Breakfast Around Japan: A Culinary Adventure

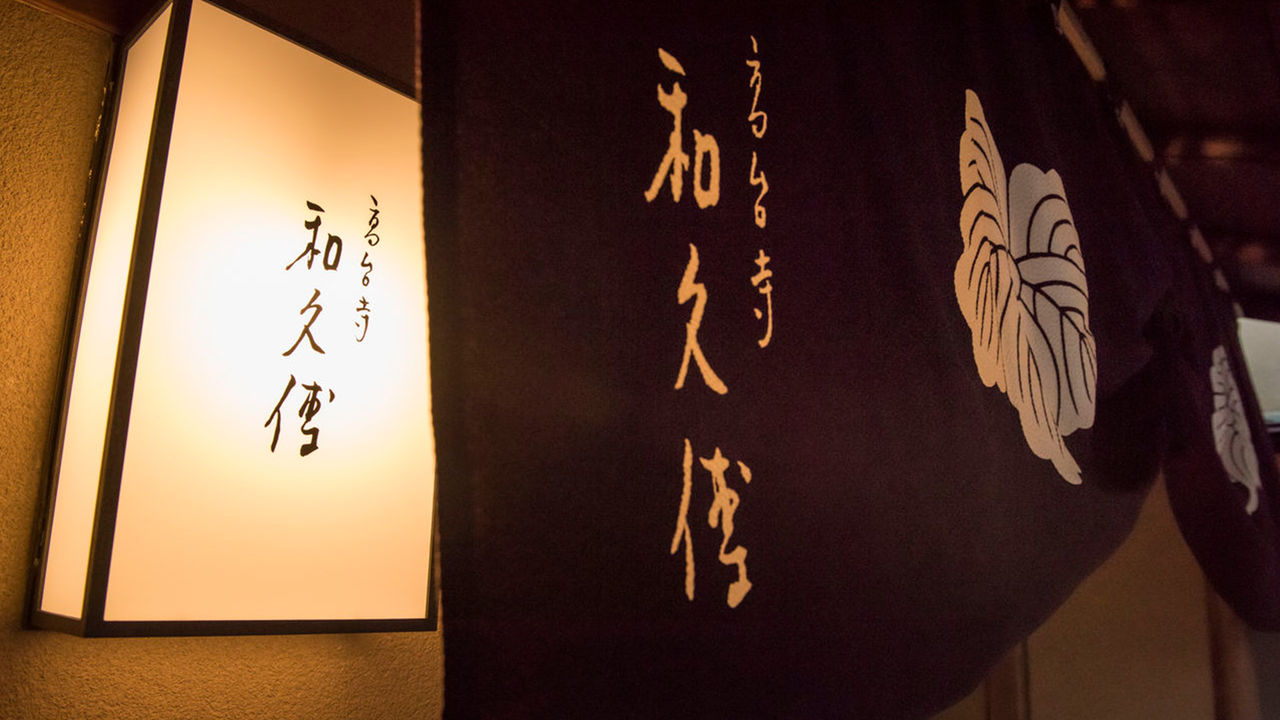

“Ryōtei” Culture Lives at Kyoto’s Kōdaiji Wakuden

Guideto Japan

Food and Drink Lifestyle- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Kuwamura Yūko

Born in 1964 in Kyoto Prefecture. In 1982, after two years at a Zen monastery, she assumed her official duties at Kōdaiji Wakuden, the family business. In 2007, Kuwamura took over as chief executive officer.

The quintessentially Japanese elegance of a ryōtei—the traditional setting for upscale private dining and hospitality—appears to best advantage during the evening hours, like a rare jewel set against black velvet. But the work that goes into polishing that gem begins early in the day.

