A Brush with Tradition: Calligraphy Workshops for Tokyo Tourists

Guideto Japan

Culture Japan in Video- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

“The beauty of calligraphy is that it’s a one-time thing,” says Miyazaki Atsushi, who teaches the art in Tokyo. “You’ll never draw the same line again. And each person draws his or her individual lines that nobody else can create. That’s the appeal for me.” Miyazaki mainly instructs Japanese students, but he also has a class for foreign tourists, who are typically complete newcomers to calligraphy. We visited his Shinjuku classroom to see what we could learn.

Geometrical Beauty

After a quick primer on holding the brush at the right angle and keeping a straight wrist, it was time to get drawing. The first stroke to master was a gently rising horizontal line. In calligraphy, the variation in the thickness of lines is what gives them their individuality. This extra dimension adds complexity compared to writing with a pencil. Next came vertical lines, and finally, we were ready to tackle kanji.

In the basic class Miyazaki teaches kaisho, or block-style calligraphy, in which the characters appear similar to how they would as printed text. In more complex styles, it is more difficult to recognize the kanji. The free-flowing and artistic sōsho (cursive) style is particularly hard to read and can even leave Japanese people scratching their heads. As such, kaisho feels appropriate and satisfying for the class.

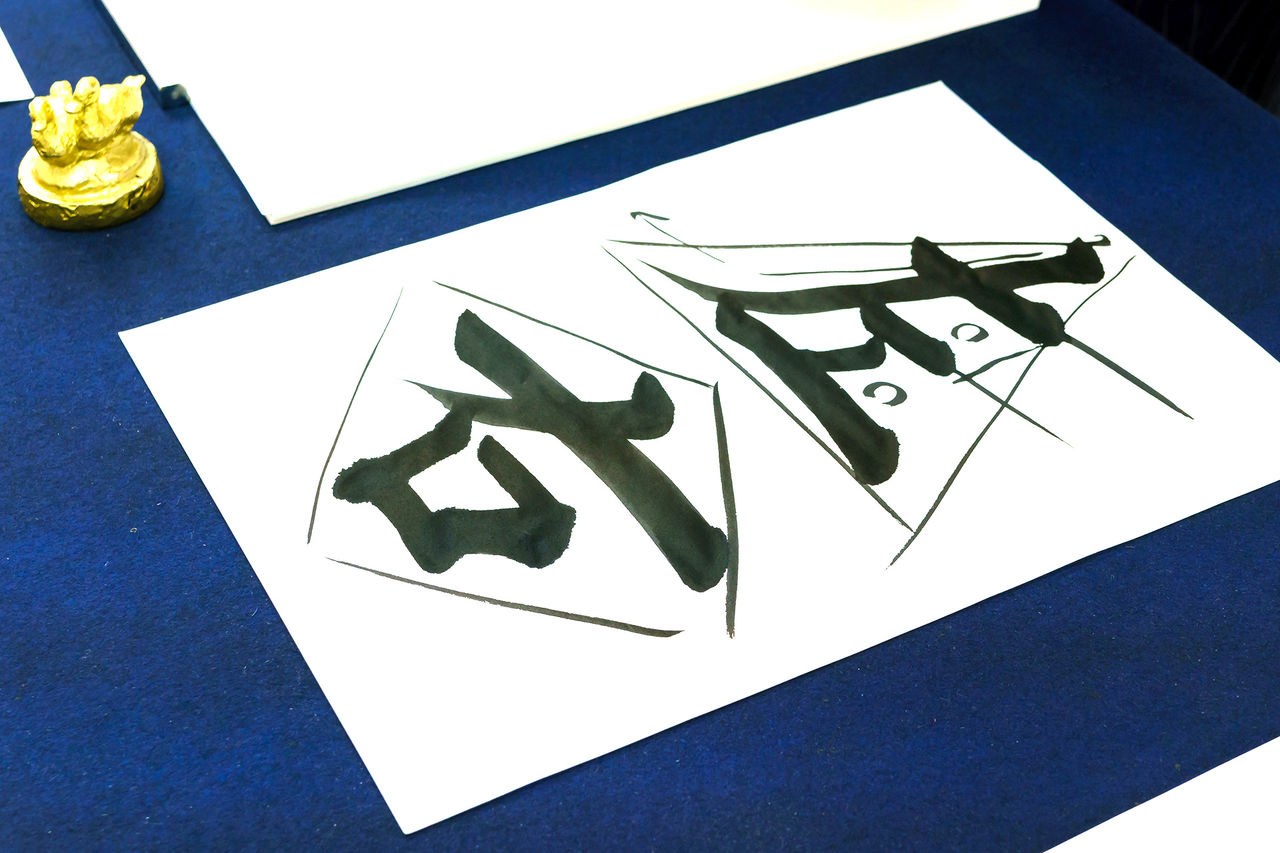

Calligraphy study has its ups and downs.

Calligraphy study has its ups and downs.

The first kanji we attempted were 上 (up) and 下 (down). It was a great chance to deploy our horizontal and vertical lines. The new challenge, however, was to maintain the right balance in the lengths of the lines and the gaps between them. During his explanation, Miyazaki highlighted the geometrical beauty of the characters by drawing a triangle pointing upward around 上 and one pointing down around 下.

The teacher uses geometric shapes to highlight the ideal balance of the kanji: a triangle for 左 (hidari, meaning “left”) and a diamond for 右 (migi, “right”). Additional lines and small circles are guides to appropriate stroke placement and empty spaces.

The teacher uses geometric shapes to highlight the ideal balance of the kanji: a triangle for 左 (hidari, meaning “left”) and a diamond for 右 (migi, “right”). Additional lines and small circles are guides to appropriate stroke placement and empty spaces.

