“Asahi Shimbun” Coverage of the Comfort Women Issue Through the Years

Politics Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Facts Unchanged by Asahi’s Assessment

One thing needs to be made clear at the outset: wartime “comfort women” did in fact exist across Asia during World War II, with the involvement of Japan and the Japanese military. It is also undeniably true that there were numerous instances of local women in war zones being forced into sexual service under threat of military violence. In this respect, their plight is no different from the violence perpetrated by occupation forces in other wars.

The emphasis here, though, is on “war zones.” The comfort women system itself was simply an incarnation of Japan’s officially approved system of managed prostitution taken to areas occupied by the Japanese military. (Japan abolished its managed prostitution system in 1958.) The majority of comfort women consisted of Japanese women in mainland Japan, as well as women in Korea and Taiwan, which were annexed to Japan at the time. Managed prostitution was no less than officially sanctioned human trafficking, and there is no question that it grossly violated the human rights of those subject to it. But this human rights violation was altogether different from coercion in war zones, which is a war crime.

South Korea has been highly vocal against Japan on the issue of comfort women in recent years, the gist of the criticism being that it was a war crime. But Japan has not waged war on the Korean Peninsula since its 1894–95 war with Qing-dynasty China. It has not, moreover, fought a single modern war with countries of the Korea Peninsula.

A Hoax Created by Yoshida Seiji

Yoshida Seiji. (© Yomiuri Shimbun/Aflo)

Yoshida Seiji. (© Yomiuri Shimbun/Aflo)

Be that as it may, the comfort women issue is still treated as a war crime in South Korea, as it also was in Japan up until a certain point. One factor underpinning this is a lie: the testimony of a man by the name of Yoshida Seiji (1913–2000). Yoshida claimed to have worked during World War II as a labor mobilization manager at the Shimonoseki branch of the Yamaguchi Prefecture Rōmu Hōkokukai, an organization that oversaw day laborers. He published two books in the 1980s, in which he wrote that he had “hunted out” roughly 200 young women on Jeju Island during wartime. Years later, when the issue blew up, reporters, historians, and even Korean researchers conducted surveys on the island to confirm the facts, but none of them was able to find evidence or testimony supporting his account.

If this were the whole story, Yoshida’s tale would have faded into oblivion without gaining much public attention. But as fate would have it, the Asahi Shimbun—Japan’s most influential newspaper since before the war—wrote up the testimony in an article in 1982. “Comfort women hunting” in the Korean Peninsula thus made Korean headlines and became a central issue in the country’s criticism of Japan.

Things were further complicated by the way that the Asahi mixed up joshi teishintai (women’s volunteer corps), in which Japanese citizens were gathered to volunteer their labor during the war, with comfort women. Women’s volunteer corps existed throughout Japan and its territories, primarily in schools. This led to widespread discourse based on the assumption that “comfort stations” were highly common.

Summary of the Asahi Assessment of Its Comfort Women Coverage

1. Existence of coercive recruitment

Regarding the September 2, 1982, article in the Osaka morning edition about “comfort women hunting” on Jeju Island, which was based on the testimony of Yoshida Seiji, and the description in an editorial on January 12, 1992, that women were “solicited or forcibly taken away as volunteer corps”:

In Korea and Taiwan, which were under Japanese colonial rule, prostitution rings were able to deceptively recruit large numbers of women with promises of good work, and no records have been found of the Japanese military systematically abducting women for sexual purposes. In regions occupied by the Japanese army, including Indonesia, records indicating that the military carted off local women have been confirmed. In both cases, the women were forced into service against their will.

2. Yoshida Seiji’s testimony about “comfort women hunting” on Jeju Island

Regarding having run 16 articles based on Yoshida’s testimony since becoming the first major media outlet to take up the testimony:

Asahi conducted additional research on Jeju Island but was unable to obtain information corroborating Yoshida’s testimony. Judging the testimony to have been false, it retracted the articles.

3. 1992 article and political intent

Regarding the criticism that the January 11, 1992, story on a document indicating military involvement in comfort stations was timed to coincide with Prime Minister Miyazawa’s visit to Korea:

There was no such intention, and Asahi ran the article five days after learning the details. Meanwhile, the government had been notified of the document’s existence prior to the article being printed.

