found, and attracts numerous pilgrims as a kind of holy place for the Japanese.

Shōin came to be regarded as a spiritual leader of the Meiji Restoration, despite dying nine years before the overthrow of the shogunate and the transfer of power to imperial forces. Naturally his attempt to board the ship at Shimoda, his reputation as an early shishi, and his martyrdom in the Ansei Purge were factors in this assessment, but most important of all was the education he gave at the Shōka Sonjuku.

Shōin taught local boys at the school for just two years and several months from after his release from prison following the attempt to board the Powhatan until he was rearrested during the Ansei Purge. The students were mainly the children of low-ranking ashigaru samurai or middle-class commoners rather than those of higher-ranking samurai who could attend the prestigious domain school, the Meirinkan. Shōin himself was from a fairly low-rank samurai family and was adopted as the heir of his uncle, a military science instructor. Although he was a vassal of the Chōshū domain, he served as a teacher and researcher rather than a soldier or administrator.

As a result of Shōin’s influence, most of the more than 50 students he taught in this brief period of time later threw themselves into loyalist activities, hauling not only Chōshū but the whole of Japan toward the Meiji Restoration as the most radical of the reformists. Furthermore, several of these students became central figures in the new Meiji government that established Japan as a modern nation-state. The more successful they became, the greater they exalted their former teacher.

However, after his death and immediately after the restoration, Shōin was little known to the wider population. It was not until the 1890s that the first biography of Shōin was published in Japan. As times changed politically, assessments of his life went through various shades of praise and censure. This has meant that although a great deal has been written about Shōin, it has become very difficult to get an image of the man.

Stevenson’s Tale of “Yoshida Torajiro”

Although the first Japanese biography was not published until the 1890s, a biographical sketch appeared in English as early as 1880, written by none other than Robert Louis Stevenson, the author of Treasure Island and The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Stevenson met Masaki Taizō, a former student of Shōin, in Edinburgh and was deeply moved by his stories of Shōin’s achievements, writing a piece that would be published as “Yoshida Torajiro.” Despite the renaming of the title, the sketch gave a more vivid picture of Shōin’s appeal than any later Japanese biography.

Robert Louis Stevenson (courtesy of National Galleries of Scotland).

Robert Louis Stevenson (courtesy of National Galleries of Scotland).

Stevenson depicts Shōin, as seen by Taizō, as follows: “He was ugly and laughably disfigured with the smallpox; and while nature had been so niggardly with him from the first, his personal habits were even sluttish. His clothes were wretched; when he ate or washed he wiped his hands upon his sleeves; and as his hair was not tied more than once in the two months, it was often disgusting to behold. With such a picture, it is easy to believe that he never married. A good teacher, gentle in act, although violent and abusive in speech, his lessons were apt to go over the heads of his scholars and to leave them gaping, or more often laughing.”

He also writes in detail of the failed attempt to board the Powhatan and Shōin’s patriotism and immense energy in the crisis that Japan faced. And Stevenson extols Shōin’s strong sense of judgment in seeking to gain Western knowledge rather than emotionally striking out against the foreign threat to the nation, as well as his indomitable perseverance in refusing to give up despite repeated failure: “But he was of Thoreau’s mind, that if you can ‘make your failure tragical by courage, it will not differ from success.’ He could look back without confusion to his enthusiastic promise. If events had been contrary, and he found himself unable to carry out that purpose — well, there was but the more reason to be brave and constant in another.”

Despite the unflattering description of Shōin’s appearance given above, his charisma and influence were felt by both Perry and Stevenson and are also clear from the number of activists he molded in his own image from among the boys he taught. After completing “Yoshida Torajiro,” Stevenson described the man in a letter to a friend as “a Japanese hero who will warm your blood.”

(Originally written in Japanese by Mamiya Jun of the Nippon.com editorial department and published on January 9, 2015. Banner photo: The Shōka Sonjuku school in Hagi, Yamaguchi Prefecture.)

(*1) ^ Francis L. Hawks, Narrative of the Expedition of an American Squadron to the China Seas and Japan (Washington: Beverley Tucker, 1856).

history Meiji Restoration Matthew Perry Yoshida Shoin Choshu Ansei Purge bakumatsu