Exploring the Osaka Museum of History and the Naniwa-no-miya Historic Site

Guideto Japan

History Travel- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Osaka, Ancient Capital

Osaka is Japan’s third most populous city after Tokyo and Yokohama and the largest municipality in western Japan. It is famous for its role in many major historic events, from the construction of Osaka Castle by Toyotomi Hideyoshi and the Siege of Osaka Castle during the Warring States period (1467–1568) to Japan’s industrial rise in later years. However, few people know that Osaka was also an ancient capital, predating even Kyoto.

The name Naniwa itself, although written with different characters over the ages, has always been associated with the city’s role as a center of waterborne trade. The Yodo River emanating from Lake Biwa and the Yamato River rising in the Nara Basin flow westerly into Osaka Bay on either side of the Uemachi Plateau. Over eons, the rivers deposited sediment, eventually forming a broad delta on which was established Naniwazu, the most important port in ancient times.

The central keep of Osaka Castle at the northern edge of the Uemachi Plateau, photographed from the Osaka Museum of History.

Naniwa-no-miya Park, south of Osaka Castle with a reproduction of the base of the Daigokuden hall in the center.

The site of the Naniwa-no-miya palace, which stood for about 150 years from the sixth to the eighth centuries, lies southwest of Osaka Castle. The remains of the complex were only discovered around 60 years ago, though, which is why Osaka is seldom thought of an ancient capital when in fact it played as prominent a role as Kyoto and Nara in the nation’s early history.

Today, Naniwa-no-miya and the ruins of Hōenzaka, of which Naniwa-no-miya Park is the centerpiece, are a nationally designated historic landmarks. The grounds include the Osaka Museum of History, which relates the history of Osaka from the time of Naniwa-no-miya through its rise as a commercial and cultural center during the Edo period (1603–1868) to its development as the industrial powerhouse of East Asia during the 1920s and 1930s.

The Osaka Museum of History is attached to the building housing national broadcaster NHK’s Osaka headquarters. The thatched roof structure in the foreground is a reproduction of a storehouse from the Hōenzaka ruins.

The Museum stands on a site where Naniwa-no-miya artifacts were found.

A Postwar Discovery

Visitors to the Museum are whisked from the ground floor entrance hall to the tenth floor by elevator. From there, they ride an escalator down floor by floor to view exhibits detailing Osaka’s history over the centuries.

On the tenth floor, a diorama depicts the massive Daigokuden hall as it looked in 744, during the latter years of Naniwa-no-miya. Amid a row of life-size vermillion pillars, attendants stand in a great room with an elegantly decorated ceiling.

A full-size reproduction of a ceremony at the Daigokuden, a structure supported by pillars 70 centimeters in diameter.

Figures representing the emperor’s attendants are clad in colorful garments.

An unobstructed view of Naniwa-no-miya Park in the heart of the city.

Naniwa-no-miya was the imperial capital at two different times in Japanese history. The first occasion was when the capital was relocated to Naniwa rom Asuka in Nara in 645 by emperor Kōtoku (r. 645–654). A decade later, the capital was moved back to Asuka, but emperor Tenmu (r. 673–86) adopted a two-capital system, with Naniwa being the other political center. During the Nara period (710–94), emperor Shōmu (r. 724–49) made Naniwa the secondary capital and rebuilt the Naniwa palace, which had burned down. However, the imperial court resided at Naniwa for just one year starting in 744.

Although Naniwa-no-miya is mentioned in the Nihon Shoki, a record of classical history completed in 720, its exact location and the layout of its buildings had long been a mystery. After World War II, Yamane Tokutarō, formerly a professor at Osaka City University, began excavating at Hōenzaka and discovered the ruins of the Daigokuden there in 1961. At the Osaka Museum of History, visitors can learn about this long-lost part of Osaka’s past.

A display showing artifacts and documentation relating to the excavation of Naniwa-no-miya. In the center is a reproduction of the complex during its first period as the center of the imperial court.

A diorama gives an idea of the grand scale of Naniwa-no-miya the second time it became the capital.

Making History Again

The ninth floor exhibit showcases Osaka’s history in the middle ages and early modern era. During the Warring States period, the fortified temple complex of Osaka (Ishiyama) Honganji, head temple of the Jōdo Shinshū (True Pure Land) school of Buddhism, occupied the northern edge of the Uemachi Plateau. It was around that time that the name Osaka began to be used.

Warlord Oda Nobunaga, who wished to establish control over western Japan, attempted to wrest the land from Honganji to build a castle on the site. But the temple resisted, leading to a standoff that lasted from 1570 to 1580. The temple finally ceded the site and moved to Kyoto, although Nobunaga was assassinated before he could build the castle, which was ultimately erected by his successor, Toyotomi Hideyoshi.

A scale model of Osaka Honganji’s Mieidō Hall, with a faithful reproduction of the town at the temple’s gates.

Hideyoshi began building Osaka Castle in 1583, gradually expanding its scale, and drew up the basic plan for the city’s layout, a legacy that has lasted to this day. In 1615, the recently established Tokugawa shogunate eliminated the Toyotomi clan with victory at the Siege of Osaka Castle and placed the city under its direct control. The government oversaw the excavation of a network of waterways which contributed to the development of water transport and helped the Osaka flourish as a center of commerce and industry. Rice paid as tax was shipped to Osaka from all over the country, giving it the name “the kitchen of the nation.” From the second half of the seventeenth century to the early eighteenth century, Osaka also gave birth to a culture supported mainly by the wealthy merchant class, thanks to which arts like kabuki and ningyō jōruri puppet theater developed.

A lifelike exhibit demonstrating how Osaka prospered during the Edo period thanks to water transport.