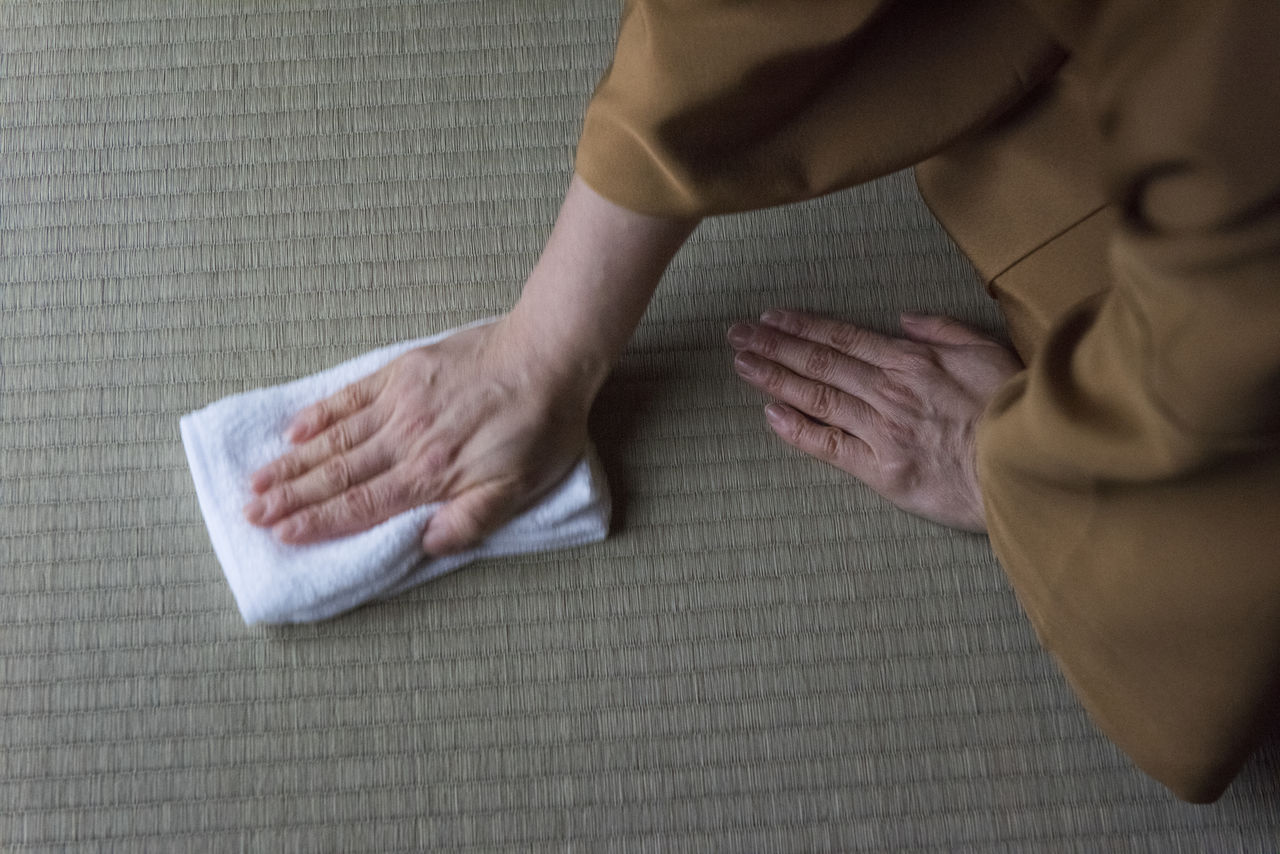

KUWAMURA YŪKO People might find it hard to picture morning at the ryōtei, but it happens to be my favorite time of day. This is when the whole staff comes together as a team to clean the place from top to bottom. We slide open all the shōji doors, even in the dead of winter, and sweep the tatami rooms and corridors until there isn’t a speck of dust. Then we meticulously straighten all the furnishings, right down to the tassels on the floor cushions. We do the same for the garden, wiping dust from each leaf and using tweezers to pick bits of litter out of the moss.

People say to me, “Do you really go to such extremes every single day?” And I say, Yes, every day. This stunning property of ours is Kōdaiji Wakuden’s primary asset, and if we want to make the most of it, we have to begin by keeping it spotlessly clean.

The ryōtei’s quest for perfection begins in the morning, when the entire staff joins in cleaning the building and grounds from top to bottom.

The ryōtei’s quest for perfection begins in the morning, when the entire staff joins in cleaning the building and grounds from top to bottom.

Even the tassels on the floor cushions are carefully groomed.

Even the tassels on the floor cushions are carefully groomed.

The tatami mats are wiped repeatedly with a dry cloth.

The tatami mats are wiped repeatedly with a dry cloth.

Each wooden cross-piece of the shōji must be painstakingly dusted from end to end.

Each wooden cross-piece of the shōji must be painstakingly dusted from end to end.

From Provincial Inn to Kyoto Ryōtei

The neighborhood where Kōdaiji Wakuden is situated, near the center of town, is famous for the “old Kyoto” flavor of its quaint stone-paved streets, as well as such landmarks as Yasaka (Gion) Shrine and Kōdaiji temple, dedicated by Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s wife Nene.

KUWAMURA The property was built in 1952 by Nakamura Sotoji, a master of the sukiya-zukuri [teahouse-inspired] style of domestic architecture. It was originally the home of the head of the Onoe school of Japanese dance. Thanks to family connections, the property passed into our possession in 1982. My mother, Kuwamura Aya, decided to open a ryōtei there. And that was the beginning of Kōdaiji Wakuden.

