The Art of Hamaji Sōshū Comes to Shinjuan’s Sliding Doors

Guideto Japan

- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Painting at the Temple Where He Once Trained

Aside from his creative endeavors, Hamaji Sōshū, both a Japanese-style painter and a bonze, helps out at child welfare facilities. The way his feet are tanned, in the shape of sandal straps, suggest that he may well frequently play in the outdoors with children.

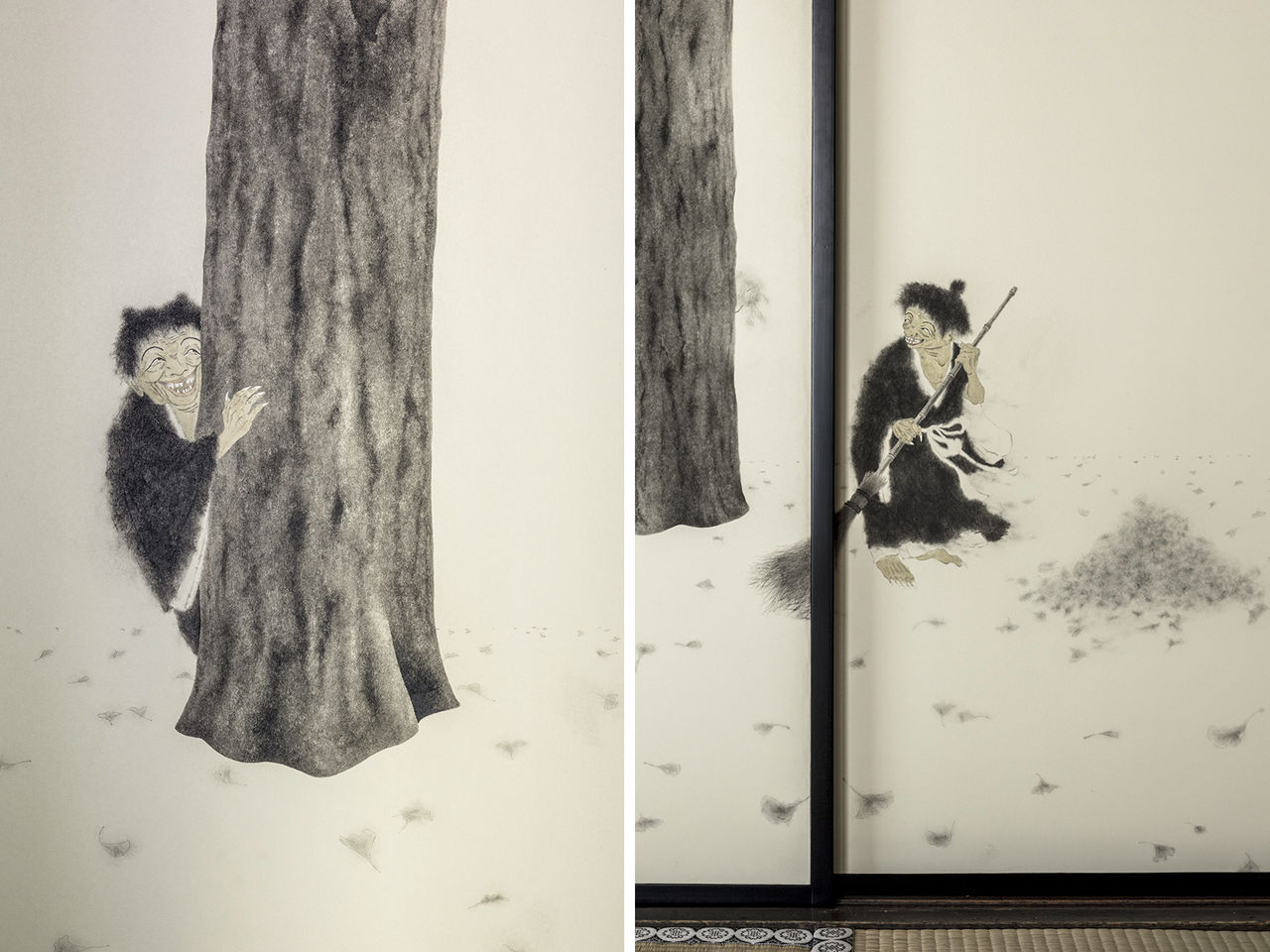

Hamaji’s assignment in this fusuma sliding door painting project is the Ihatsu no Ma, a room to the northeast of the Hōjō Main Hall. On the four fusuma allotted to him, he has painted “Kanzan Jittoku.” While many pieces of poetry are respectively attributed to Kanzan (Hanshan) and Jittoku (Shide), two Chinese Buddhist monks of the Tang Dynasty (618–907), little is known about the particulars of their backgrounds or origins. They have, however, been the subjects of India ink paintings by many artists over centuries, possibly because of the deep impressions made by the stories of their uncommon eccentricities or their strangely appearance, clad only in rags. And they are habitually depicted in these paintings with creepy smiles on their faces. Hamaji says this is the second time he has painted them.

The scene features a great deal of empty space providing the context for four solid-looking gingko trees. Leaves, rendered faintly in contrast to the massiveness of the trunks, drift to the ground. Kanzan peers from behind the leftmost gingko tree, and Jittoku stands by the rightmost, holding a broom made of twigs. Their eyes meet, and they look as though they are up to something.

Upon seeing his work for the first time installed in the Shinjuan Hōjō, Hamaji appeared to be thoroughly absorbed in the impact of his own work. After earning a degree in art at Kyoto Seika University, Hamaji was a resident student at Shinjuan for two and a half years, and it was through this connection that the temple superior asked him to participate in this project.

Kanzan is on the left, Jittoku is on the right. They look at one another with mischievous grins.

Kanzan is on the left, Jittoku is on the right. They look at one another with mischievous grins.

Art Is Self-Expression

I ask Hamaji whether he resided at Shinjuan with the intention of becoming a monk. He replies that he had no such intention whatsoever, and thought only in terms of getting the experience of living in a temple. He spent all his waking time at Shinjuan cleaning the gardens, aside from working just enough to make ends meet.

“I think of nothing at all while cleaning the gardens,” he says. “That sense of detachment, of being in the moment, is like creating.”