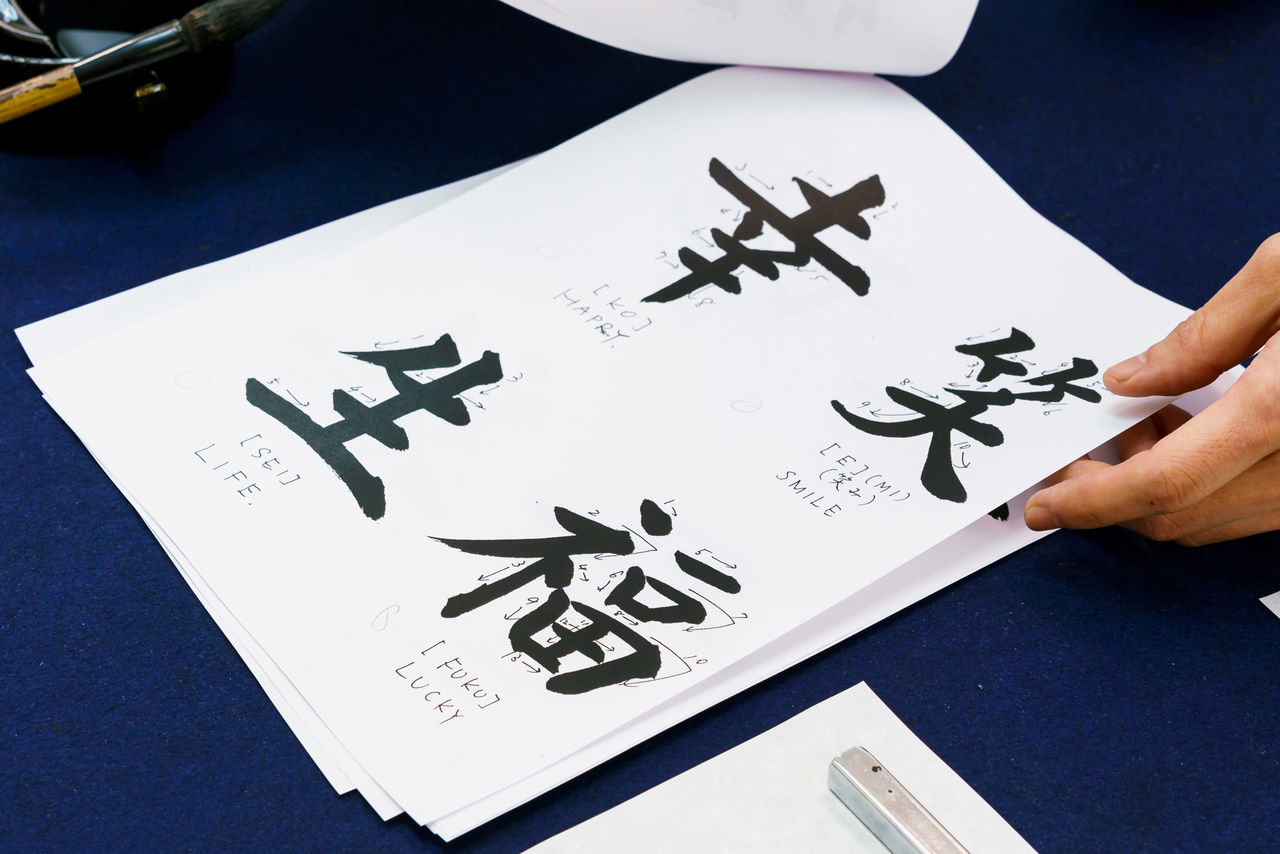

Cats and Foxes

At the end, students choose their own kanji to write on a paper board or fan, depending on the course, and keep as a souvenir. Miyazaki offers suggestions from the practice booklet. When I asked which were most popular, he said that participants tend to choose characters for their meaning rather than their appearance. Kanji like 愛 (ai, “love”) or 福 (fuku, “fortune”) seem appealing, but also difficult, so many opt for 和 (wa, “peace” or “harmony”) instead. He also said 猫 (neko, “cat”) was a common choice, and that he was surprised by how many picked 狐 (kitsune, “fox”).

The class booklet has many kanji suggestions.

The class booklet has many kanji suggestions.

I like the raindrops represented as four short strokes in 雨 (rain), but decided to go for a touch more complexity with 雪 (snow). My final version turned out pleasingly better than I had expected. Miyazaki’s kind and knowledgeable instruction definitely put me at ease during our lesson. As many of the tourists taking the course do not speak Japanese, he teaches in English. He said that most of the foreign students come from North America, Europe, or Australia, although there are sometimes participants from other parts of the world.

Language and Aesthetics

Miyazaki lived in the Czech Republic for four years while studying the Czech language and history of art. His initial interest in Eastern Europe was sparked by the fall of communism in 1989, when the region was constantly in the headlines. During his stay in Prague, he was asked to teach Japanese calligraphy, which he found that many Czechs discovered via the martial art aikidō.

