A Basic Guide to Japanese Etiquette

Seasonal Gift Giving in Japan

Guideto Japan

Lifestyle Culture Education- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

From Offerings to Ancestors to Sales Strategy

One facet of gift giving in Japan is the custom of expressing gratitude through midsummer chūgen and yearend seibo gifts to family, relatives, and persons to whom one is indebted. Corporations often draw up lists of their customers and send gifts out en masse, so non-Japanese may be puzzled when such a gift is delivered to their door. The custom has its origins in offerings of fruit or sake to ancestors.

According to proper form, seasonal gifts are handed over in person, with the giver voicing the appropriate seasonal sentiment directly. (© Pixta)

In Japan, there is the ancient custom of welcoming ancestors’ spirits to the home at Obon, which fell on the fifteenth day of the seventh month according to the old lunisolar calendar. Families would gather at home or at the head family’s residence, and neighbors would exchange offerings with one another. In China, this date coincides with the birth of Chūgen, a Taoist deity, when offerings were presented at ceremonies for forgiving misdeeds. The word chūgen was incorporated into Obon-related customs and gradually began to assume the meaning of “gifts as offerings.”

Seibo is rooted in the New Year ceremonies of the Muromachi period (1333–1568). Since families also welcomed ancestors’ spirits into their homes at the new year, relatives and neighbors would gather to bring offerings at the end of the year. In practice, this meant presenting gifts to the elders of the family, with the items then being shared within the family.

These customs changed radically with the advent of the Edo period (1603–1868). At the time, merchants settled their accounts semi-annually, in midsummer and at yearend, and began using the occasion to give gifts to their best customers to thank them for their business. In modern times, department stores launched summer and winter campaigns urging customers to give gifts to people to whom they had been indebted during the year, and the practice of giving gifts to honored teachers, superiors, or business customers spread nationwide.

Department stores’ biggest money-making periods are midsummer and yearend. Here, a department store displays seibo yearend gift items. (© Jiji)

When to Send

Foods—dried noodles, seasonings, fruit, confectionery, beverages, and so forth—are standard summer and winter gift items. Many families will place gifts received at the home’s Buddhist altar first, a holdover from the days when such gifts were offerings to ancestors. Other consumables such as soap or laundry detergent are also popular items, showing the giver’s consideration in sending useful daily goods so as not to impose an undue burden on the recipient.

Sōmen noodles are a standard summer gift. Served chilled and accompanied by condiments, they make a tasty meal in hot weather. (© Pixta)

