Remarkable Recovery: The Modern History of Japan’s Environment

Japanese Perceptions of Life

Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

The Japanese and Meat

Rates of meat consumption appear to have a direct correlation to income levels, trending high in high-income countries and low in low-income countries. Japan is an exception, ranking twelfth among the world’s major countries for per capita meat consumption. Japanese people only eat one-fourth the amount of meat consumed by people in the United States and less than the people of South Korea, China, and Malaysia. And despite popular conceptions about the Japanese diet, this doesn’t mean that the country’s consumption of seafood is comparatively high.

The Catholic priest Francis Xavier (1506–52), who introduced Christianity to Japan in the mid-sixteenth century, reported to the Jesuit headquarters that the Japanese were remarkably robust even though they lived on a diet of only vegetables and rice cooked with barley, occasionally supplemented with fish and fruit. Miyazawa Kenji (1896–1933), a beloved poet and a vegetarian, wrote in his famous poem, “Ame ni mo makezu” (trans. “Strong in the Rain”): “He eats four gō of unpolished rice / Miso and a few vegetables a day.”

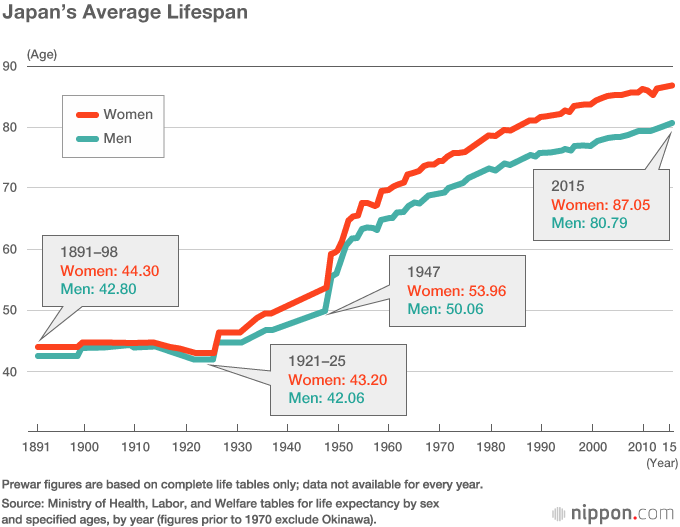

The Japanese, both men and women, had the longest average healthy lifespan of anyone in the world in 2015. Yet, back in the Edo period (1603–1868), the average lifespan was only around 45 years. The average did not exceed 50 years until 1947, after World War II, suggesting that the Japanese were not always a long-lived people.

The whole world is keen to know the secret of Japanese longevity. The prevailing opinion is that the Japanese diet—with its delicate balance of traditional rice, vegetables, and seafood combined with Western bread, meat, and dairy products—has much to do with it. Traditional Japanese cuisine, known as washoku, is popular for its healthful properties and has even been designated an intangible cultural heritage by UNESCO. There are believed to be as many as 89,000 Japanese restaurants around the world today.

The increase in meat consumption has significantly extended not only Japanese life expectancy but also the average height of the Japanese people. The average 20-year old male has become nearly 12 centimeters taller since 1950, a rise attributed to an increase in meat consumption and Western lifestyles. And yet meat consumption has remained stable over the past two decades, while seafood consumption has reverted to levels seen in the 1950s. This may in part be due to a deeply rooted traditional aversion to killing animals and eating their meat and to a health-conscious tendency that keeps meat consumption at moderate levels.

Arrival of the Whaling Ships

The 1830s to 1850s marked the golden age of American whaling. As the US economy expanded, there was growing demand for lamp oil, candles, lubricants, and other products made from whale oil, and whaling became a major industry. When the whale population in the Atlantic was depleted, the American whaling ships made their way to the Pacific, where the creatures were still to be found in abundance.

In 1846, there were 292 American whaling ships roaming the Pacific Ocean. Calculating from the whale oil production of 1853, it is estimated that more than 3,000 whales were killed in one year. The American whaling ships ranged far and wide, from the seas near Japan to the North Pacific.

Tales about the whaling ships abound. Moby-Dick, published by the American author Herman Melville in 1851, tells the fictional story of Captain Ahab, who lost a leg to a great white whale in the coastal waters off of Japan. There are as well numerous stories of American whaling ships rescuing shipwrecked sailors, among the most famous being John Manjirō (Nakahama Manjirō).

The advent of the whaling ships also meant more shipwrecks and trouble with local residents along Japan’s Pacific coast. In the 1840s and 1850s, American whaling ships stopped at Japanese ports to replenish their supplies of food and water, as well as the firewood they needed in quantity to boil whale blubber and extract the oil. There were frequently violent incidents caused by sailors who disembarked from the vessels in port.

