Sapporo Rainbow Pride

Guideto Japan

Travel Gender and Sex- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

A City with a Sense of Direction

I love cities with a grid-like pattern. Kyoto is a perfect example, and so too New York, Xi’an in China, and Mandalay in Myanmar. Walking such cities feels like reading a well-reasoned discourse—there is no chance of getting lost. In ancient times, before we grew accustomed to modern urban life, humans used the sun and moon to ascertain directions for travel. But in well-planned cities, from one fixed point, it is possible to imagine the remainder of the street map. Sapporo is such a city.

The Sōsei River, which flows south to north, divides the city neatly into east and west, while the main road Ōdori splits it into north and south. City blocks are named and numbered logically, spreading out from these axes. Addresses are like coordinates, making it possible to guess a location, and easy to memorize.

Sapporo’s landmark, the 147.2-meter-high TV Tower, is located at the intersection of Sōsei River and Ōdori, acting as a beacon for orientation. One important point to grasp is that the addresses do not refer to street names and intersections, but instead indicate the city blocks.

Ōdori Park viewed from Sapporo TV Tower. (© Li Kotomi)

Mayor’s Words Express Welcome to Sexual Minorities

Sapporo is also noted for the groundbreaking court ruling that forbidding same-sex couples the right to marry violates Japan’s Constitution. If and when same-sex couples in Japan win the right to marry, Sapporo will be remembered for its stand on human rights.

Indeed, this is an inherent quality of the city. Japan’s first pride parade for sexual minorities was held in Tokyo in 1994, but Sapporo staged a similar event just two years later. Tokyo’s parade has been canceled and restarted due to various circumstances over the years, but Sapporo’s has been held more or less continually. Journalist Kitamaru Yūji wrote of his experience at the 2003 Sapporo parade. “I walked with the crowd of participants and headed to Ōdori Park for the closing ceremony, where Sapporo’s then-mayor Ueda Fumio gave a speech. When he uttered the words, ‘The city of Sapporo welcomes all sexual minorities,’ many of those around me suddenly broke into tears.”

After he retired as mayor, Ueda returned to his work as a lawyer and civil activist, and was one member of the legal team which brought the lawsuit for same-sex marriage.

I visited Sapporo to join in the Rainbow Pride in September 2022. Tokyo was still unbearably hot, but Sapporo was refreshingly mild. Pride was scheduled to start on the Saturday, so I arrived the day before.

A City of Gourmands

Whenever I visit a big city, the local lesbian bars are a high priority for me. Unfortunately, there are no such venues in Hakodate or Otaru, but of course there are in Sapporo’s nightlife district Susukino. In Tokyo’s Shinjuku, the nightlife is segregated into different areas: Golden-gai is full of tiny bars, Kabukichō is known for its host bars and sex-oriented entertainment, while Nichōme is home to a plethora of gay and lesbian bars. But all these different scenes exist side by side in Sapporo’s Susukino.

There are two lesbian bars, each with their own distinctive clientele. Bar Orb has cute interior decor, draws a younger crowd, and is often quite lively, whereas Lady’s Bar Lego has a more relaxed atmosphere that appeals to older women. Lego restricts entry to women only, but Orb is a so-called “mixed bar,” meaning admission is open to anyone, although it is mainly patronized by women.

Sapporoites are proud of their food culture. While drinking at Orb, when I mentioned that I was visiting from Tokyo, other patrons goaded me to (over-)indulge in their city’s scrumptious fare. One even recommended me to “gain three kilograms before you go back!” Well-known offerings include soup curry, ramen, and “Genghis Khan” (grilled mutton or lamb). On this trip I was able to try the first two, but sadly not the latter.

Sapporo also has the astonishing tradition of a “shime parfait,” indulging in an American-style ice cream parfait to finish a night out drinking. It is the equivalent of wrapping up with ramen in Tokyo. In Sapporo, the locals head seek out parfait to satisfy this craving. I realized how I might gain weight even on such a short stay.

There seemed no choice but for me to try the shime parfait experience— when in Rome. . . Together with three gay friends, plaintiffs in a same-sex marriage case, I went to a parfait parlor. We arrived at half past ten on Friday night to discover a long line, and waited 40 minutes to get in! Elsewhere, the dessert has a reputation for being popular with young women, but here, half the customers were young men. This cultural fixture knows no gender bias! Fortunately, our group—three older men and one woman—were not too tipsy.

