Masterpieces at the Foot of the Mountain: Kubota Itchiku’s Kimono Art in Yamanashi Prefecture

Guideto Japan

Art Culture Travel- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Into a World of Elegance

Tourists visiting Lake Kawaguchi, in Yamanashi Prefecture, come for the magnificent views of Mount Fuji to the south. But walking north for around 10 minutes up the gentle slope from the northeastern shore of the lake, they find themselves facing an imposing gate that appears to have been dropped here from another land. This is the entrance to the museum built by Kubota Itchiku (1917–2003), a textile artist who rediscovered a lost silk-dyeing art and added his own genius to make it something all his own—the Itchiku Tsujigahana style of silk dyeing and kimono making.

Itchiku’s aesthetic sense is evident throughout the entire facility and the extensive gardens that surround it. He envisioned this museum, with its decidedly out-of-place foreign atmosphere, as a place not just to showcase the kimonos that were his life work, but also his extensive collection of antiques, objets d’art, stone carvings, and found objects from all around the world that informed and inspired Itchiku’s own creative endeavors throughout his life.

Walk through the front gate, whose front door is an intricately carved wood creation originally used in an Indian palace, and visitors find themselves in the museum grounds. The creeks flowing noisily down the slopes of the 13,000-square-meter expanse are part of the soundtrack that fills their ears as they view the creations and visions of the living national treasure who made the robes they have come to see. The garden is worth a visit on its own, particularly in the autumn—the museum is open every day in October and November—when its colorful leaves paint pictures to rival the kimonos inside.

The main entrance to the museum features a carved wooden door Itchiku bought on a visit to India. Musasabi, Japanese flying squirrels, nest in the branches along the top of its frame.

The expansive garden came largely from Itchiku’s own ideas about how it should appear, but was designed and implemented by Kitayama Yasuo, a celebrated traditional landscape artist from Kyoto.

Amid this garden rise the museum structures themselves. The New Wing presents an unusual face, appearing similar to the Park Güell in Barcelona, Spain, whose terraces were designed by Antonio Gaudi. Indeed, Itchiku, a great Gaudi fan, envisioned this hall as an architectural homage to the Spanish master.

The first floor of this structure, executed in carefully stacked Ryūkyū limestone, houses the museum reception and shop areas. On the second floor is a small hall displaying Itchiku’s prized collection of tonbodama, colorful patterned glass beads that he collected all around the world. These beads, which inspired his creations in dyed silk, include rare treasures—one gold-banded bead from the Mediterranean coast dates back to the first century BCE, while an even older pair are Phoenician specimens from the fifth century BCE. The collection includes vibrantly colored beads from Africa, Asia, and other regions where Itchiku’s artistic interests took him in his searches for inspiration.

The entrance to the New Wing, with its striking limestone pillars.

The bead gallery on the second floor.

At perhaps the dawn of his artistic life, Itchiku, born into a family of antique dealers in Tokyo’s Kanda district, recalled his fascinated exploration as a young boy of his father’s drawer full of tonbodama. After achieving success with his Itchiku Tsujigahana creations, he toured the world to amass his own collection.

Venetian rosetta beads form an elegant necklace (left); the Phoenician beads at right are the oldest in Itchiku’s collection, dating back some 25 centuries.

Innovation with Tradition at Its Heart

Just up the hill from the New Wing stands a quietly imposing wood structure, the museum’s Main Building. Here are housed Itchiku’s finest creations, his Tsujigahana kimonos. Designed as a fitting home for his silk masterpieces, inspired by the natural world and by Mount Fuji in particular, this pyramid is supported by 16 great beams from Aomori Prefecture hiba cypress trees more than a thousand years old.

The Main Building atop its stone foundation.

Visitors’ eyes are drawn first to the sunlight pouring through the glass windows at the pyramid’s apex, and then to the profound beauty of the kimonos illuminated below. Three select robes are displayed on a raised dais at the center of the hall, hung to show their full length of well over two meters. Several dozen more kimonos are arrayed along the four walls.

The exhibit hall is some 200 square meters in area, and is topped by a beam-supported roof 13 meters high at its top point.

Taken as a whole, the hall is breathtaking. From a distance, the robes present seemingly uniform hues—a red one here, a pale blue one there. But as visitors approach a kimono, the astounding depth and complexity of its design pulls them in: Lighter hues set off darkly dyed portions of the image presented, and the three-dimensional topography of the tie-dyed cloth appears more fantastically textured the closer the viewer gets.

Producing this complexity is the Tsujigahana technique that today bears Itchiku’s name. It was once considered a lost technique, but Miyahara Sakuo, director emeritus of the museum, explains that the artist was instantly captivated by its potential when he viewed a scrap of Tsujigahana-dyed cloth in an Ueno museum at the age of 20. He would spend two decades of trial and error, applying his own creative sense of color in his efforts to reestablish the art.