4. Confusion of volunteer corps with comfort women

Regarding the 1991–92 articles stating that comfort women from the Korean Peninsula were forcibly recruited under the pretext of joining the joshi teishintai (women’s volunteer corps):

Joshi teishintai refers to the joshi kinrō teishintai (women’s volunteer labor corps), which mobilized women to work in munitions factories and other locations during the war, and is completely distinct from comfort women. Some of the reference materials used by the reporters also confused the two, resulting in misuse of the term.

5. Background of the August 11, 1991, article on the first testimony by a former comfort woman

Regarding allegations that the article, which preceded Korean media coverage, was somehow biased, because its writer was related to a senior member of a Korean organization supporting lawsuits by former comfort women:

What prompted the story was information provided by the chief of the Seoul bureau of the time, and there was no intentional distortion of facts.

The Tide-Turning Coverage of January 1992

Coverage along these lines reached a climax around the time of Prime Minister Miyazawa Kiichi’s visit to South Korea in January 1992. The previous year, a former comfort woman had come forward for the first time and sued the Japanese government. As with the Yoshida testimony, Asahi wrote up the story ahead of Korean media. In the midst of the commotion, just days before Miyazawa left for Korea, Asahi reported on a document suggesting that the Japanese military and public agencies had facilitated the transportation of comfort women to “comfort stations.” The prime minister was obliged to repeatedly apologize during his visit, and the next year Chief Cabinet Secretary Kōno Yōhei released a statement regarding the comfort women issue. (Although the statement acknowledged the existence of comfort women, public-sector involvement in operating comfort facilities, and coercion in war zones, it made no mention of coercion in Korea.) Other media organs began following in Asahi’s footsteps.

With the government being forced into action, the articles to date quickly came under scrutiny, the outcome being that Yoshida’s testimony had no basis in fact and that the volunteer corps and comfort women had been mixed up. From August 1992 onward, Japanese media refrained from coverage based on the testimony. But they neither retracted nor corrected past articles.

Japan and Korea in Deadlock

The situation further escalated, even as the media fell silent on the subject. In 1996 Radhika Coomaraswamy submitted an addendum to her report to the United Nations Commission on Human Rights, taking up Yoshida’s testimony as evidence. Seven Korean former comfort women came under domestic attack for accepting reparations from the Asian Women’s Fund, an organization set up by Japanese government initiative to compensate former comfort women across Asia, and were later cut off from government support. Even today, the overwhelming attitude in South Korea is that they cannot accept reparations or apologies unless Korean comfort women are treated as victims of coercion in war zones and not along the lines of the Kōno Statement.

The Korean stance was publicized in the United States in a campaign led by Korean Americans, culminating in a 2007 resolution by the House of Representatives condemning Japan. In March 2007 Prime Minister Abe Shinzō, then in his first term, had remarked that “there was coercion of these women in the broad sense, but not in the narrow sense”—in other words, that comfort women existed in Korea as a product of human trafficking, but that there had been no coercion on the direct part of the Japanese military. This only earned him the reputation of a historical revisionist from both the government and people of the United States.

The Japanese government, for its part, could not possibly provide a response above and beyond that of the Kōno Statement, which would entail acknowledging Yoshida’s “lie” as fact. And so Japanese-Korean relations fell into an impasse with no foreseeable way out.

Syngman Rhee’s Myth of Wartime Victory over Japan

Koreans did not actually start out with a sense of victimhood regarding the issue of wartime comfort women. If highly criminal acts had in fact been committed, Korea would have raised the issue immediately after the war, as the Netherlands did in the postwar trials of Class B and C war criminals. In reality, it was not until the 1980s that “coerced comfort women” came to be talked about, and only after testimony and media reports came out in Japan.

Once the image of wartime women forced into sexual slavery was set forth, however, it spread immediately. South Korea had good reason to embrace the image.

The state of South Korea was born as a consequence of the former Japanese territory of Korea being divided at the end of World War II. Both North and South Korea came into being because the Empire of Japan fell, not because they won independence with their own hands. But with both countries being exclusivist in nature, the Korean War broke out, and a long and fierce clash of national identities has continued since then.

Early on, the North had the upper hand in this conflict. North Korea has its origins in a resistance movement based in the Yanbian district of Jilin, Manchuria, after Japan’s annexation of Korea. Led by anti-Japanese partisan groups with the backing of the Communist Party of China, this movement claimed to be the true leaders of independence. The predecessor of South Korea, meanwhile, was the provisional Korean government, which aligned itself with the Kuomintang government of China. Syngman Rhee, South Korea’s first president, was also president of the provisional government. This government in exile formed an armed force known as the Korean Liberation Army during the Sino-Japanese War of 1937–45, but this force never fully functioned and did not actually engage in battle against Japan. Nor did the government ever win the formal recognition of the international community. Moreover, the Kuomintang government, its sponsor, lost the civil war with the Communists, which supported North Korea, and retreated from the mainland to Taiwan in 1949.