The parfaits were unexpectedly enormous, and rather pricey. At around \2,000, each parfait on the menu was elaborately formulated, composed of copious extravagant ingredients, such as fruits, custard pudding, and even strawberry daifuku. Each was fabulously named: Flying Strawberry Daifuku, Mero Mero, Decorative Drive, Grape Farm #21, just to name a few. They all looked wonderful, but I am a picky eater, and each of them seemed to contain something that I cannot eat.

Sapporo food culture—the amous shime parfait. Left to right: Flying Strawberry Daifuku, Mero Mero, Decorative Drive. (©Li Kotomi)

A Japanese Gender Revolution

Finally the first day of Pride had arrived, with two blocks of the city closed to traffic for the event. The venue had an atmosphere somewhat like a class reunion, and I made the rounds to greet fellow lesbian and transgender activist friends and others. Various LGBT organizations had erected booths to promote their activities, or collect signatures, and some were selling handmade accessories, candles, drink coasters, or other trinkets. Orb had a stall serving alcoholic beverages in the food and drink corner. Recent years have seen increasingly discriminatory discourse targeting LGBT people online. Frequently, uninformed people ridicule LGBT activism as vying for special rights, or chasing after public funds, but a wander around the venue gave a good indication of the grassroots efforts of the groups represented. There was a stage at one end of the area, hosting speakers, panel discussions, and even makeup coaching.

On the evening of day one, I joined a gathering at L-Plaza, home of the Sapporo Center for Gender Equality. The event, which included a panel talk, was attended by many activists who have worked for years promoting LGBT rights across Japan. I was deeply moved as I learned more about the community that had developed over a number of decades. In Tokyo, LGBT activists often attract strange looks and mockery, but a lesbian friend informed me that in Sapporo they are highly respected.

I asked the building personnel and local friends about the building’s name, “Surely it’s not the ‘L’ from ‘lesbian’?” The staff member suggested it was named after the shape of the building’s exterior.