But the history of our family business goes back further. The original Wakuden, established in 1870, was a restaurant-inn in the town of Mineyama [now the city of Kyōtango] on the Tango Peninsula in the northern part of Kyoto Prefecture. At that time, the district was a thriving center of silk crêpe manufacture. In fact, it continued to prosper until synthetic textiles began to take the place of silk after World War II. As the local industry declined, business at the inn fell off as well. Eventually, it became clear that something had to be done, or the family business would go under, and all its employees with it. That was when my mother made up her mind to open a ryōtei in Kyoto.

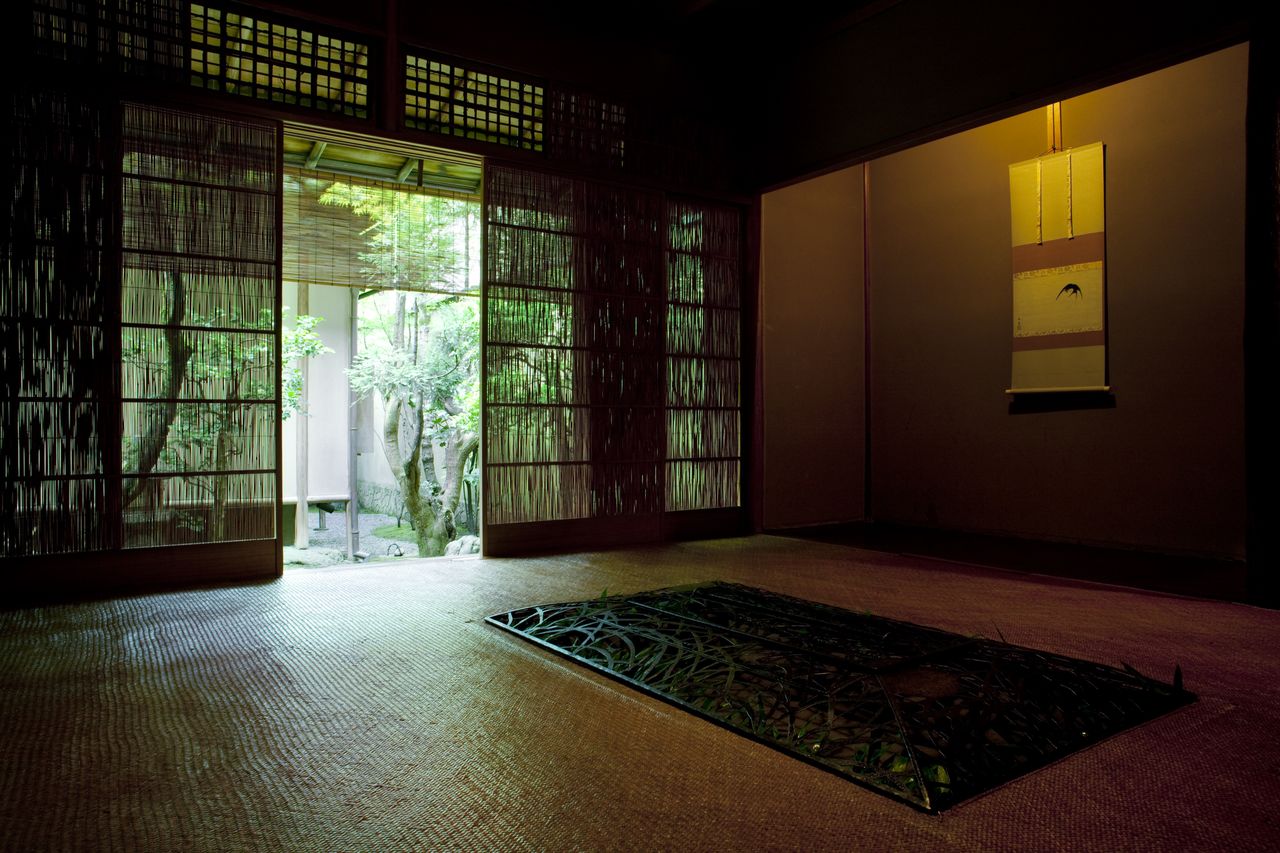

She figured it was hopeless to compete head-to-head with the refined Kyoto cuisine of the city’s established ryōtei. Her idea was to develop our own unique style, drawing inspiration from the flavors of regional homestyle cooking and making the most of fresh local ingredients. She remodeled the interior in keeping with that rural theme. For example, she equipped some of the tatami rooms with irori [traditional sunken hearths], which are used to grill fresh crab harvested from the Sea of Japan. That became one of our trademark dishes. I think my mother had a special genius for striking just the right balance.