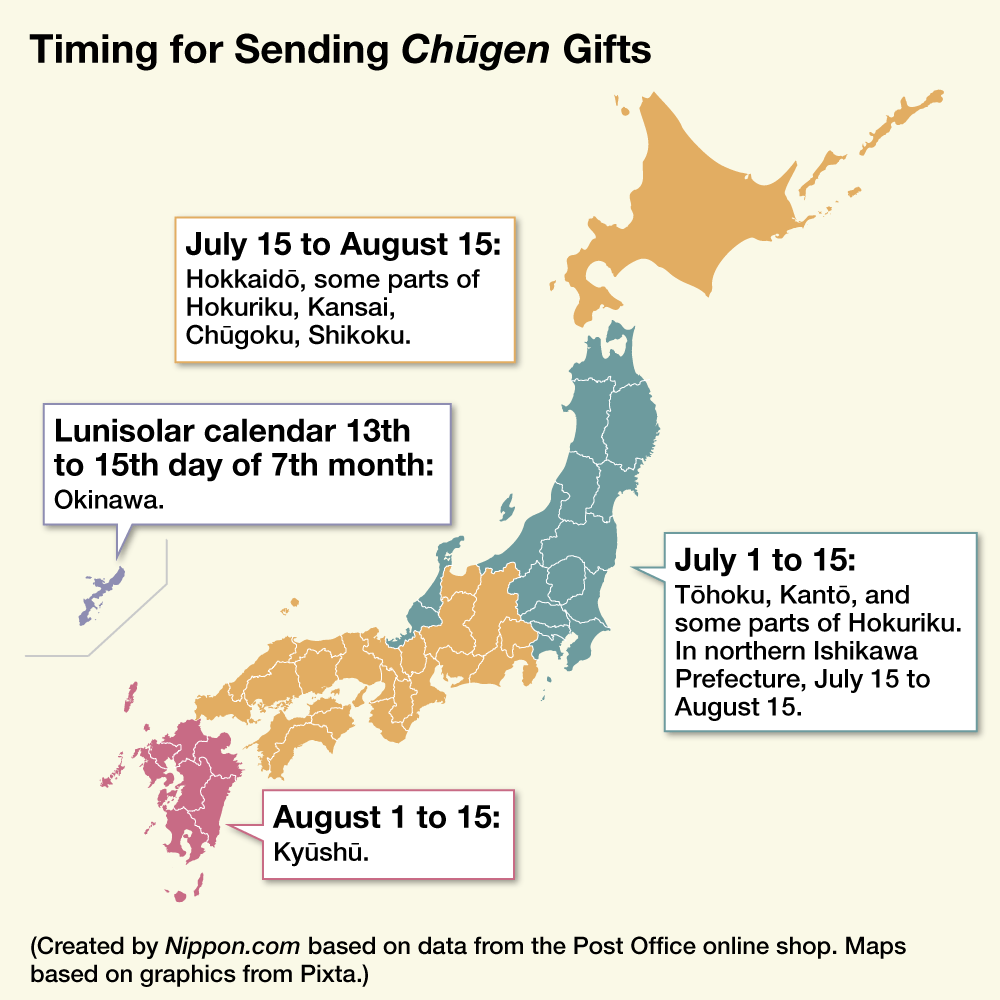

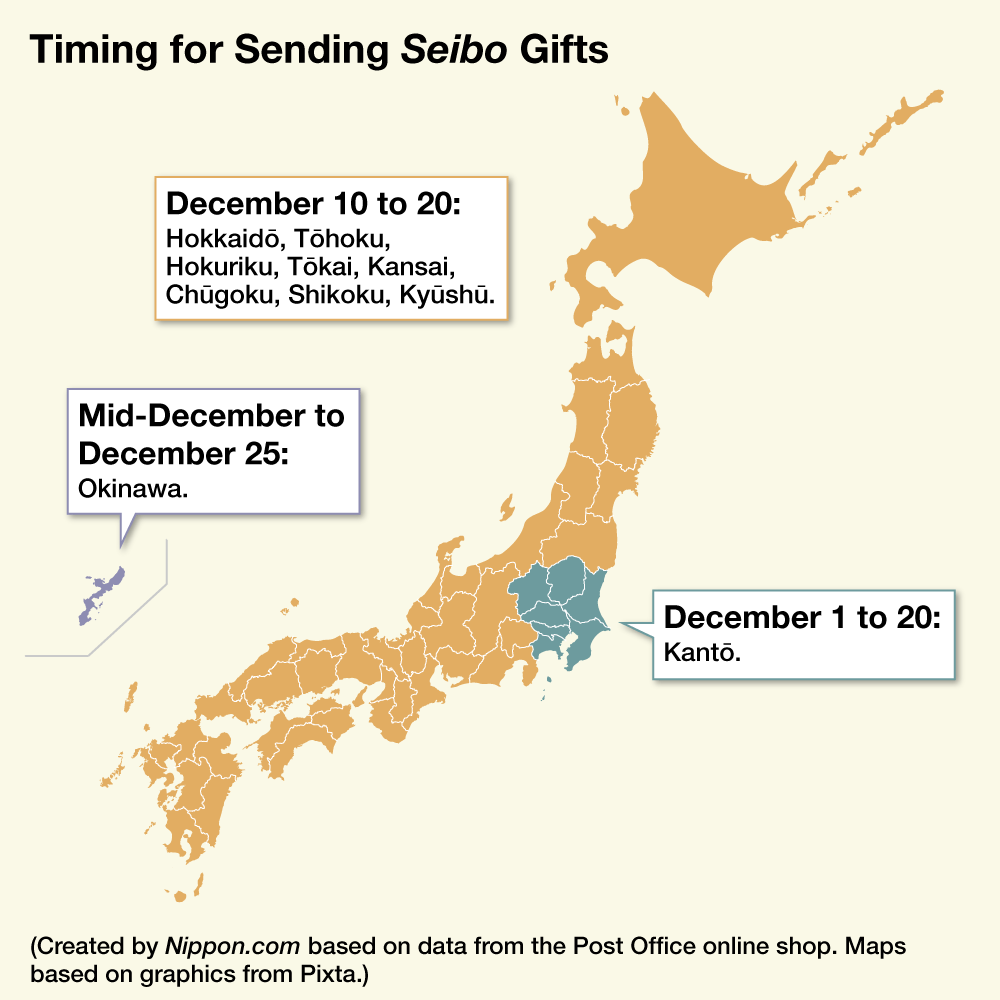

Times for sending chūgen gifts vary widely by region, and if possible, the gift should be sent during the appropriate period. Seibo gifts are generally sent up until mid-December, when everyone begins New Year preparations, but nowadays they are being sent earlier year by year. An exception is fresh foods intended for consumption at New Year’s. These can be sent in late December, but in that case it is best to confirm first whether the recipient plans to be away for the holiday.

If one follows proper form, gifts should be presented in person. Today, however, it is common to send gifts via department stores or mail order vendors. Etiquette recommends that, if possible, the giver send a separate missive notifying the recipient of the gift and expressing gratitude or relaying personal news. If the recommended gift giving period has passed, the message on the gift wrapper should bear the words shochūmimai (summer greetings) or zanshomimai (late summer greetings) in the case of a summer gift, and onenga (New Year greetings) or kanchūmimai (winter greetings) for a winter gift.

Messages after the Chūgen Season Has Passed:

- Shochūmimai : Until around August 7.

- Zanshomimai: Until around September 7.

Messages after the Seibo season has passed:

- Onenga: During the period from January 1 to January 7 (in Kansai, to January 15).

- Kanchūmimai: Until around February 4.

The wrapper on which the message is written is printed with mizuhiki decorative cords and noshi representing an offering of dried abalone, because these traditional symbols express prayers for the recipient’s happiness. The box containing the gift is always impeccably wrapped, a feature of Japan’s gift giving culture. Department stores may use an easy-to-remove wrapper instead, but the careful attention paid to wrapping is the same. Once a gift arrives, the recipient should send a brief letter expressing thanks for the giver’s consideration.

Chūgen and Seibo gifts are wrapped in the noshigami paper used for congratulatory occasions. (© Pixta)

(Originally published in Japanese on November 2, 2025. Supervised by Shibazaki Naoto, associate professor at Gifu University, who specializes in manners education from a psychological perspective, works to guide etiquette educators, and is an instructor in Ogasawara-ryū etiquette. Banner photo © Pixta.)