Breakfast Around Japan: A Culinary Adventure

Okumura Fumie of Gallery Nichinichi and Tearoom Tōka: Providing a Home for “Handwerk”

Guideto Japan

Lifestyle- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

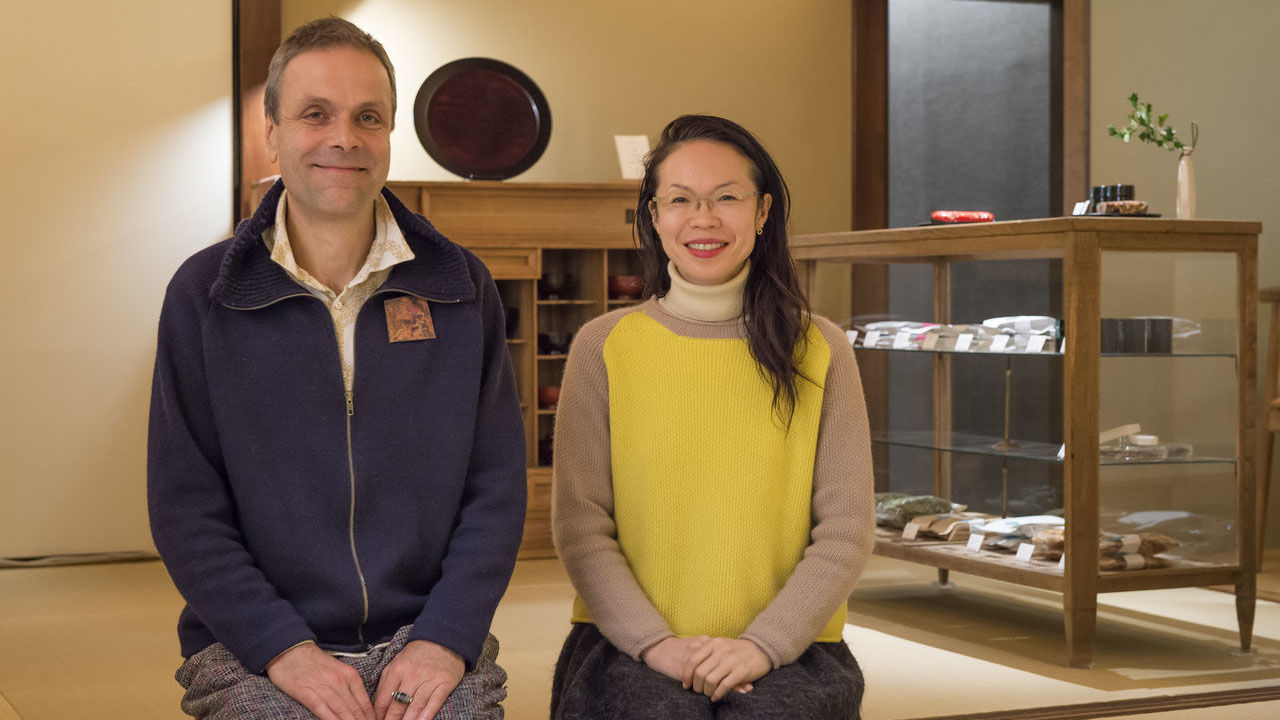

Okumura Fumie

Food design and development consultant. Born in Kyoto Prefecture, raised in Tokyo and Chiba Prefecture. Graduated from Waseda University and worked for Tokyo Design Center before going freelance in 2000. Founded her own company, Foodelco in 2008. In 2016, Okumura and her husband, homeopath and gallery owner Elmar Weinmayr, opened Nichinichi/Tōka, featuring a gallery, tearoom, and “artists’ residence,” in a renovated old Japanese house in Kyoto’s Kamigyō ward.

The custom of tea drinking is firmly rooted in Japanese society, but how many of us take the time to savor fine tea and teawares in an atmosphere of calm and tranquility? At Tearoom Tōka and Gallery Nichinichi, located in a renovated 100-year-old residence just east of the Kyoto Imperial Palace, Okumura Fumie and her husband Elmar Weinmayr have created a clean, elegant, uncluttered space dedicated to quiet communion with fine artisanal tea, food, and handicrafts.

OKUMURA FUMIE I’m a creative consultant working in the medium of food. I’ve been involved in product-development and branding projects aimed at creating new value from the distinctive food cultures of regions and communities around Japan—their rice, their wagashi [traditional Japanese sweets], their local specialties, and so forth.

In 2008, I set up my own independent company, Foodelco, with headquarters in Tokyo’s Hacchōbori neighborhood. But I really wanted to delve more deeply into Japan’s traditional food culture, so in 2015 I decided to move my office to Kyoto.

I came upon this property quite by accident. I wasn’t initially looking for a traditional Japanese house; I’d envisioned something more along the lines of a modern warehouse, something functional. Then one day, a real estate agent sent me some photos of a property up for sale, “just as a point of reference.” And my whole orientation shifted 180 degrees.