Nonetheless, in the Korean War over unification of the peninsula, the South Korean administration of Syngman Rhee held firmly to the line of its “history of resistance against Japan.” Accordingly, it asked to be invited to the San Francisco Peace Conference of September 1951 between Japan and the Allied powers and other members of the international community, as well as to be included as a signatory of the treaty. In short, it demanded that the international community acknowledge South Korea as a victor over Japan in World War II. The Allies refused, but South Korea continued to conduct itself as a victor, both at home and abroad.

Unreasonable Comparisons with Germany

The echoes of Rhee’s myth live on to this day. South Korean critics of Japan, whether politicians, organizations, or the media, almost invariably compare Japan with Germany. Regarding the territorial dispute over Takeshima, in particular, they have repeatedly brought up the German-Polish Border Treaty, suggesting that Japan follow Germany’s example. In the treaty, signed at the time of its reunification in 1990, Germany settled its border dispute with Poland and relinquished the rights of German refugees to make territorial claims.

In truth, drawing a parallel between South Korea and Poland is a stretch. Poland had undisputedly been at war with Germany and was, moreover, a direct victim of Nazi war crimes. But South Korea, as noted above, was never at war with Japan during World War II. Whether residents liked it or not, the Korean Peninsula was part of Japan at the time. South Korea thus had a good motive or psychological basis for wanting to present itself as a country that had warred with Japan, and the issue of “coerced comfort women” gave it a way to be seen in the same light as wartime Poland or the territories later occupied by the Soviet Union.

The Japanese Media’s War Involvement

The psychological inclination to portray South Korea as World War II victims was also seen among certain elements in Japan, specifically among the media. Here again, a comparison with Germany is a good illustration.

In both Japan and Germany, according to the terms of surrender to the Allied powers, those held responsible for the war were prosecuted in military trials, and the wartime regimes dismantled. The Nazis and Nazism were done away with in Germany as the culprits of war, while the military and militarism were eliminated in Japan. The disbanding of the military and the purging of those involved was more thorough in Japan than in Germany. But this was true only with regard to the military. While a discussion of the circumstances surrounding the process is beyond the scope of this article, the bottom line was that, aside from the zaibatsu (financial and industrial conglomerates) being taken apart, virtually all of Japan’s nonmilitary leadership was left intact, including politicians, the bureaucracy, and universities.

The most prominent of these examples were media organizations. In Germany, war collaborators were systematically dissolved or expelled in the postwar process of negating Nazi propaganda, and newspapers were not exempted from this fate. Japan and Germany greatly differ in that respect.

From the 1931 Manchurian Incident onward, the Asahi Shimbun, Mainichi Shimbun, and Yomiuri Shimbun, Japan’s three major newspapers since the prewar era, fed the enthusiasm for the invasion of mainland China as virtual mouthpieces of the military. Circulation of the three dailies skyrocketed, and as of 1945 Asahi and Mainichi were each selling 3.5 million copies daily, while the newer Yomiuri had a circulation of 1.5 million. All three had established their status as national newspapers by this time. Although the US Occupation banned Ogata Taketora, chief editor of Asahi, and Shōriki Matsutarō, president of Yomiuri, from public office under suspicion of war crimes, the purge did not extend far beyond them, and was lifted before long. Aside from the breakup of the Dōmei News Agency into Jiji Press, Kyodo News, and Dentsu, Japan’s media organizations were unaffected, even down to their nameplate designs.

Shift of Authority from Politics to the Media

The sway of Japanese media organs over public opinion, which they built up during the war as instruments of propaganda under the National Mobilization Law, only grew stronger in the postwar decades. This stems in part from the government and public agencies preferentially passing on information to the media under the press club system. In effect, the wartime system of general mobilization has continued.

