In Lafcadio Hearn’s Footsteps: Connections to Matsue

Guideto Japan

Travel Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

An Admiration of Japanese Culture Is Born

Strolling through the town of Matsue, visitors find themselves confronted with some peculiar names, such as Herun-no-komichi (Hearn Lane), Shimane Breweries Limited Beer Hearn (a craft beer), Karakoro Art Studio, and a park called Karakoro-hiroba The words Herun and Karakoro, which have an amusing ring to Japanese ears, are references to Lafcadio Hearn (1850–1904), a man of letters who resided in Matsue for a time, and who took the alternate name of Koizumi Yakumo when he acquired Japanese citizenship. Writing in elegant English, Hearn contributed to greater understanding, within as well as outside Japan, of Japanese culture, customs, mores, and emotional states, chiefly through such works as Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Things.

Formerly the Matsue Branch of the Bank of Japan, this building now houses the Karakoro Art Studio. Here, visitors can receive guidance and instruction from skilled artisans as they make Matsue-style Japanese snacks and personal articles.

In 1890, Hearn served as an English instructor at Shimane Prefectural Common Middle School. It is reported that the pronunciation of his name was rendered in Japanese at that time as Herun, rather than the more conventional Hān. The pronunciation stuck; he was known thereafter by his students, and eventually throughout the country, as Herun-sensei. Hearn himself apparently approved, and it is also said that Setsu, his wife, referred to his inept use of Japanese as Herun-kotoba, or “Hearn-speak.”

Karakoro, on the other hand, is a Japanese onomatopoeia for the sound that people wearing traditional geta clogs make when crossing the Matsue Bridge, a structure that was still made of wood when Hearn lived there. The association derives from a passage in another volume written by Hearn, Glimpses of Unfamiliar Japan. In this text, Hearn describes the sound of geta on the bridge, which he first heard the morning after his arrival in the town, as unforgettable. The word karakoro has since been appended to names of tourist sites in Matsue, among other places in the town, for having a tonal quality that Hearn was said to be enchanted by.