Capturing a Sperm Whale, an 1835 painting by John William Hill. (© Yale University Art Gallery)

Capturing a Sperm Whale, an 1835 painting by John William Hill. (© Yale University Art Gallery)

Eventually, the bakufu government issued the Edict to Repel Foreign Vessels to reinforce its isolationist policy and captured sailors from whaling ships that had run aground. This led to rumors that the Japanese were torturing the shipwrecked sailors, fueling anti-Japanese sentiment in the United States.

The World’s First Wildlife Conservation Agreement

In the midst of the growing demand among American whalers and the general American population for better treatment of their shipwrecked sailors, Commodore Matthew C. Perry of the US Navy was dispatched to Japan to demand the opening of the isolated country. He arrived at Uraga in Kanagawa Prefecture in July 1853 with four black ships and stayed until he was able to present a letter to the Tokugawa government from the US president demanding that Japan open its shores.

Perry returned the following year to negotiate the Japan-US Treaty of Peace and Amity (the Convention of Kanagawa), which was signed on March 31, 1854. Two months later the treaty was modified to set forth the terms of agreement in greater detail.

The treaty allowed American ships to purchase supplies, such as firewood, food, and water, and opened the ports of Shimoda and Hakodate to American vessels, thereby effectively bringing the years of Japan’s isolation to an end. The 13 articles that were later added to the treaty specified the extent to which Americans could move on Japanese soil, where they could find lodgings while in the country, and even where their graves were to be located if they died while in Japan.

Of particular note is Article 10 of the modified treaty, which was included at Japan’s request and which states that Americans will respect the prohibition in Japan of all hunting of wild birds and animals.

The first international discussion on protecting wild birds, and the origin of numerous agreements and organizations for the protection of birds, is said to have taken place in Paris in 1895, but the provision in the modified Japan-US Treaty of Peace and Amity is probably the oldest formal wildlife conservation agreement in the world.

American “Barbarians”

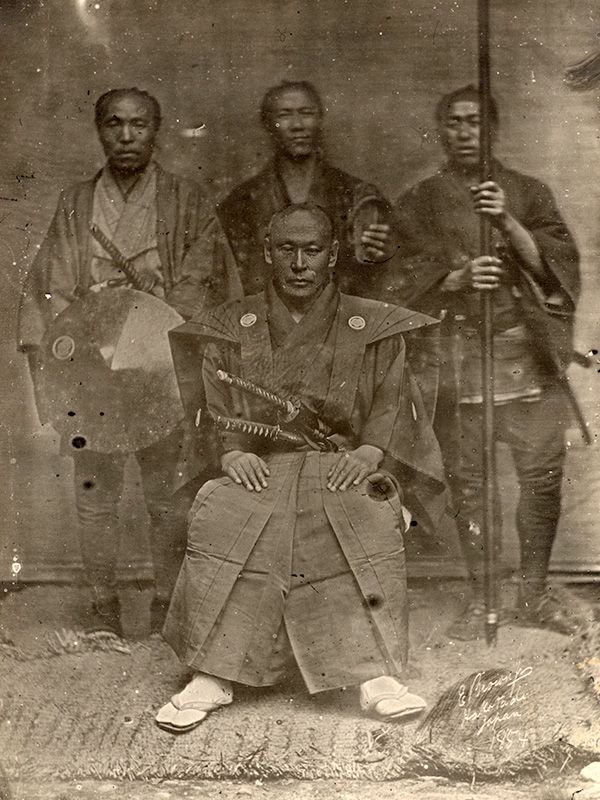

An 1854 daguerreotype of Ishizuka Kanzō and his attendants made by Eliphalet Brown, Jr. (Courtesy Hakodate City Central Library)

An 1854 daguerreotype of Ishizuka Kanzō and his attendants made by Eliphalet Brown, Jr. (Courtesy Hakodate City Central Library)

The article prohibiting hunting came out of the following background. About a month before the signing of the treaty, Perry sailed with his black ships to Hakodate, one of the ports being considered for opening to American ships. This visit is recorded in detail in the Akokuraishiki (Arrival of the Americans), a document preserved in the Hakodate City Central Library. The record was written by Ishizuka Kanzō, a samurai of the Matsumae domain. The daguerreotype of Ishizuka taken by a photographer accompanying the Perry mission is the oldest known photograph in Japan and has been designated an important cultural property.

In the Japan of the Edo period, senseless killing was considered unethical, and because hunting was relatively rare, wild birds and animals showed little fear of humans. The Americans, however, found it entertaining to shoot at the birds that landed on their ships’ masts and decks. Ishizuka reports with disgust in the Akokuraishiki that “the foreigners disembarking at the beaches of Kameda, Nanane, and Arikawa kill birds with tow ropes and pistols and then return to their ships at 4 pm.” The local people observing this behavior were dismayed by the barbarity of the Americans.