The Tsujigahana technique was created in the Muromachi period (1333–1568). Its basis is tie-dyeing, but it builds on this with painted images, embroidery, the application of gold leaf, and other decorative touches. The luxurious splendor of Tsujigahana kimonos made them a favorite of powerful warlords during the Warring States period (1467–1568). In the early Edo Period (1603–1868), though, Yūzen dyeing techniques appeared, allowing freer artistic expression with greater efficiency in the production process. Tsujigahana artisans faded from the scene and the art died out.

Itchiku was determined to bring Tsujigahana back into the world, but his dream was sidetracked when World War II ended. At the age of 28, he found himself taken to a camp in Siberia, where he would spend six bitterly cold years until the Soviets freed him and he made it safely back to Japan. When he turned 40 he was finally settled in his career and ready to dedicate the remainder of his years to the lost Tsujigahana art.

Years of experimentation followed. It was not until he turned 60 that he was finally confident enough in his works to hold his first solo exhibition. This was the breakout moment for the previously nameless artisan, and the worlds of the kimono and textile arts were soon afire with word of these Itchiku Tsujigahana creations. Interest was high in the United States and Europe as well, and Itchiku achieved a series of overseas shows of his robes. In 1990 he was made a Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres by the French government. In 1995, he became the first living artist featured in a solo exhibition at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington DC.

Robes on display at the museum. At left is the 1991 Ohn (菀), depicting a golden Mount Fuji; Miyahara Sakuo, apprentice to Itchiku, assisted in its creation.