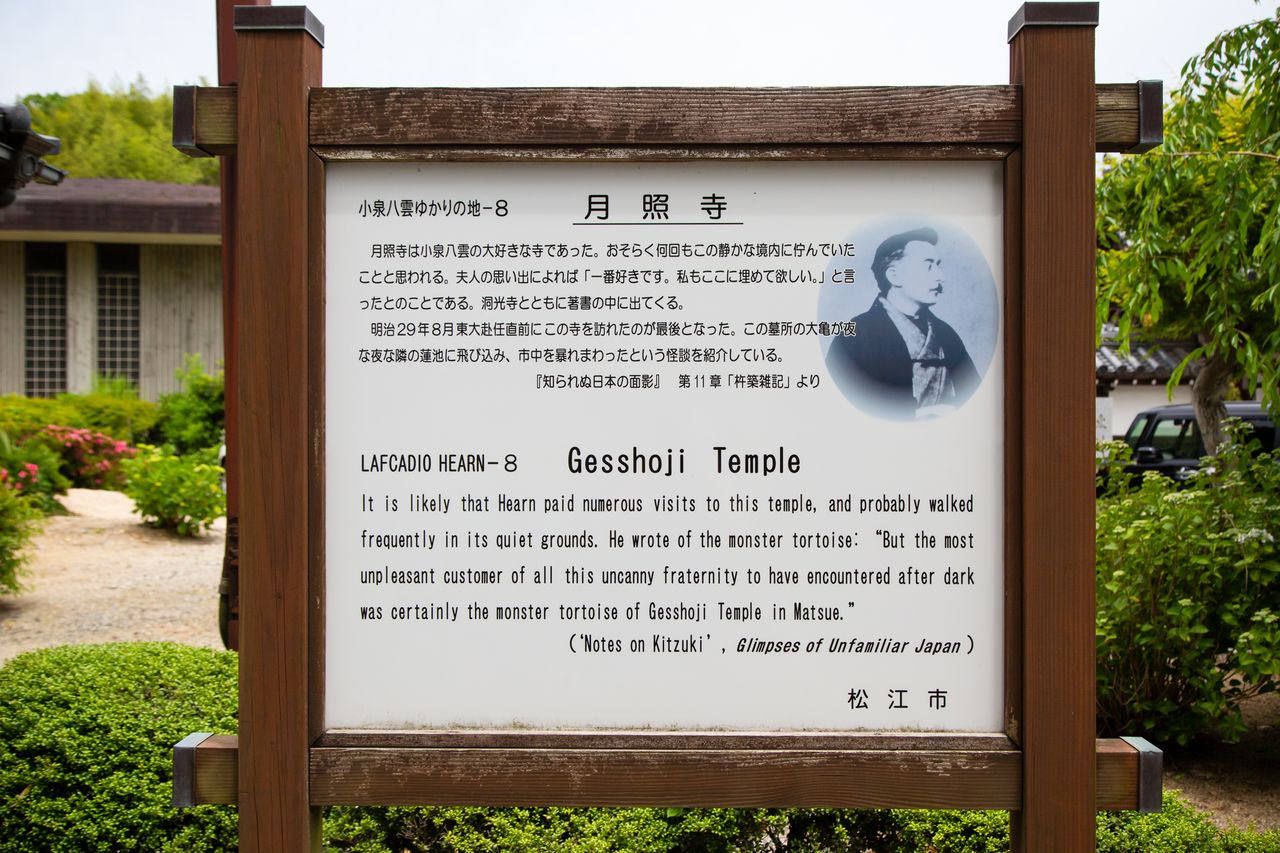

Shintō shrines and Buddhist temples in the area post signs describing their connections to Hearn. His presence makes itself felt everywhere in Matsue, despite his having resided there only briefly. This raises the question of why the local populace took him to its heart so readily.

A sign at the temple Gesshōji describes Hearn’s fondness for the place.

“Lafcadio Hearn resided in Matsue for precisely one year, two months, and 15 days,” explains Koizumi Bon, curator of the Lafcadio Hearn Memorial Museum, and Hearn’s own great-grandson. “While this was the first place where he lived in Japan, one could also call it the shortest stop on his travels here. It is, however, where he met and married Koizumi Setsu, daughter of a Matsue samurai family, and became an admirer of the profundities of Japanese culture. I imagine he would have been stimulated by the spectral, ghost-story-like atmosphere of Matsue, and charmed by the luxuriant natural surroundings of the area. Despite the short time that he was here, strong emotional ties were forged in Matsue as well.”

Reputedly, Hearn’s initial exposure to Japanese culture happened at the New Orleans World’s Fair. Thereafter, in New York, he read an English translation of Kojiki (Records of Ancient Matters), an eighth-century collection of Japanese myth and legend. This provided the impetus for his decision to go to Japan himself. Being especially interested in Japanese mythology, he was apparently delighted at the thought of living in Matsue, for the town is the stage for the tale of Izumo, a myth about the creation of Japan. He found the cold of winter in the San’in region, where Matsue is situated, too much to bear, however, and departed for the warmer climes of Kumamoto. Hearn would subsequently relocate again, first to Kobe and then Tokyo, where he would live out the rest of his days.

Koizumi Bon, great-grandson of Hearn and Setsu, and curator of the Hearn Memorial Museum.

The Museum That Hearn’s Students Built

To the north of Matsue Castle is a road called Shiomi-nawate, where the forms of Matsue as it was when it was a castle town during the Edo period (1868–1912) are noticeably preserved. The lane is lined with structures reminiscent of the dwellings of samurai and other Japanese feudal nobility. At the western end stands the Lafcadio Hearn Memorial Museum. Originally built by the Hearn Society, an association of students of Herun-sensei and others of connections of varying degrees, the museum was donated to Matsue in 1934.

The Lafcadio Hearn Memorial Museum is located at the western end of the Shiomi-nawate road.

“By the time Lafcadio Hearn was lecturing at the University of Tokyo, students who knew him from intermediate school in Matsue once again found themselves studying under him,” says Koizumi. “After he died, they gathered funds, even going so far as to taking up collections from passers-by on the streets, and built the Lafcadio Hearn Memorial Museum here in Matsue. The bonds between Hearn and Matsue are shown to be strong even in terms of the people who were connected to them both.”

Next to the museum is Lafcadio Hearn’s Former Residence, where he and his wife lived for five months. The owner was a founding member of the Hearn Society, and in addition to working on preserving the structure of the house, also provided the land for the museum itself. While the museum, which was renovated in 2016, appears outwardly to still be of a piece with its classic Japanese architectural heritage, the interior has been remade into a series of modern and innovative exhibition rooms.

A relief based on a portrait of Hearn greets visitors. A video presentation and a gift shop are located at the entrance.

The first of these exhibition rooms is chiefly devoted to the experiences and influences that shaped Lafcadio Hearn. Born in Greece and raised in Ireland, Hearn lived an itinerant life, traveling to England, France, the United States, the Caribbean, and at last to Japan, where he lived out his last years. This progression of his life is presented in chronological order. The second exhibition room delves into Hearn’s accomplishments and psychological makeup, organized under such rubrics as journalism and education. The third exhibition room is primarily used for presentations of limited duration.

The unusually shaped walls of the first exhibition room feature easily understood explanatory panels. The display cases on the floor house Hearn’s personal effects, such as travel cases and manuscripts written in his own hand.