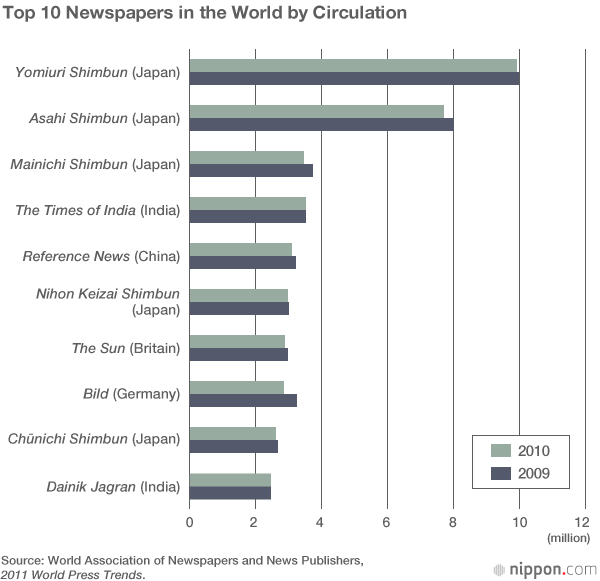

With no more military control, topped with greater influence, Japan’s national newspapers and other media giants have come to hold enormous clout. The figure below gives a good picture of just how much of a presence they have in Japan. Yomiuri and Asahi are the top two newspapers by circulation anywhere in the world. Considering that China and India have populations 10 times larger than Japan and that Japanese is used almost exclusively within the country, Japan’s share of the global market is remarkable. The Soviet Pravda and Chinese People’s Daily were said to have had circulations of 15 million and 10 million, respectively, in the final days of the Cold War. Compared with these numbers, the domestic presence of Japan’s mammoth newspapers is extraordinary.

When Japan lost the war, the government also lost its authority regarding historical issues and other matters of values, and journalism and academia took over the leadership in forming public opinion. Issues involving history and war responsibility became topics in which the media held the overwhelming advantage over the government and political authority. The media needed to be champions of justice, all the more because of their own part in the war. Thus, historical issues with Japan’s nearest neighbor became a favorite topic for Japanese newspapers.

Asahi’s Far-Overdue Retraction

Asahi did the right thing in reviewing its past coverage of the comfort women issue and admitting its errors. But the gesture came much too late. Fully 32 years had passed since the first article on Yoshida’s testimony came out and 22 years since the government was obliged to act and the testimony lost its credibility. In the interim, the image of “comfort women forced into service” became ingrained in Korean public opinion, and the global community came to perceive it as a centerpiece in the question of Japan’s wartime responsibility.

To international eyes, the points of contention between Japan and South Korea are trivial details in the overall issue of Japan’s comfort women. What matters is Japan’s attitude toward the wartime comfort women issue as a whole, as well as toward the even larger issue of its responsibility for the war. But the moment Japan tries to correct its own error, however “trivial” the error may be, the outside world interprets this as an attempt to revise history. That South Korea has the intention of taking political advantage of the issue is beside the point. In this respect, Japan is still the defendant.

Within Japan, moreover, there exists pressure to deny not only the country’s responsibility regarding comfort women but all of its other wartime responsibilities on the ex post facto grounds of small inaccuracies. This pressure has further constrained Japan’s actions.

Meanwhile, South Korea has continued to promote the fiction created by Syngman Rhee in its recent course of cozying up to China. China, too, is beginning to answer to this call. Although Japan has yet to truly realize the severity of the situation, China’s commendation of the Korean Liberation Army and remarks about Chinese-Korean cooperation in the struggle against Japan have important foreign policy implications for South Korea. China had long regarded North Korea as the legitimate government of the Korean Peninsula. As the prospect of North Korea’s collapse and North-South unification becomes more real, it is likely that South Korea will step up its campaign for both domestic and international recognition of Rhee’s version of history as the basis for unification.

Retracting past coverage will not wipe the slate clean. The fictitious accounts of history perpetuated by both Japan and South Korea have had consequences far more grave and sinful than the “lie” told by Yoshida that started it all.

(Originally written in Japanese by Mamiya Jun, Editorial Department.)

Timeline of “Comfort Women” Coverage and Historical Issues

| 1977 | Comfort women issue | Yoshida Seiji publishes Chosenjin ianfu to Nihonjin: Moto Shimonoseki rōhō dōin buchō no shuki (Korean Comfort Women and the Japanese: A Former Shimonoseki Labor Mobilization Manager’s Memoir). |

|---|---|---|

| 1982 | Media | September 2: In the Osaka morning edition, the Asahi Shimbun prints an article on Yoshida’s testimony about hunting for comfort women on Jeju Island. Asahi would go on to publish 16 articles regarding Yoshida’s testimony. |