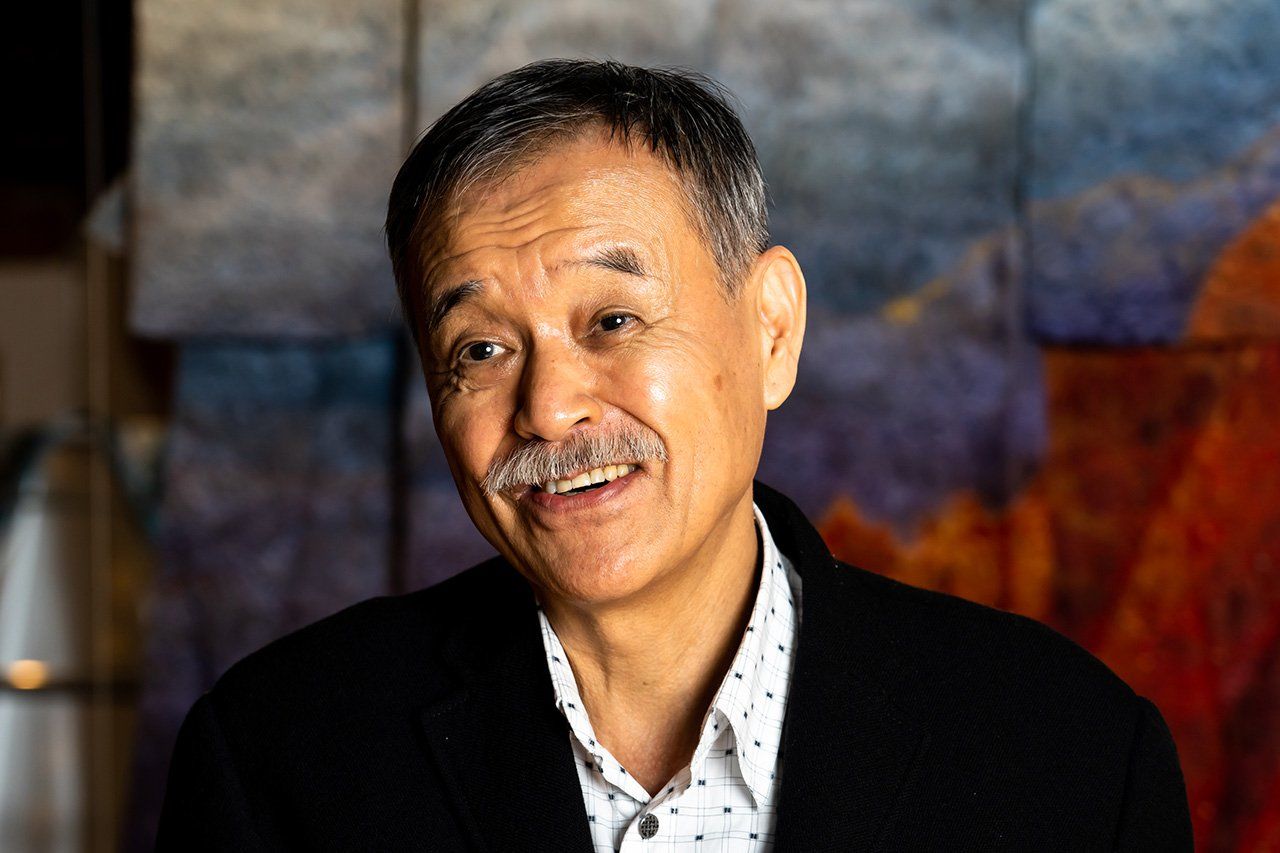

Miyahara Sakuo, now director emeritus of the museum, was for many years the leading apprentice to the master. He explains the Tsujigahana technique: “It uses bold, dynamic compositions and a rich color palette. The puckers left in the material after its shibori ties are removed give it a complicated topography, and embroidery is added to the raised portions to enhance its three-dimensionality and the gradations of its appearance. Set against the rich boldness of the shibori, meanwhile, you have tiny karahana flowers painted with a most delicate touch. The end result is one of the primary characteristics of Tsujigahana, the vastly different views you get of the same work when you observe it from afar and from up close.”

Miyahara worked alongside Itchiku for a quarter-century, right up to the master’s death.

The Itchiku Tsujigahana technique involves sewing the cloth, tying parts of it off, dyeing it, steaming it to set the color, rinsing it in cold water, and removing the ties. This is repeated dozens of times to achieve the desired design.

Itchiku’s technique did not rely solely on the methods and materials of the past, explains Miyahara. “One key point in the development of his art was when he figured out how to use modern chemical dyes, which are notoriously difficult to handle. Unlike traditional plant-based dyes, chemical dyes tend to separate when you try to blend them to make new colors. But Sensei discovered that they could be smoothly blended with the addition of warm water. This made it far easier to control the final colors in the dyed fabric and to apply just the right color to the tied-off portions. This led to the achievement of a color presentation that was all his own.”

On display at the museum are some of Itchiku’s preferred chemical dyes, which he imported from Germany, and the hair brushes he used to apply them.

The Mountain Itchiku Revered

At the age of 70 the creator embarked upon an immensely ambitious project that would be the culmination of his Itchiku Tsujigahana work. This was the Symphony of Light, his envisioned collection of 80 kimonos that would present a vast canvas when placed side by side, containing Japanese scenes from all four seasons, the majestic figure of Mount Fuji above them, and above it all scenes from the cosmos. Sadly, he had only finished 29 of the works when he passed away at age 85, leaving the series incomplete with portions of the mountain in place.

A museum panel shows the final layout of the Symphony of Light, with the finished works in place.

Mount Fuji was a singular motif in Itchiku’s work, especially in his later years. At the root of his fascination was a view he once seen of a red Fuji, explains Miyahara. “Early one morning, as I was driving us somewhere, Sensei and I caught a glimpse of the mountain bathed in the crimson light of the sunrise. From that moment on, he always wanted to see that breathtaking view once again, and we went out any number of times before dawn. But Mount Fuji doesn’t show you the same face twice.”

Itchiku came to view Fuji as a sacred peak, and his infatuation continued until his death. On the shore of Lake Kawaguchi, at the foot of the mountain Itchiku admired, his brilliant kimono creations await new generations of visitors who will view them in a setting that truly does them justice.

When the weather is clear, the café terrace on the New Wing’s second floor offers fine views of Japan’s highest peak.

Itchiku-an, the tearoom at the back of the exhibition space, is a place to enjoy waterfall views along with matcha tea and traditional sweets.

A cave at the top of the hillside garden houses two sculptures Itchiku dedicated to his mother: the Bodhisattva Samantabhadra (Fugen Bosatsu), seated on an elephant, at right and a figure of a woman and child on the left.

(Originally written in Japanese by Kawakatsu Miki. All photos © Miwa Noriaki. Banner photo: Three views of Fuji appear on the kimonos displayed at the center of the exhibition space.)

Itchiku Kubota Art Museum

- Address: 2255 Kawaguchi, Fuji Kawaguchiko, Minamitsuru-gun, Yamanashi Prefecture, 401-0304

- Website: http://www.itchiku-museum.com/museum/

- Multilingual information: Pamphlets available in English, Russian, Chinese, French, and Spanish

- Hours: 9:30 am to 5:30 pm (April–November), 10:00 am to 4:30 pm (December–March); last admissions 30 minutes before closing. Closed on Tuesdays except for national holidays and the first Tuesday in January; closed December 26–29. Open every day in October and November.

- Admission: Adults ¥1,300, high school and university students ¥900, younger students ¥400. The glass bead museum has a separate ¥500 admission fee that includes a drink at the café.