Hearn’s belongings are on display throughout the room, together with panels describing the exhibition. These objects include his writing desk and chair, travel cases, kiseru (a traditional Japanese smoking pipe), and scrawls and sketches he made when teaching English to his son, Kazuo. Many of these artifacts were given by the Koizumi family in Tokyo to Hearn’s Matsue students who were reunited with him there, who in turn donated them to the Hearn Society.

“More than 100 articles personally used by Lafcadio Hearn are on display here,” says Koizumi. “Another attraction of this museum is the retelling corner, where Sano Shirō and Yamamoto Kyōji, an actor and a guitarist, respectively, from Matsue, present ghost stories from the San’in region by way of recitations and music. I encourage visitors to see and hear them for themselves, and share the nostalgia for Hearn’s worldview expressed therein.”

The second exhibition room sports a more modernist style. The retelling corner is at left in the photo.

A study where Hearn worked when he lived in Nishi-Ōkubo, Tokyo, is reproduced here with his own personal belongings.

Upon climbing a staircase adorned with photographs of Hearn and his family, visitors find themselves on the second floor. Here there is a library containing works by Hearn and related documents, as well as a multipurpose room that hosts frequent lectures and workshops.

“Foreigners visit here frequently, as well as Japanese,” says Koizumi. “Recently, a researcher from Ireland came here every day for a week, reading nonstop in the library for hours on end. We get a lot of visitors who had never heard of Lafcadio Hearn before, all of whom leave thinking what an interesting person he was.”

This staircase is adorned with rare photographs and artworks inspired by Hearn.

The library is a comfortable place to read. A computerized catalog allows visitors to search for works and other information on the writer and his life.

Lafcadio Hearn Memorial Museum

- Address: 322 Okudani, Matsue, Shimane Prefecture

- Hours: 8:30 am to 6:30 pm April–September (last admission 6:10 pm), 8:30 am to 5:00 pm October–March (last admission 4:40 pm)

- Open year-round

- Admission: Adults ¥400, elementary and junior high school students ¥200. Group discounts and other offers available.

A Garden of Open-Mindedness

The adjoining household is where Lafcadio Hearn moved when he desired to experience the way a samurai would have lived. Upon entering the living room, visitors find a re-creation of the study where Hearn did his reading and writing in this period.

The building is surrounded by a cozy garden that has not been overly touched by human hands; sitting on the deck and looking out over the greenery is a moving experience. It is as if one is in the midst of nature itself, with frogs croaking from the small pond nearby.

Lafcadio Hearn’s Former Residence has been designated a national historical landmark.

The study has been recreated with replicas of the desk and chair used by Hearn. Visitors are welcome to sit and experience being the scholar.

“Feel free to look closely at the garden,” says Koizumi. “Occasionally, there are snakes as well as frogs. Living here caused Hearn to start treating the same frogs and snakes that he abhorred in the West as part of the way of things. He came to intimately comprehend the Japanese view of nature, namely, that people are also part of the natural world. The open-mindedness that led him to embrace various cultures was further refined here.”

Surrounded by the deck, the living room is seemingly at one with the garden.

It was here that Hearn and his wife nurtured their love for each other as well. Many of the ghost stories and folktales that Hearn wrote in his books were told to him by Setsu. As he could not read Japanese all that well, she instead read various documents and texts and told them to him, interspersed with her own opinions and interpretations.

“It is reputed that, although she never got past primary school, Setsu was a literate young lady, very fond of books, who wanted to do more learning,” says Koizumi. “Therefore, I imagine she was quite happy at the prospect of assisting Lafcadio Hearn in his research and creative efforts. When he first heard Setsu’s tellings of these ghost stories, Hearn is said to have been convinced that she was a genuine storyteller, and that she would help him throughout the rest of his life.”

Hearn continued to attend to what Setsu had to say even during his declining years in Tokyo, where he wrote his best-known work, Kwaidan. The tales told to Lafcadio Hearn by this literate young lady born and raised in Matsue had a literary life breathed into them by Hearn’s own English-language renderings of them. He remained connected to Matsue for the rest of his life.

A bust of Hearn erected along the bank of the Hori River, facing the Former Residence, watches over the city of Matsue.

Lafcadio Hearn’s Former Residence

- Address: 315 Kitahori, Matsue, Shimane Prefecture

- Hours: 8:30 am to 6:30 pm April–September (last admission 6:10 pm), 8:30 am to 5 pm October–March (last admission 4:40 pm)

- Open year-round

- Admission: Adults ¥300, foreign visitors, elementary and junior high school students ¥150. Group discounts and other offers available.

(Originally published in Japanese. Reporting, text, and photos by Nippon.com. Banner photo: The first exhibition room at the Lafcadio Hearn Memorial Museum.)