| Historical issues | June 26: Major newspapers and television networks report that a reference in a high school history textbook to Japan’s “aggression” into northern China had been rephrased as an “advancement” during the Ministry of Education’s authorization process. July–August: The textbook problem becomes a diplomatic issue. The Education Ministry announces that no such change had been made, and media outlets admit after further review that the report had been false (caused by an error by a Nippon Television reporter). An “Asian neighbors clause” is added to the textbook authorization standards. | |

| 1983 | Comfort women issue | Yoshida publishes Watashi no sensō sekinin (My Wartime Responsibilities). |

| 1989 | Comfort women issue | A Korean translation of Watashi no sensō sekinin is published. |

| 1990 | Comfort women issue | October: 37 women’s organizations in South Korea issue a statement making six demands to the Japanese government, including an acknowledgment that comfort women were recruited coercively, a formal apology, and compensation. November: The Korean Council for the Women Drafted for Military Sexual Slavery by Japan (Chongdaehyop) is established. |

| Historical issues | October: Germany is reunified. November: The German-Polish Border Treaty is signed. Until this time, East Germany had neither formally recognized the eastern border with Poland defined in the Yalta Agreement (Oder-Neisse line) nor relinquished the rights of German refugees from the former eastern territories to make territorial claims, but the treaty resolves both issues. | |

| 1991 | Media | August 11: Asahi, ahead of Korean media, runs an article based on a taped testimony by the first former comfort woman to go public on an anonymous basis. August 14: The Hokkaidō Shimbun prints an exclusive interview of the woman with her real name included. August 15: Major Korean newspapers report on the story. |

| Comfort women issue | August: A former comfort woman comes forward for the first time in South Korea. Japanese and Korean media cover the story, both of which confuse the volunteer corps with comfort women. The Japanese government begins investigations. October 1991–February 1992: The Korean network MBC airs a television series in which a comfort woman is the protagonist. December: Former comfort women who went public file a lawsuit against the Japanese government, led by Japanese human rights lawyers; the Japanese Supreme Court rejects the claim in 2004. | |

| 1992 | Media | January 11: Asahi carries an article titled “Ianjo: Gun kan’yo shimesu shiryō” (Document Indicating Military Involvement in Comfort Stations) in its morning edition. January 12: Asahi’s editorial, “Rekishi kara me o somukemai” (We Will Not Look Away from History), again confuses the volunteer corps with comfort women. Following these articles, domestic and foreign media report on Yoshida’s testimony, specifying the numbers of individuals who were coercively recruited. But after scholars identify the testimony as being fictitious, domestic media refrain from coverage premised on the testimony from August onward. July–August: Based on records of the postwar trials of Class B and C war criminals, Asahi reports on the forced recruitment of numerous Dutch women as comfort women in the former Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia) during the war. |

| Comfort women issue | January: Following the articles by Asahi, Korean media report on the issue in unison, confusing the volunteer corps with comfort women. January 16: Prime Minister Miyazawa Kiichi visits South Korea and apologizes at the bilateral summit. March–April: Historian Hata Ikuhiko conducts research on Jeju Island and discloses his conclusion that Yoshida’s testimony had been fabricated. April: The government releases its findings, acknowledging cases of public-sector involvement at comfort facilities across Asia. | |

| Historical issues | August: China and South Korea formally establish diplomatic relations. | |

| 1993 | Comfort women issue | August: The “Statement by the Chief Cabinet Secretary Yōhei Kōno” is issued. |

| 1994 | Comfort women issue | August: Prime Minister Murayama Tomiichi makes a statement toward resolution of the issue. |

| Historical issues | January: The government of the Netherlands releases documents regarding Dutch comfort women in the former Dutch East Indies. China begins patriotic education. | |

| 1995 | Comfort women issue | January: Yoshida Seiji admits in the Shūkan Shinchō magazine that his books are fictional. July: The Asian Women’s Fund, a private entity, is set up by government initiative. August: The Murayama Statement is issued on the fiftieth anniversary of the end of World War II. |

| 1996 | Comfort women issue | January: The UN “Coomaraswamy Report” addendum citing Yoshida’s testimony is submitted. |

| 1997 | Comfort women issue | January: The Asian Women’s Fund makes compensation to seven Korean women. The individuals are denounced as traitors in South Korea. |

| 1998 | Media | March: Yoshida Seiji refuses to be interviewed by Asahi. Asahi writes that it “could not verify the authenticity” of his testimony. |

| Comfort women issue | March: In response to a request from Chongdaehyop, South Korea’s Kim Dae-jung administration withdraws support for the seven women who accepted compensation from the Asian Women’s Fund. | |