A diorama showing Senba, the heart of Osaka, and the many playhouses clustered there. A danjiri festival float dating from the Edo period is displayed nearby.

Bigger than Tokyo

The last of the permanent exhibits, on the seventh floor, details the history of modern-day Osaka.

The city continued to develop as a center of commerce and industry in the Meiji era (1868–1912) and its population grew rapidly, especially after the Great Kantō Earthquake of 1923, when many residents of Tokyo and Yokohama migrated there. By the mid-1920s, the city had expanded by incorporating neighboring towns and villages, and its population of 2,110,000 had overtaken that of Tokyo, making it Japan’s largest city. This was the golden age of “Great Osaka,” whose population had grown to 3.3 million, exceeding the present-day population of 2.7 million, by the early 1940s.

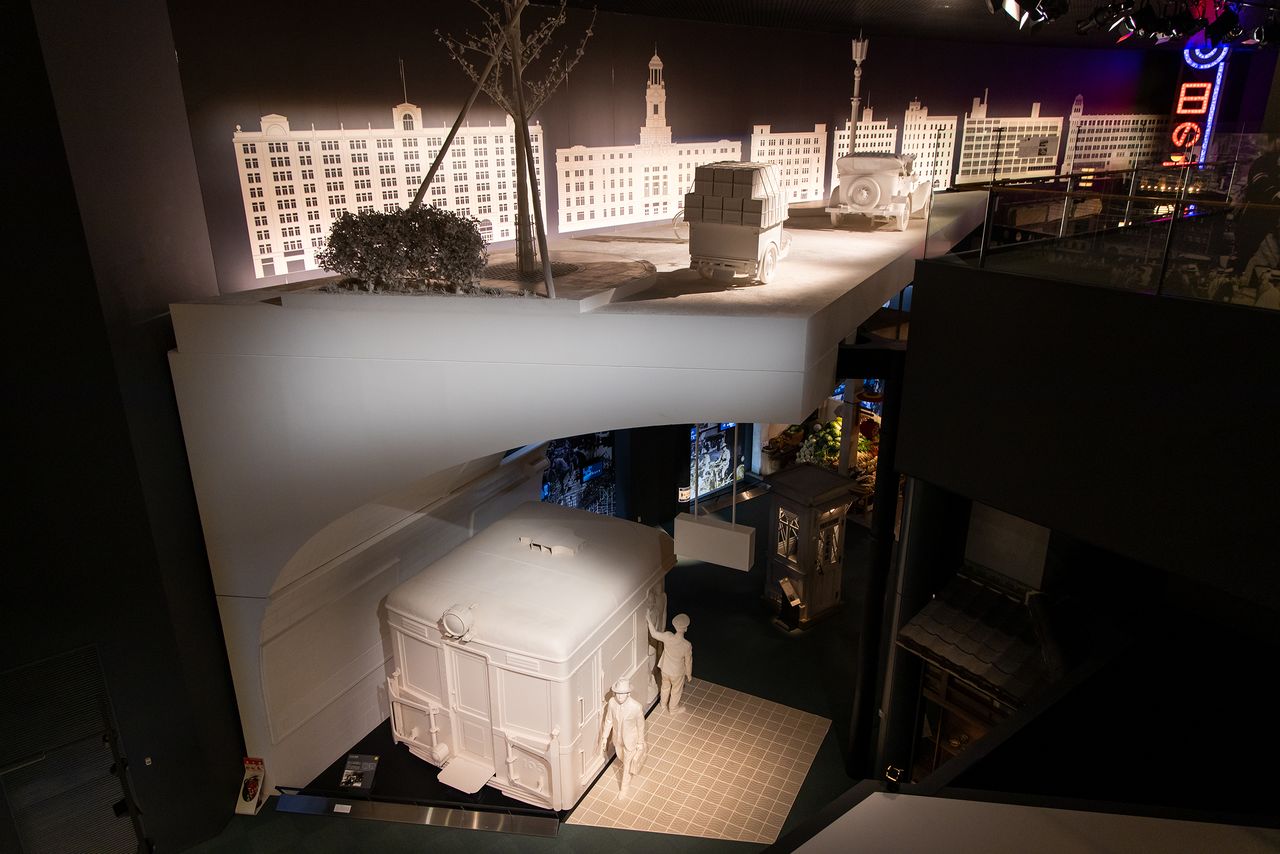

The seventh floor “Great Osaka” display viewed from the eighth floor. In the center is a life-size reproduction of Japan’s first public subway line. The area also features special exhibits and a hands-on archaeology section.

Lifelike reproductions of Osaka sites Shinsaibashisuji, Dōtonbori, and the Honjō public market.

World War II bombings left central Osaka a charred ruin, but the city made an amazing recovery, going on to host the 1970 Osaka Expo, symbolic of Japan’s postwar high-growth period. Osaka will once again host an international exposition, the Osaka-Kansai Expo, in 2025, and the Osaka Museum of History invites visitors to learn how Osaka developed over 12 centuries to modern times.

Lifelike reproductions of Osaka sites Shinsaibashisuji, Dōtonbori, and the Honjō public market.

Osaka Museum of History

- Address: 4-1-32 Ōtemae, Chūō-ku, Osaka

- Hours: 9:30 am to 5:00 pm (last entry 30 minutes before closing time)

- Closed Tuesdays and December 28–January 4

- Admission to the permanent exhibit: Adults ¥600, high school and university students ¥400, 15 and under free; group and other special rates available

- Getting there: 3 minutes on foot from Tanimachi 4-chōme Station on the Osaka Metro Tanimachi and Chūō Lines

(Originally published in Japanese. Reporting, text, and photos by Nippon.com.)