In teaching foreign students, he has encountered many who are left-handed—a characteristic that Japanese youths are often encouraged to suppress, even today. He explained that Japanese calligraphy is more difficult for lefties, especially the kaisho style, but demonstrated that it is possible by lifting the brush with his left hand and drawing a perfect stroke. When I asked whether he was naturally ambidextrous, he said he had just picked it up from teaching so many left-handed students over the years.

Miyazaki gives guidance on improvement using colorful ink that stands out against the black of students’ writing.

Miyazaki gives guidance on improvement using colorful ink that stands out against the black of students’ writing.

Calligraphy is a discipline that combines language with aesthetics. Which does he think plays the larger role? “It really depends on the piece,” Miyazaki said. “Sometimes the literary element is more important and sometimes it’s more about the visual art.”

Japanese Calligraphy Class in Tokyo

English website: http://calligraphytokyo.wixsite.com/calligraphyart

Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/calligraphy.tokyo

Trial lessons available in Shibuya and Shinjuku.

From ¥4,500 for 90 minutes, depending on class and number of participants.

Check the website for full details.

Miyazaki Atsushi

Born in Kyoto in 1979. Associate member of the Sōgen Shodōkai calligraphy organization. Winner of the Mainichi Prize for calligraphers under 23 in 2003. Winner of the Sōgen Shodōkai competition in 2012. Author of a textbook for calligraphy beginners in the Czech Republic.

Miyazaki stands in front of his own work 著 (cho, ichijirushii), meaning “remarkable,” written in the reisho style.

Miyazaki stands in front of his own work 著 (cho, ichijirushii), meaning “remarkable,” written in the reisho style.

(Originally written in English. Photographs and video by Miwa Noriaki.)