| 2000 | Historical issues | July: The United States and Germany agree on the establishment of “Remembrance, Responsibility, and the Future,” a foundation for handling lawsuits against German companies. |

| 2001 | Comfort women issue | January: NHK airs “Towareru senji sei-bōryoku” (Questioning Wartime Sexual Violence,” the second episode of the series Sensō o dō sabaku ka (How to Judge the War). The program becomes controversial in 2005. |

| Historical issues | A junior high school history textbook by the Japan Society for History Textbook Reform passes government screening. August: Prime Minister Koizumi Jun’ichirō makes his first visit to Yasukuni Shrine. | |

| 2004 | Historical issues | June: In South Korea, the Roh Moo-hyun administration enacts the Special Law on Sex Trade. (Japan’s Anti-Prostitution Act went into force in 1957.) |

| 2005 | Media | January: Asahi takes up the NHK TV program aired in January 2001 under the headline, “NHK ‘ianfu’ bangumi kaihen: Nakagawa Shō, Abe shi ‘naiyō katayori’ zenjitsu, kanbu yobi shiteki” (Alterations to NHK Program on Comfort Women: Nakagawa Shōichi and Abe Shinzō Summon Executives on Day Before Broadcast, Say “Content Is Biased”). Shortly thereafter Matsuo Takeshi, a former executive director-general of broadcasting cited in the article as one of the NHK executives, comes forward and flatly denies its content. July: Asahi carries an investigative article on the story, but no facts are revealed that negate Matsuo’s claim. |

| Historical issues | March–April: Anti-Japanese demonstrations spread in China. August: The Roh Moo-hyun administration enacts a law impeaching and ostracizing descendants of Korean collaborators to the Japanese colonial government. | |

| 2006 | Historical issues | August: Prime Minister Koizumi Jun’ichirō makes his last visit to Yasukuni Shrine. |

| 2007 | Comfort women issue | March: The Asian Women’s Fund is dissolved. Prime Minister Abe states that “there was coercion of these women in the broad sense, but not in the narrow sense” and is met by backlash in the West. July: The US House of Representatives passes a resolution urging the Japanese government to apologize on the issue. Yoshida’s testimony is employed as a source. |

| 2010 | Historical issues | September: A collision occurs between a Chinese fishing vessel and the Japan Coast Guard near the Senkaku Islands. Anti-Japanese movements escalate in China. |

| 2011 | Comfort women issue | August: The Constitutional Court of Korea rules the government’s “omission” regarding the comfort women issue as unconstitutional. November: Chongdaehyop erects a comfort woman statue in front of the Japanese embassy in Seoul. |

| 2012 | Historical issues | May: The South Korean Supreme Court rules in favor of individual compensation to Koreans who were forced to perform labor for Japanese firms during the war. August: Korean President Lee Myung-bak visits Takeshima. He also demands that the emperor of Japan apologize to Korea’s independence activists. September: The Japanese government decides to nationalize the Senkaku Islands, sparking anti-Japanese protests in China. |

| 2013 | Comfort women issue | July: A comfort woman statue is erected in Glendale, California, with funding from Korean Americans. |

| Historical issues | March: Park Geun-Hye takes office as president of South Korea. June: President Park visits China as a state guest. | |

| 2014 | Media | August 6: Asahi carries a feature assessing past coverage of the issue of so-called military comfort women and admits that its reports on forced recruitment by the military had been erroneous. |

| Comfort women issue | June: The Japanese government investigates the process by which the Kōno Statement was drafted and decides against revising it. August: Asahi’s assessment articles prompt heightened demands to revise the Kōno Statement, including from within the Liberal Democratic Party. Chief Cabinet Secretary Suga Yoshihide reconfirms the government’s policy that no revision is needed. | |

| Historical issues | January: A memorial hall for An Jung-geun, the Korean nationalist who assassinated former prime minister of Japan and resident-general of Korea Itō Hirobumi, is opened in Harbin, Heilongjiang, China. May: A stone monument in honor of the Korean Liberation Army is unveiled in Xian, Shaanxi, China. July: Chinese President Xi Jinping visits South Korea and remarks to the effect that China and South Korea had joined in a common front in the struggle against Japan. |

Abe Shinzō Asahi Shimbun comfort women Miyazawa Kiichi Kono Statement wartime responsibility Yoshida Seiji Jeju Island forced recruitment,war crime