Each morning the staff opens the rooms to the surrounding gardens.

Each morning the staff opens the rooms to the surrounding gardens.

A traditional irori hearth forms the centerpiece of this Japanese-style dining room.

A traditional irori hearth forms the centerpiece of this Japanese-style dining room.

The irori dining room in summertime. (© Kōdaiji Wakuden)

The irori dining room in summertime. (© Kōdaiji Wakuden)

The Weight of Generations

The success or failure of a Japanese inn or ryōtei hinges on its day-to-day management, which is usually in the hands of a woman. As the heir apparent to the family business, Kuwamura was expected to pull her weight from an early age.

KUWAMURA In a place like Tango, everyone is expected to help out with the family business, whether it’s a farm, a shop, an inn, or whatever. The biggest share of the work fell to my mother, and the second biggest share fell to me. Family members were treated no differently from employees.

As the only daughter, I realized I would be expected to take over at some point. But I found the prospect daunting; I had no confidence in my ability to direct operations the way my mother did. After I graduated from college, I went to one of the subtemples of Daitokuji and begged them to admit me as a student of Zen.

In a Zen monastery, the day begins and ends with housekeeping. You get up very early and fetch water from the well, dust, and sweep, all before breakfast. At 8:00 in the morning, when the chores are done, you gather for a simple tea ceremony, during which everyone formally greets one another, but prior to that, you never exchange a word.

It seemed to me that one of the key elements of our Zen training was learning to make do with an absolute minimum of speech. We were able to complete virtually all of our daily chores with the help of just three phrases: “Yes [ma’am or sir],” “Thank you,” and “I beg your pardon.” Nonverbal communication took care of the rest.

In the winter, the garden is strewn with pine straw to protect and nourish the moss.

In the winter, the garden is strewn with pine straw to protect and nourish the moss.

The front entrance to Kōdaiji Wakuden. (© Kōdaiji Wakuden)

The front entrance to Kōdaiji Wakuden. (© Kōdaiji Wakuden)

A warm light beckons at the end of the twilit passage that leads through the garden to the entry hall. (© Kōdaiji Wakuden)

A warm light beckons at the end of the twilit passage that leads through the garden to the entry hall. (© Kōdaiji Wakuden)

Zen and the Art of Ryōtei Management

After two years of live-in Zen training at Daitokuji, Kuwamura returned to embrace her official duties at Kōdaiji Wakuden. She helped with the opening of a second restaurant location, Muromachi Wakuden, and was put in charge of direct sales out of the new specialty shop, Murasakino Wakuden. Throughout, she found herself pondering the true source of Wakuden’s brand value.

KUWAMURA I thought about it constantly. The culture of the ryōtei is supported by a large team of professionals. Not just the food but also the ceramic dishes, the building, the garden, the hanging scrolls—all are the work of skilled artisans. And then there’s our serving staff. All the minute details that make up the ryōtei are made possible by the skills these people have honed through years of hard work.

If some of our guests compliment us on a meal, that’s not just the doing of one high-ranking individual. It’s the collective achievement of the kitchen staff, the wait staff, the people who clean and arrange the dining room, and so forth, and none of them can be ranked above the others. Our reputation depends on each team member’s dedication and determination to learn and improve.

So, what’s the ideal toward which we should all be striving? It occurred to me that it was all about creating beauty. I’m not talking about a skin-deep, ornamental sort of beauty. To me, beauty is the sight of a young server hurrying down a short passageway just to get a cup of freshly brewed tea to a guest as quickly as possible, knowing that he has to leave early. So, I guess another way to say it is, the key is each individual’s genuine devotion to hospitality.

Still, abstract concepts like beauty and devotion are probably not enough to ensure the consistently impeccable performance required of a first-rate ryōtei.

KUWAMURA In managing day-to-day operations, I applied many of the lessons I learned during my Zen training. For example, whether at the store or the restaurant, I ask everyone to make the most of those three key phrases: “Yes [ma’am or sir],” “Thank you,” and “I beg your pardon.” I also stress the importance of a thorough cleaning, first and foremost. When all the staff members are doing their utmost to make our space clean and neat, there’s an invigorating sense of teamwork. Also, just as at the Zen temple, when we’re done with all the cleaning, we sit down together for tea. The tea ceremony embodies the standard of beauty that guides all our efforts.

Integrity is another concept to which Kuwamura has given much thought over the years.