When one paints, one invariably tries to engage in an act of mending—of bringing order out of disorder. This interferes with the act of creation, though. When one is engrossed in the act of painting, one encounters moments of being unable to make everything neat and tidy, try as one might. It is the accumulation of such moments that emerges as the work is completed. Hamaji says that he paints pictures on the same themes over and over because it is a way for him to find himself anew in his works. I imagine that Hamaji took on the challenge of this, his second “Kanzan Jittoku,” in the same Shinjuan where he apprenticed, with that purpose in mind.

“Children Have the Knack”

Hamaji says that he is struck by the freewheeling, uninhibited way in which children in the child welfare facilities where he works conduct themselves. It is as if everything in his life leads back to painting pictures. Despite his stated reason for becoming a monk, namely, that he had to experience it to understand it, I imagine that it was also a challenge to himself as an artist.

Hamaji’s fusuma illustrations, with their extensive use of empty space, may seem at a glance to invite observers to take a breather. The mischievous grins on the faces of Kanzan and Jittoku, however, seem to say that it won’t be so easy as all that.

To be absorbed or to be liberated. To confront the challenge or to run away from it. To tidy it up or to let it be. It may be that artist and observer alike share a sense of being told: It’s all up to you.

With its bold use of empty space, this painting seems to be asking us something.

With its bold use of empty space, this painting seems to be asking us something.

Related › New Art in an Old Setting: The Shinjuan Painting Project at Daitokuji, Kyoto

Daitokuji Shinjuan Special Viewing

- Dates: September 1 to December 16, 2018 (closed October 19–21)

- Hours: 9:30 am to 4:00 pm (last entry)

- Fee: Adults ¥1,200, junior high and high school students ¥600, ages 12 and under free (when accompanied by an adult). Note: preschool age children will not be admitted to the Tsūsen’in study or the Teigyokuken tea ceremony room.

- Access: from Kyoto station, take the Kyoto municipal subway Karasuma line to Kitaōji. Transfer there to Kyoto city bus routes 1, 101, 102, 204, 205 or 206 and get off at Daitokuji-mae. From there, 7 minutes on foot (total travel time about 35 minutes).

- Daitokuji Shinjuan special viewing website

- Crowdfunding website for Kyoto Shinjuan (Japanese language only)

(Originally published in Japanese. Photos of fusuma paintings by Asano Satoshi; photos of Hamaji Sōshū by Tsunoda Ryūichi.)