In The Japan Expedition, however, Perry claims that while they observed numerous wildfowl such as geese and wild ducks, his men were only able to kill a few.

The Americans who visited Japan from the end of the Edo period to the beginning of the Meiji era were impressed by the abundance of wildlife in Japan and the affinity of the Japanese people for animals. One of these Americans was the veterinary scholar Edwin Dun, who had been hired in 1873 to provide advice on developing Hokkaidō. He reports on his first walk through the city of Tokyo that he observed pheasants in the grass, and that the moat around the imperial palace in front of the British embassy was black with wild geese, ducks, and other water birds. Furthermore, he claims to have come home to find a fox eating off of his dining room table.

Tokyo was one of the largest cities in the world at the time; Dun was amazed at how people and wild animals seemed to be able to coexist in such an environment. He did much to help modernize the livestock industry in Japan, ending his stay as the American envoy to the country. The common dandelion that now flourishes in Japan is believed to have been inadvertently introduced by Dun when he brought in seeds for pasture grass.

Making Compassion for Living Things the Law

The fifth shōgun, Tokugawa Tsunayoshi (1646–1709), issued in 1687 a series of Edicts on Compassion for Living Things (Shōrui awaremi no rei). There were a total of 135 edicts. It is said there were so many because people did not abide by them. “Living Things” referred to a wide range of creatures including dogs, cats, birds, fish, shellfish, and even insects. Forty of these edicts, the highest number, were issued for birds alone, followed by 33 for dogs and cats and 17 for horses.

In historical dramas, the edicts are portrayed as cruel laws leading to the arrests of hundreds of thousands of people, but in his work Edo no idenshi (trans. The Edo Inheritance), Tokugawa Tsunenari, the eighteenth head of the Tokugawa house, asserts that in the 24 years in which the edicts were in effect, only 69 people were arrested and punished, 13 of whom were executed.

The edicts were actually primarily intended as moral injunctions for the protection of the weak and helpless, such as orphans, old people, the sick, and the abandoned. There were provisions, for example, that called for the execution of anyone who would steal the clothing of a traveler fallen by the wayside or who would throw a child into a river.

Regarding abandoned children, the edicts urge people to take a child in as their own or give the child to someone who will care for it instead of going to the authorities. Towns were instructed to register abandoned children, and facilities were built to take in the poor and destitute travelers.

The reason so many of the edicts concerned dogs—particularly prohibitions against abandoning dogs and requirements for registering dogs—was probably because wild dogs were proliferating in the streets of Edo and dog attacks were occurring with increasing frequency. Tsunayoshi came to be known as the Dog Shōgun because of these edicts which were probably the first legal measures for the protection of animals anywhere in the world—it is difficult to find an equivalent until the laws protecting animal rights in Britain that were enacted in 1911.

Holding facilities for dogs were built in the Ōkubo, Yotsuya, and Nakano districts of Tokyo. The facility in Nakano is said to have been especially large, covering 100 hectares of land, and at its peak housed more than 80,000 dogs. Today there are five dog statues next to the Nakano municipal office commemorating the spot where the facility is believed to have been located.

The five dogs commemorating the holding facility ordered by Tokugawa Tsunayoshi, the Dog Shōgun, in front of the Nakano municipal office. (© PIXTA)

The five dogs commemorating the holding facility ordered by Tokugawa Tsunayoshi, the Dog Shōgun, in front of the Nakano municipal office. (© PIXTA)

Tokugawa Tsunayoshi’s reputation has been recovering in recent years, and some Japanese history schoolbooks even laud the Dog Shōgun for his “compassionate politics.” The German physician Engelbert Kaempfer (1651–1716), who twice met with Tsunayoshi, recalls him as a truly wise and great leader in his journal of his visits to Edo.

Defying Taboos

An excavation of the ni-no-maru section of the original Okayama Castle carried out by the board of education of Okayama, Okayama Prefecture, found numerous animal bones dating to the Edo period. Professor Tomioka Naoto of the Okayama University of Science has identified the bones as belonging to wild boar, pigs, cows, wild rabbits, tanuki, dogs, wolves, and badgers. The bones bear cut marks, making it certain that the animals were butchered and eaten by humans. The ni-no-maru section of the castle was reserved for the living quarters of the chief retainers, suggesting that upper class samurai had no compunctions about eating meat. There have been similar findings at the Akashi Castle in Hyōgo Prefecture. It would seem that the old prohibition against eating meat was rather superficial.

(Originally published in Japanese on June 19, 2017. Banner photo: Lithograph by Wilhelm Heine of the Perry Expedition’s arrival at Yokohama on March 8, 1854. Perry wrote in his journal of seeing numerous birds while he was in Japan. © Aflo.)