KUWAMURA As professionals in the food industry, we get satisfaction from seeing diners’ faces light up when they eat something delicious. But we also need to be aware that their health is in our hands. That’s why people in our position need a strong ethical compass. I call it integrity.

At Kōdaiji Wakuden, letting the ingredients shine is a key culinary principle. This dish accentuates the gelatinous texture for which junsai, an edible water plant, is prized. (© Kōdaiji Wakuden)

At Kōdaiji Wakuden, letting the ingredients shine is a key culinary principle. This dish accentuates the gelatinous texture for which junsai, an edible water plant, is prized. (© Kōdaiji Wakuden)

Giving Back to the Community

Integrity is also a theme in the business’s interaction with the community and its sourcing of produce.

KUWAMURA In 2008, we started processing and packing specialty foods at our new facility in Kyōtango, the family’s ancestral home. The community’s population had been declining for some time, and the site we chose—an abandoned industrial park—was basically a vast wasteland. I wanted to beautify it. So, we planted trees that were native to the area, and over time we turned the site into a park, Wakuden no Mori [Wakuden Forest].

Back when my mother decided to close down Wakuden in Tango, people in the community had begged us not to leave, but there was nothing we could do for them at the time. We had always promised ourselves that, as soon as the Kyoto location was on its feet, we would find a way to give back to the community where we had our roots.

In June 2017, Mori no Naka no Ie, a museum dedicated to illustrator Anno Mitsumasa, opened at Wakuden no Mori. We also opened a new restaurant there, Wakuden Mōri, where we can serve a wider variety of customers.

We’ve converted part of the site into farmland. We grow organic vegetables, which we use at the ryōtei, and we planted fruit-bearing trees, such as sanshō [Japanese pepper]—one of our key ingredients—as well as persimmon, plum, yuzu, and mulberry. We also have a rice paddy nearby, where we plant organic Tango rice every year. That’s the only rice we use.

Wakuden no Mori, in the Kumihama district of Kyōtango.

Wakuden no Mori, in the Kumihama district of Kyōtango.

Architect Andō Tadao designed Mori no Naka no Ie, a museum devoted to the works of painter-illustrator Anno Mitsumasa.

Architect Andō Tadao designed Mori no Naka no Ie, a museum devoted to the works of painter-illustrator Anno Mitsumasa.

The Ryōtei as Culinary Ambassador

Japanese cuisine has gained global recognition, even to the point of being added to UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage list. Kuwamura sees her business as a key point of contact between Japanese culinary culture and the wider world.

KUWAMURA I think there’s this image of the ryōtei as something exclusively Japanese and closed to outsiders. But our kitchen has welcomed chefs from the United States and France who come here to train. Hopefully, we’ll also have some young chefs from the Asian region joining us in the near future.

I like to think of our kitchen as a training ground for the next generation of culinary professionals. Some of Japan’s most highly admired chefs got their start at Wakuden, and I’m quite proud of that fact.

I initially felt a bit nervous about conducting an interview in the formal, etiquette-steeped setting of the ryōtei, but that tension has quickly dissolved. The comforting warmth of the teacup in front of me—repeatedly replaced during the course our conversation—seems to embody Kōdaiji Wakuden’s welcoming ambience.

KUWAMURA It may seem like a small thing, but I’m always stressing the need for careful timing when serving the tea. Each cup needs to be replaced before the tea gets cold, and the freshly brewed tea has to be just the right temperature. I also have my servers bring the tea in a different cup each time, since some of our customers are fans of ceramics and teaware.

It was a customer who introduced me to the saying “Warmth is the sovereign remedy.” Those words left a lasting impression on me. Of course, it’s essential that we maintain high standards in our cooking and our upkeep of the property and so forth. But it’s even more important that we convey a feeling of warmth in the way we go about our work. That’s something I try never to forget.

Wakuden proprietress Kuwamura Yūko.

Wakuden proprietress Kuwamura Yūko.

Kōdaiji Wakuden

Address: 512 Washio-chō, Kōdaiji-kitamonzen, Higashiyama-ku, Kyoto, 605-0072, Kyoto Prefecture

Phone: +81-(0)75-533-3100

Website: http://www.wakuden.jp/ryotei/en/

Wakuden no Mori

Address: 764 Tani, Kumihama-chō, Kyōtango, 629-3559, Kyoto Prefecture

Phone: +81-(0)772-84-9901

Website (in Japanese only): http://www.wakuden.jp/mori/

(Originally published in Japanese on May 1, 2018. Photos by Kusumoto Ryō, except where otherwise noted. Series title written by Kanazawa Shōko.)