Hotel Chinzansō Tokyo: Exploring Chinzansō‘s Famed Garden

Guideto Japan

Travel History- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Refuge for A Meiji Elder Statesman

Yamagata Aritomo. (Courtesy National Diet Library)

Yamagata Aritomo (1838–1922) was a military man and senior statesman who spent decades at the center of power during the Meiji (1868–1912) and Taishō (1912–26) eras. He was the longest-serving figure among the group of those involved in overthrowing the Tokugawa shogunate in the 1860s, and over his long career he was instrumental in creating Japan’s army and served twice as prime minister.

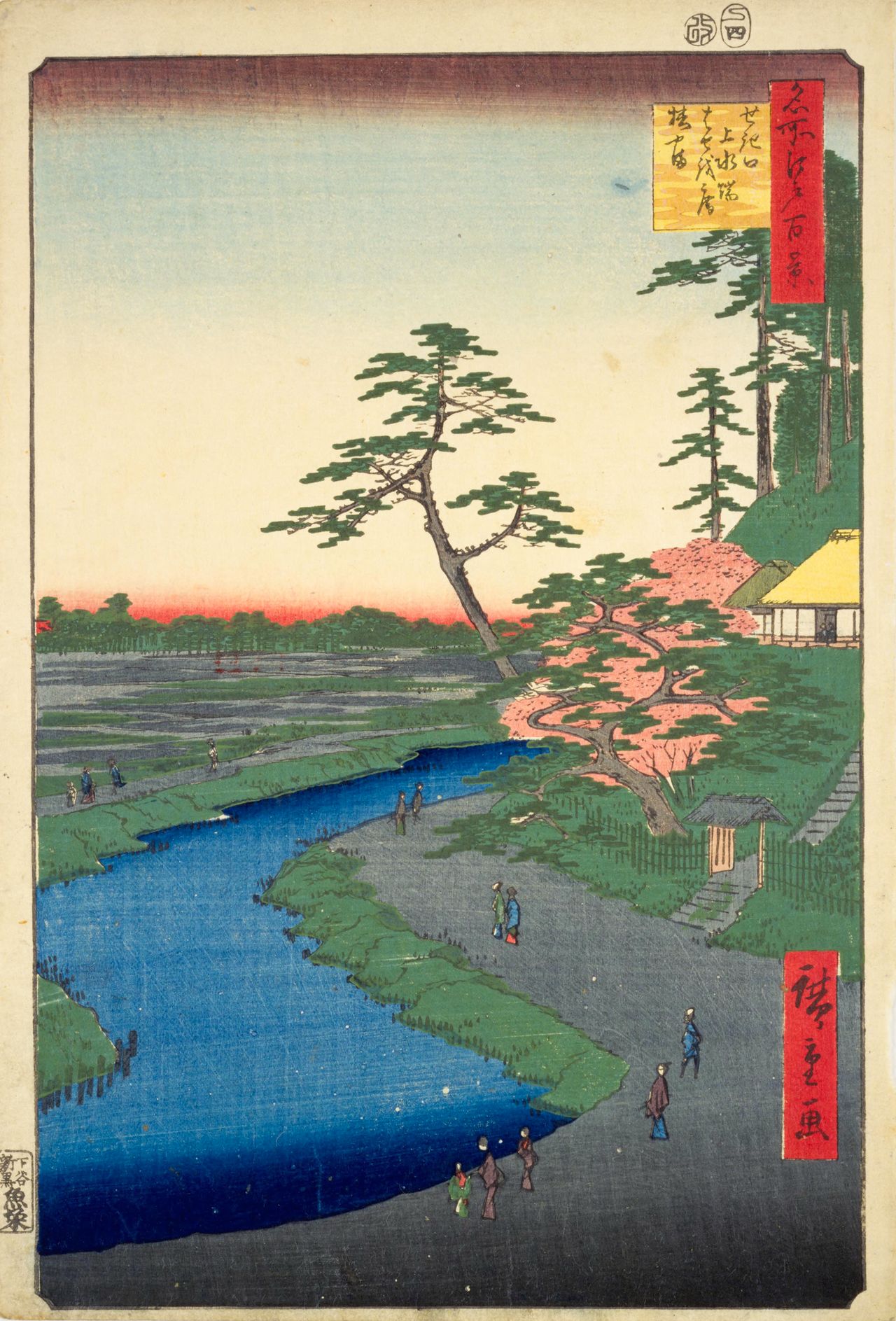

On the eastern edge of the Musashino plains, where much of western Tokyo lies, is the Sekiguchi Plateau, a scenic spot famous for its wild camellias since the fourteenth century. During the Edo period (1603–1868), many daimyō and samurai families had villas in the area, and haiku poet Matsuo Bashō (1644–94) lived nearby for a few years. In the closing years of the Tokugawa shogunate, the ukiyo-e artist Utagawa Hiroshige depicted the area in his One Hundred Famous Views of Edo series of woodblock prints.