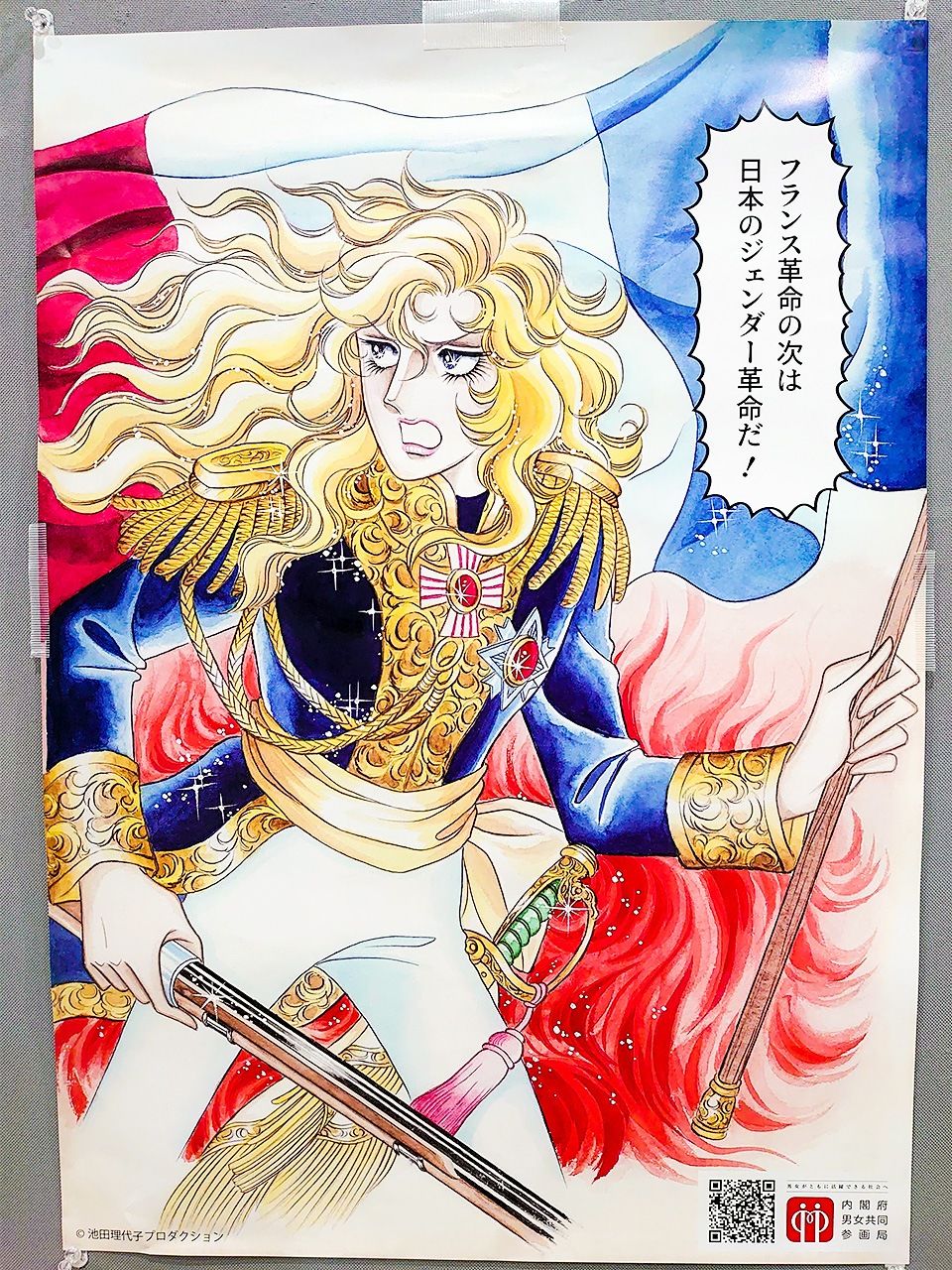

My friend was surprised: “All along I’d assumed it was the ‘L’ in ‘lesbian’.” She works with an NPO called Hokkaido Rainbow Resource Center L-PORT that provides support to members of sexual minorities, and she believes the group’s name is a play on both the building’s name and the word ‘lesbian.’ On one corner of L-Plaza, I saw a poster of the Center for Gender Equality that features a picture from Ikeda Riyoko’s manga La Rose de Versailles bearing the words: “First, the French Revolution, next a Japanese Gender Revolution!” I was impressed by the Sapporo spirit.

La Rose de Versailles poster. (© Li Kotomi)

After this event, I attended a women-only party being held nearby. The venue was in a two-story building, with a DJ playing music on the ground floor, and a quieter bar with seating on the upper floor. It was the birthday of the DJ, a friend of mine, and everyone had planned a surprise for her. The party finished at eleven, after which I walked back with some lesbian friends. It was about two kilometers to our hotel, but the autumn air made it a pleasant stroll. Passing by TV Tower, I felt a pang of jealousy when I noticed a group of young people sitting on the grass in Ōdori Park chatting, seemingly without a care in the world.

Sapporo TV Tower at night. (© Li Kotomi)

Parade Day: Rainy, Clearing Later

The parade was the following day, but unfortunately, it was rainy. Floats in the parade were split into six groups, including some named after Hokkaidō icons: Ezo Squirrel, Salmon, Long-Tailed Tit, Out Japan, Bell System 24, and Northern Fox—my friends and I marched with Salmon.

Sapporo Rainbow Pride is said to be blessed with sunny weather. It is always either a fine day or, even if it starts out rainy, the weather clears during the parade. Today was another such day, with the sun coming out around three in the afternoon. After the parade, I returned to the stage area to catch the performances. An artist was singing a Radwimps song about love. “Even if the world turns its back, you’re still here to fight against it.” A friend close by said to me “I think we’re going to see a rainbow.”

In past years, the event ended with a release of balloons, but with the soaring price of helium this year, the balloons were replaced with bubbles. I was disappointed that I could not see the sky filled with rainbow balloons, but the bubbles had their own charm, and I adored the look on the face of a lesbian friend over 70, who was enthusiastically blowing bubbles.

Bubbles are released after the Sapporo Rainbow Pride 2022. (© Li Kotomi)

On the same day as the parade, I joined a dialog with Kitamaru Yūji at independent bookshop Seesaw Books. I was nervous, as it was my first time to take part in an event in Hokkaidō, but I was pleased with the crowd that gathered. Afterwards, about 10 of the participants held a celebration at Ainu restaurant Kerapirka, an Ainu word meaning “delicious.” It was my first time to try Ainu cuisine, and again, there were many things I could not eat, but I enjoyed that which I could. One of the event attendees was an Ainu musician, who spoke of facing scorn from bigots when trying to express Ainu identity, as though this was being anti-Japanese, or seeking privileges for Ainu people. It reminded me of similar criticisms leveled against Japan’s Korean community—the ruses and spiels employed by bigots seem to follow the same predictable patterns.

In Susukino, the nights are long—after our meal, we continued at another venue, finally calling it a day at half past two in the morning. During my walk back to the hotel, I stopped at Susukino Crossing to admire Sapporo’s downtown bathed in gorgeous neon light.

Susukino Crossing, in downtown Sapporo. (© Li Kotomi)

This was my first visit to the city, and although it was only brief, I can truly say I fell in love with it.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Sapporo Rainbow Pride Parade 2022. © Li Kotomi.)