It had a beautiful enclosing fence made of naturally finished wooden slats, a traditional genkan [entryway] fitted with a wooden sliding door, and beyond that a spacious tatami room with half-glass shōji [papered lattice doors] looking out onto a Japanese garden and an old storehouse. It was the kind of exquisitely designed and crafted Japanese-style house that you couldn’t build nowadays. In the space of about five minutes, I knew this was what I wanted. That morning, my husband and I had had an argument and were sulking in our rooms, but I immediately rushed out and banged on Elmar’s door, yelling, “Enough, this is no time to be arguing!”

The century-old house was built in the Taishō era [1912–26] for the nihonga painter Nishimura Goun. A masterpiece of Japanese design and construction in its own right, it was not something to be lightly tampered with. Okumura and her husband, Elmar Weinmayr, moved deliberately but swiftly. They began planning the renovations in July 2016 and were able to open Gallery Nichinichi at its new location the following November.

OKUMURA We assembled a crack team of creative professionals that we knew we could trust: architect Futatsumata Kōichi, lighting designer Shōji Hiroyasu, and garden designer Kantō Keisuke. We started off by explaining our basic vision to the team, and then we gradually talked through all the details until we had a plan that matched that vision.

We actually started out by drawing up a comprehensive renovation plan, but in the end we didn’t use it much. The final product was an accretion of ideas that emerged on the site as we went over the property with each of our professionals with the aim of meticulously preserving and restoring the structure’s original design features and functions while limiting our own additions and alterations to a few areas.

Those additions and alterations were the parts that really taxed our ingenuity and creativity. But I think it worked to our advantage that none of us, myself included, were from Kyoto, so we weren’t bound by fixed notions of how things are supposed to be done here.

The renovation plan carefully delineated what was to be modified and what was to be faithfully preserved.

OKUMURA The remodeling involved building a tearoom to the left as you enter the genkan, installing the gallery in the large tatami room on the other side of the genkan, and converting the storehouse into an adjoining living space, the Artist’s Residence. Meanwhile, we made a hard and fast decision to preserve the rest of the design unaltered, including the genkan, walls, corridors, sliding doors, latticework transoms, fixtures, and layout of the main building. Our goal was to preserve and restore the old house faithfully, while furnishing it with new features that reflected our own contemporary sensibility. And we wanted to highlight the distinction between the two.

The ideal that guided us throughout was the masterful restoration and renovation of the Neues Museum in Berlin under the direction of David Chipperfield, who managed to rebuild and modernize the massive nineteenth-century structure without effacing its history or compromising its ambience. Chipperfield visibly incorporated the old building’s war-damaged ruins and made the museum a link between past and future. Elmar and I were deeply inspired by that intelligent approach to renovation.

The entrance to Gallery Nichinichi and Tearoom Tōka.

The entrance to Gallery Nichinichi and Tearoom Tōka.

The gallery occupies the large tatami room on the other side of the genkan.

The gallery occupies the large tatami room on the other side of the genkan.

The elegant simplicity of the interior space accentuates the beauty of the objects on display.

The elegant simplicity of the interior space accentuates the beauty of the objects on display.

Ceramic vases display seasonal plants.

Ceramic vases display seasonal plants.

A Meeting Place for People, Food, and Objects

The project also benefited greatly from Weinmayr’s refined aesthetic sensibility and deep knowledge of Japanese applied arts. Born in Augsburg, Germany, Weinmayr studied philosophy at the University of Augsburg before going to study at Kyoto University under a Monbukagakushō [Japanese government] scholarship. Drawn to the beauty of artisanal handicrafts, such as textiles, lacquer, and ceramics, he opened galleries in Tokyo and Kyoto devoted to the applied arts, with a focus on everyday objects. His Nichinichi Gallery has been in business about two decades.

OKUMURA Elmar’s judgment clearly impressed the Kyoto carpenters and made them approach their work that much more rigorously. It was exciting to see how the house became a kind of medium for communication between creators and artisans, who so seldom talk to one another. I realized then that traditional Japanese houses had a unique power to bring people together.

Elmar had spent years representing artists and artisans from Japan and overseas. Like me, he saw a growing demand for simple, utilitarian beauty—as opposed to ostentatious luxury—in our mature, affluent society. Both of us were searching for new ways to deliver that kind of value to people who could appreciate it.

I had come up against a wall in my work as a food consultant. I wanted to use healthy, organic, sustainably grown ingredients sourced from conscientious small-scale producers. But when you’re working for corporate clients, considerations like that have to take a backseat to your clients’ priorities, meaning profitability and market share. Businesses can’t help being preoccupied with short-term profits, but it seemed to me that the gap between my own personal principles and the reality of my work was getting wider all the time, and the frustration was getting to me.

We wanted to create a space where people would come in search of new discoveries and experiences. We needed a quiet, tranquil place to facilitate that sort of communion between food, people, and objects—not some conveniently located commercial facility.