“Bashō's Hermitage on Camellia Hill Beside the Aqueduct at Sekiguchi” by Utagawa Hiroshige. The spot near Hotel Chinzansō Tokyo, called Sekiguchi Bashō-an, still exists today. (Courtesy National Diet Library)

A view of the hotel and cherry trees in bloom along the Kanda River, seen in the opposite direction from Hiroshige’s woodblock print.

Yamagata bought the plot of land where Chinzansō stands in 1878 and personally designed the villa and the garden on the grounds. He christened the estate “Chinzansō” after the camellias that grew in the area. The monument in the garden relates how, after peace had settled in the land following the Satsuma Rebellion in 1877, Yamagata had often visited the spot and become enchanted by it; the political and military leader eventually decided to build a retreat there.

The Chinzansō monument, inscribed with writings by Yamagata, is evidence of his great fondness for the place.

Camellias in bloom in the garden at Hotel Chinzansō Tokyo.

Dabbling as he did in composing waka poems, Yamagata had a cultured side evidenced by the passion he devoted to creating gardens. In addition to the Chinzansō garden, he designed a garden at his Murin’an villa in Kyoto and one at Kokian, in Kanagawa Prefecture’s Odawara, where he spent the last years of his life. These gardens are known as the “three great gardens of Yamagata Aritomo.” The closing lines on the Chinzansō monument allude to Yamagata’s hope that those who live there after him will protect nature and enjoy the sights and sounds of that garden as much as he did. From those words, one can gauge the depth of his love for Chinzansō.

The garden is said to reproduce the familiar landscapes of Hagi, the town in present-day Yamaguchi Prefecture where Yamagata was born. It’s not difficult to imagine that Yamagata, who steered the country in various capacities for so long, looked to his garden to find some respite from the pressures of office. For example, Yamagata held Saigō Takamori, a samurai from the Satsuma domain (present-day Kagoshima Prefecture), in high esteem, yet as minister of the army and supreme field commander, Yamagata put down the Satsuma Rebellion led by Saigō, resulting in the latter’s death. And the next year, when he began working to create the garden, Yamagata had to deal with discontent among lower-rank army troops dissatisfied with the reward they were offered for their service. The garden, although situated in Tokyo, must have been a haven for him, a spot that took him back to his native province.

With these thoughts in mind, let’s enjoy a stroll in the Chinzansō garden, a place that meant so much to Yamagata.

The Yūsuichi Pond has been the centerpiece of the garden since Yamagata’s time.

The view from the hotel’s rooftop Serenity Garden overlooks a true urban oasis.

Using the New to Preserve the Old

Okayasu Akira has looked after Chinzansō's garden for the past 40 years. He relates that because the garden was designed following the natural contours of the land, it has many ups and downs and its care requires considerable effort. If the garden had been designed after the hotel was built, maintenance methods and costs would have been taken into account, but in this instance the garden was there first. It incorporates little flat land and the narrow walking paths make it impossible to use motorized vehicles, so almost everything, from saplings to tools, must be carted in and out by hand. But even though Okayasu admits that his job is difficult, his quiet pride in taking care of this historic garden is evident.

“Despite the challenges of the terrain, the various elevations of the garden mean that flowers bloom beautifully in every season and it has year-round charm. During the fall foliage season, the trees in the upper reaches of the garden where the pagoda is located start to color first, waves of crimson gradually descending to the lower levels. The garden also has many different cherry tree varieties, so visitors can enjoy a long sakura-viewing season.”

Okayasu Akira, posing in front of a sacred tree more than 500 years old that escaped the ravages of war.

In 1918, Yamagata passed Chinzansō on to Baron Fujita Heitarō, second head of the Fujita Gumi business conglomerate. Heitarō's father Denzaburō, founder of the Fujita Gumi, was, like Yamagata, a native of Hagi, who got to know Yamagata and others in his circle when he joined the Kiheitai paramilitary organization of which Yamagata was a commander and made his fortune in Osaka in the 1860s onwards. Given this connection, Yamagata believed that Chinzansō, which he had created with his birthplace of Hagi so clearly in mind, would be in good hands with the Fujita family. Fujita Kankō, one of Japan’s leading hospitality companies, which today manages the Hotel Chinzansō Tokyo, is a spin-off from the original Fujita Gumi business conglomerate.

