Rebranding the DPJ: Old Wine in a New Bottle?

Politics- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Seeking to improve their electoral fortunes, the Democratic Party of Japan and Japan Innovation Party merged on March 27. The product of this union, comprising 156 politicians in both houses of the Diet, was christened the Minshintō in Japanese and the Democratic Party in English. But can a new name and a handful of new politicians erase the stigma of the DPJ’s past failure?

With a House of Councillors election in the offing this summer (and rumors circulating of another snap election for the House of Representatives), Japan’s badly fragmented opposition forces, led by the struggling Democratic Party of Japan, recently took a step toward unification in a bid to stop the Liberal Democratic Party juggernaut. As of March 27, Japan’s number one opposition force is the new Democratic Party (Minshintō), formed from the merger of the Democratic Party of Japan and the Japan Innovation Party.

The Opposition’s Perpetual Realignment

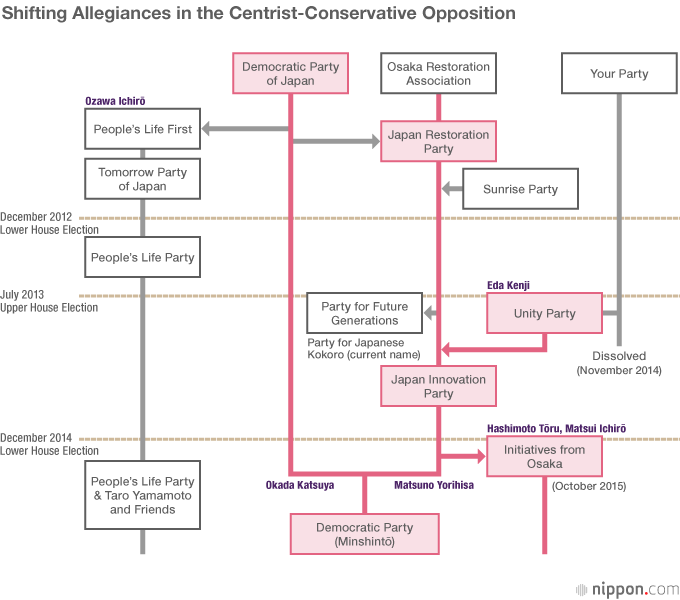

After seizing power from the long-ruling LDP in 2009, the Democratic Party of Japan gradually self-destructed, opening the way for an LDP comeback. On the eve of the DPJ’s crushing defeat in the December 2012 general election, disaffected party members began abandoning ship. One group, led by Matsuno Yorihisa, joined Hashimoto Tōru’s up-and-coming Japan Restoration Party, eyed by many as a dynamic and viable alternative to the DPJ and the LDP—a “third force” in Japanese politics.

But the centrist and conservative opposition resisted unification. Realignment continued for the next three years without yielding a credible opposition force. The past two years have seen the dissolution of Your Party and the fracture of the JIP, formed from Hashimoto’s Japan Restoration Party. The JIP was largely stripped of its political raison d’être when the Osaka faction loyal to Hashimoto split from the party last year.

The DPJ and JIP entered into merger talks in August 2015, but negotiations were interrupted as internecine strife broke out in the JIP. Talks resumed after the Osaka faction split off from the JIP in October, and in December the two parties agreed to form a unified voting block in the House of Representatives. In February 2016, party leaders Okada Katsuya (DPJ) and Matsuno Yorihisa (JIP) signed a memorandum pledging to “aim for launch of a new party by the end of March.” For now, Okada will take the helm as representative. A formal party election will take place after the House of Councillors election this summer.

Strength of Political Groups in the National Diet, March 27, 2016

House of Representatives

| Liberal Democratic Party | 290 |

| Komeitō | 35 |

| Democratic Party (Minshintō), Independents | 96 |

| Japanese Communist Party | 21 |

| Initiatives from Osaka | 14 |

| People's Life Party & Taro Yamamoto and Friends | 2 |

| Social Democratic Party | 2 |

| Independents | 13 |

| Vacancies | 2 |

| Total | 475 |

House of Councillors

| Liberal Democratic Party | 116 |

| Komeitō | 20 |

| Democratic Party (Minshintō), Independents | 64 |

| Japanese Communist Party | 11 |

| Initiatives from Osaka | 7 |

| Assembly to Energize Japan and the Independents | 4 |

| Party for Japanese Kokoro | 4 |

| Social Democratic Party | 3 |

| People's Life Party & Taro Yamamoto and Friends | 3 |

| Independents Club | 2 |

| New Renaissance Party and Group of Independents | 2 |

| Independents | 6 |

| Vacancies | 0 |

| Total | 242 |

Ideological Mash-up

Judging from the unified party platform released by DPJ and JIP leaders prior to the merger, the new opposition party will highlight defense policy and constitutional issues in hopes of capitalizing on public rancor over the security laws pushed through the Diet last year. (The legislation, championed by Prime Minister Abe Shinzō, drew widespread opposition on the grounds that it violated Japan’s pacifist Constitution.) The platform pledges to “staunchly defend constitutionalism, which is the basis of freedom and democracy,” and to maintain an “exclusively defensive military posture,” while at the same time adhering to a “realist” stance in its foreign policy.

On the domestic front, the platform struggles to accommodate both parties’ core policies. It incorporates the DPJ’s focus on improving the lives of middle-class and poor families and on creating “a diverse society where nobody is marginalized.” It also echoes the JIP’s emphasis on “administrative reform, political reform, and devolution of political power.” On energy policy, the platform targets an end to reliance on nuclear power. Its economic policies are an unabashed mash-up, pairing the JIP’s emphasis on deregulation and small government with the DPJ’s commitment to reducing income inequality.

Notwithstanding the focus on upholding the Constitution and maintaining a strictly defensive posture, the platform pledges to “draw up a blueprint for a future-oriented Constitution adapted to such trends as the expansion of human rights and regional sovereignty reform.”

What’s in a Name?

However, the biggest stumbling block to the merger turned out to be the naming of the new party. The DPJ leadership favored the name Rikken Minshutō (Constitutional Democratic Party), while the JIP held out for Minshintō, which combines the min of minshu (democratic) with shin, signifying progress (and recalling the shin of Ishin no To). In an opinion poll conducted by the two parties, Minshintō won the majority of votes, and the DPJ was obliged to yield. But in the English name—Democratic Party—it managed to get the last word.

On the eve of the merger, the JIP had 21 lower house members, almost half of whom had previously belonged to the DPJ. With hopes for Hashimoto’s “third force” in tatters, patching up differences and returning to the mother ship may have seemed like the only practical option.

Seen in this light, the merger may strike voters more as an expedient bid to expand and rebrand the disgraced DPJ than as a substantive step toward realignment and the creation of a meaningful political alternative. Whether a new name and a few new members are enough to overcome the DPJ’s image problems remains very much in question.

(Banner photo: Okada Katsuya (center) and other Minshintō members at the launch of the new party in Tokyo on March 27, 2016. © Jiji.)Democratic Party of Japan Democratic Party Japan Innovation Party