Epitomizing this quest to facilitate connections, experiences, and discoveries is the Artist’s Residence in the renovated storehouse.

OKUMURA The Artist’s Residence is a way for us to share a space that we consider comfortable, along with the work of our featured artisans, with visiting artists, potential patrons, and others from Japan and overseas, and in so doing cultivate new business opportunities. It occupies the old storehouse and a portion of the main building and features a lounge, workspace, bedroom, and bathroom. The chairs in the lounge afford a view of the moss garden, framed by the half-glass shōji. The main building and the warehouse share a fully-equipped kitchen.

Japanese artisans are very highly regarded the world over, and their work is in great demand. About half the people who come to our gallery are visitors from overseas, and they’re extremely knowledgeable. It may seem a bit grandiose for a small gallery like ours to offer lodgings for artists, but thanks to our great location in Kyoto, we’ve witnessed a lot of unexpected and dynamic interaction. And for us, that interaction is a source of important new ideas.

Kyoto and the Handwerk Tradition

Tearoom Tōka also embodies the ideals of artisanship, with its emphasis on organically grown artisanal teas and handcrafted snacks. The room’s spare, minimalist interior accentuates the beauty of the teawares, the preparation of the tea, and the view of the garden, all integral elements of the tea experience.

OKUMURA The Japanese tea we serve at Tōka is Asamiya tea, grown in the city of Kōka in Shiga Prefecture. Tea cultivation in Asamiya goes all the way back to the seeds that were brought to Japan from China by Saichō [767–822], the founder of Tendai Buddhism. We were visiting a potter in the same area who makes Shigaraki ware, when saw a sign, “Organic Tea Farm.” When we inquired, we discovered that the farmer had been growing tea organically there for more than forty years. He showed us around his field, and it was so lovely and beautifully tended, it did your heart good to gaze on it.

The rice crackers are hand-roasted by a local artisan in his seventies. I met him at a handicraft market held regularly at a Buddhist temple in the neighborhood. I had been looking for homemade okaki to accompany my tea, and his were so delicious that I immediately asked him to roast some expressly for Tearoom Tōka.

As a sweet accompaniment, we offer organic chocolate from Hawaii and fresh Kyoto wagashi [traditional Japanese sweets] prepared the same morning. The combination of chocolate and green tea is a revelation. And, of course, wagashi and green tea are made for each other. The wagashi we serve at Tōka is handcrafted daily at a local family-owned shop, and it varies with the seasons. If you go to the shop early in the morning, you can see the family hard at work in back making fresh wagashi.

This neighborhood is a real mecca for handicrafts and applied arts. We have serious artisans of all kinds—a tatami maker, a metalsmith, and so forth—living and working within a five-minute walk from this house. They all take great pride in their work, and they don’t rely on written contracts; everything hinges on the face-to-face relationships that are still prized in this old, close-knit Kyoto community.

When I first moved to Kyoto, I had a kernel of doubt as to whether I would ever really fit in. I thought it might be hard for an outsider like me to earn recognition in such an established, close-knit community. But then I realized that I don’t need name recognition to take my place as part of this city’s long, unbroken tradition. All I need to do is carry on with my work, quietly and conscientiously, in the knowledge that I’m just a small part of a long history that transcends any single human lifetime. The community sees that and respects it.

The name Tōka (“winter and summer”) is an allusion to tōka seisei (Chinese: dongxia qingqing), a phrase from Zhuangzi comparing inner constancy to the unchanging green of the pine and cypress.

The name Tōka (“winter and summer”) is an allusion to tōka seisei (Chinese: dongxia qingqing), a phrase from Zhuangzi comparing inner constancy to the unchanging green of the pine and cypress.

The counter is made from tochi (Japanese horse chestnut), a high-quality native hardwood.

The counter is made from tochi (Japanese horse chestnut), a high-quality native hardwood.

The lounge of the Artist’s Residence reflects the refined minimalist aesthetic shared by husband and wife.

The lounge of the Artist’s Residence reflects the refined minimalist aesthetic shared by husband and wife.

The furniture embodies their ideal of functional beauty.

The furniture embodies their ideal of functional beauty.

The ceramics and lacquerware are the work of the gallery’s featured artists.

The ceramics and lacquerware are the work of the gallery’s featured artists.

Shared space fosters creative interaction and dialogue.

Shared space fosters creative interaction and dialogue.

Nichinichi/Tōka

Address: 298 Shintomichō, Kamigyō-ku, Kyoto, 602-0875, Kyoto Prefecture

Phone: +81-(0)75-254-7533

Websites: http://www.nichinichi.com/

https://www.tokaseisei.com/

Hours: 10:00 am to 6:00 pm. Closed on Tuesdays.

(Originally written in Japanese. Photos by Kusumoto Ryō.)

Kyoto tourism food Breakfast Around Japan: A Culinary Adventure Kansai tea gallery