While preserving the garden, Fujita Heitarō dotted the grounds with historical structures from around the country, including the Entsūkaku pagoda, a nearly 700-year-old structure transferred from its original location in Hiroshima Prefecture. But Chinzansō was hit during air raids during World War II, and everything except for the pagoda and a sacred tree burned to the ground. After the war, Ogawa Eiichi, founder of Fujita Kōgyō, the predecessor company to Fujita Kankō, vowed to turn the grounds into an urban oasis for a devastated Tokyo and set to work rebuilding the garden. Alongside this, Ogawa opened the Chinzansō Garden Restaurant in 1952.

Ever since then, Chinzansō has been known throughout the country as one of Tokyo’s most prestigious venues for weddings and parties. A ryōtei traditional Japanese restaurant, a wedding chapel, and various other facilities were added over the years, and the Four Seasons Hotel Chinzansō Tokyo opened on the site in 1992. In 2013, the hotel was renamed Hotel Chinzansō Tokyo when Fujita Kankō assumed management of the property.

The Entsūkaku pagoda, flanked by sakura in bloom, is one of the foremost garden features at Chinzansō.

Forty years ago, when Okayasu began working at Chinzansō, the garden had neither the ryōtei nor the wedding chapel, but structures have proliferated over the ensuing decades as the site grew in scope. “Before I started working here, yearly plans for caring for the garden had been handed down from my predecessors. But new structures on the grounds, from the wedding chapel to the hotel building, changed the available sunlight and prevailing winds. This has affected tree growth and even the development of algae blooms in the pond, so we have had to adapt replanting and pruning methods accordingly. My team and I need to continually come up with new ways to preserve the garden’s appearance.”

The Vent Vert wedding chapel in the garden, with the hotel in the background. The garden is a favorite setting for taking wedding photos, creating a joyous atmosphere visitors can share in.

The tasteful gate to the ryōtei. The bamboo fence along the path, the work of Okayasu and his staff, never fails to charm visitors from abroad.

A Green Spot Ideal for Refreshment

The garden offers enjoyment year-round, featuring camellias that bloom from winter through spring, 120 cherry trees of 20 varieties, fresh greenery in early summer, and colorful leaf displays in autumn. From mid-May to late June, fireflies flit about the garden; in winter, bamboo frames installed to support pine tree boughs against heavy snowfall are a picturesque sight in front of the Entsūkaku pagoda.

“The garden is attractive in every season,” says Okayasu. “In high summer, when few flowers are in bloom, the splashing of the Gojōtaki waterfall and the murmur of the firefly stream provide refreshing sounds that are a pleasant accompaniment to a stroll.” Various stone figures, such as the Seven Lucky Gods, and paintings of Buddhist figures known as rakan (arhats) by Itō Jakuchū (1716–1800), dot the grounds, he explains. Visitors enjoy trying to spot these treasures.

The Gojōtaki waterfall courses over moss-covered rocks. A glass-enclosed corridor behind the waterfall is a popular spot for viewing the garden through the fall’s spray.

A stone figure of Daikokuten, one of the Seven Lucky Gods, associated with wealth and prosperity. Figures of the other lucky gods dot the paths, and many people make a hobby of photographing them.

The garden is also home to many historical artifacts, such as a teahouse and an Inari Shintō shrine designated as cultural properties, kōshintō stone markers associated with a folk faith dating from the seventeenth century, and a 13-story stone pagoda linked with tea master Oda Uraku (1547–1622). Maps detailing the history of Hotel Chinzansō Tokyo and the garden’s artifacts are available for visitors to peruse as they enjoy a stroll.

The garden is open free of charge to hotel guests and to customers of the property’s restaurants, cafés, and lobby lounge. A hotel public relations staffer explains that the hotel holds many special events, from kimono wearing to tea ceremonies, set in the garden to give foreign visitors a taste of Japanese culture. The hotel also arranges garden-related events throughout the year, special dinners at its restaurants and ryōtei, and accommodation plans, all worth checking out.

The sight of fireflies with the red Benkei Bridge in the background creates a magical effect. (Photo courtesy of Chinzansō)

Picture windows in the lobby and lounge of the hotel’s banquet wing frame a fine view of the garden.

Hotel Chinzansō Tokyo

- Address: 2-10-8 Sekiguchi, Bunkyō, Tokyo

- Access: from Tokyo Metro Yūrakuchō Line Edogawabashi Station (10-min. walk) or Tōzai Line Waseda Station (13-min. walk). Also from Tokyo Sakura Tram (Toden Arakawa Line) Waseda Station (8-min. walk).

- Official website: https://www.hotel-chinzanso-tokyo.com/

(Originally published in Japanese. Reporting, text, and photos by Nippon.com.)