Japan’s Growth Strategy for a New Era

The Tokyo Waterworks Take On the Global Market

Economy- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Supplying Water to 13 Million Tokyoites

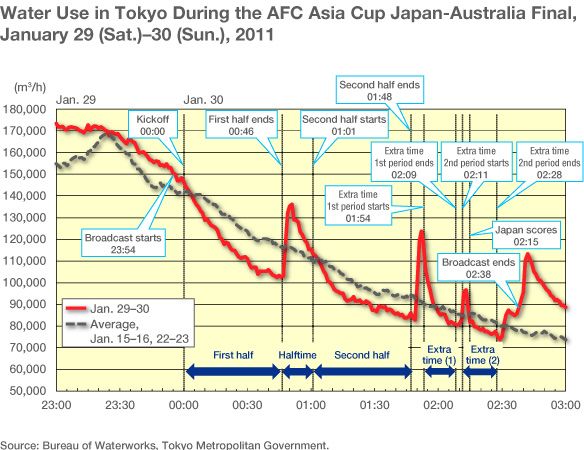

The demand for water, like electricity, has peaks and troughs. Sometimes it fluctuates dramatically in a short period of time. This happened, for example, in the wee hours of January 30, 2011, from around midnight to three o’clock in the morning. Usually water demand in Tokyo tapers off steadily during these midnight hours, but on that day it surged repeatedly. The reason was that Japan and Australia were playing in the final match of the AFC (Asian Football Confederation) Asia Cup soccer championship in Qatar and the match was being broadcast live on Japanese television.

As shown in the attached graph, water use fell sharply after midnight, when the match started. Viewers were glued to their TV sets, with no thought of getting up to use water. But immediately after the end of the first half, the flow jumped to a rate of almost 30,000 cubic meters an hour over a period of just a few minutes. One can easily guess what happened: Many of the viewers took this chance to use their toilets. The match ended with a victory for Japan after extra time, and there was another big spike at the end of the second half, followed by a smaller one between the two periods of extra time and another big one after the end of the broadcast. This final peak presumably came as people bathed while thinking happily about the victory or had drinks to celebrate.

Everybody who headed to the lavatory during halftime took it for granted that the toilet would flush for them. In fact, however, this is far from a matter of course. Events like the live broadcast of this crucial international soccer match are not common, but even at times other than such “emergencies,” the supply of water is constantly being adjusted to match users’ constantly changing needs. Without this sort of ongoing adjustment, the matter-of-course flow of water would not be possible to maintain.

The Bureau of Waterworks of the Tokyo Metropolitan Government supplies water to about 13 million users. The Tokyo Waterworks are thus one of the biggest unitary water supply systems in the world. The total length of the waterworks’ underground pipes is equivalent to half the earth’s circumference. These pipes are spread throughout the Tokyo Metropolis like blood vessels, branching out from the main arteries to capillary-like water pipes leading to users’ premises. Unless the pumps are working properly, this water will not make it all the way to its destination. And if the pressure is too high for the current level of use, pipes are liable to burst.

A Pair of Impressive Statistics

The control center for this grand operation is the Water Supply Operation Center, located in the Hongō district of central Tokyo. Here is where the supply of water and the level of pressure are kept steady on the basis of information about reservoir levels, weather, and expected changes in demand, including exceptional cases like the Japan-Australia soccer broadcast. The center uses state-of-the-art computer systems for this purpose, but it also relies on the time-honored contributions of humans, like the veteran workers who can detect leaks in the system by going around at night, when water demand is low, closing off the pipes in a limited area, and then listening from the surface through special rods, like doctors with stethoscopes.

The monitoring room at the Water Supply Operation Center in Hongō

The monitoring room at the Water Supply Operation Center in Hongō

The numbers prove that Tokyo’s waterworks are the world’s best. The rate of leakage—the percentage of water that is lost on the way from rivers and lakes to users’ taps—is a mere 3.1%. This is much lower than the figures not only for developing countries but also for cities like London and Paris, where the rates are around 20%. And the rate of collection of water charges is above 99.9%. The Tokyo Waterworks are virtually unmatched as a business that provides a constant supply of drinkable water to users’ taps and that makes money in the process. There is nothing “matter of course” about this performance.

Competing with the World’s Water Majors

Human beings cannot live without water. But particularly in developing countries the supply of safe water is severely deficient. Facilities are inadequate, and water is commonly lost not just to leaks but also to theft. Systems for collecting water charges from users are also totally inadequate. Economic development and population growth lead to increased demand for a steady supply of safe water. With this in mind, the Tokyo Metropolitan Government in 2010 launched an Overseas Operations Research Board with the aim of putting Tokyo’s superlative water supply system to work internationally through public-private partnership.

We have known for some time that the Tokyo Waterworks are superb. We also knew that the system had accumulated a store of know-how that could be put to good use in other countries. But previously the efforts to spread this know-how were limited to inviting people from overseas to come and learn about our technology at the waterworks’ Training and Technical Development Center in Tokyo. So the Bureau of Waterworks was undertaking some international cooperation, but there was no idea of doing business internationally.

Making the rounds to check for leaks with listening rods

Making the rounds to check for leaks with listening rods

The water business is a growth field; globally it is expected to amount to an ¥86 trillion market by 2025 and eventually to top ¥100 trillion. But when we woke up to this potential, we found that Japan, with its world-leading technologies and systems in this field, had been left behind at the starting block, while water “majors” like France’s Veolia Water and Suez Environnement and Britain’s Thames Water Utilities had taken dominating positions in the global water business.

These companies have extended their activities to Southeast Asia and other places around the world, investing in large-scale waterworks projects with a view to earning back their money over a 50-year period. The water majors have even established a presence in Japan. Veolia won the contract for the Teganuma treatment plant in the city of Abiko, Chiba Prefecture, for ¥5 billion in competitive bidding, and in April this year it also started to operate a number of purification plants for the city of Matsuyama in Ehime Prefecture. This foreign advance into Japan served as a strong impetus for us as we pushed for a business model aimed at expansion overseas by the Tokyo Waterworks.

Before we could start international operations, however, we needed to clear some hurdles, such as the fact that the law does not allow local government organs to directly contract for the provision of waterworks facilities in other countries. So in order to conduct overseas operations, we decided to use Tokyo Suido Services Co. (suidō is Japanese for “waterworks”). This company, of which the Tokyo Metropolitan Government owns 51% and private-sector firms—Kubota, Kurimoto, and five financial institutions—own the remainder, is involved in maintenance and management of waterworks facilities. We have arranged to have this company and, in some cases, its subsidiaries act as the contracting organs for overseas business. In April 2012 Tokyo Waterworks International Co. was established as a Tokyo Suido subsidiary.

Tokyo’s tap water, the product of advanced water treatment, is also for sale in bottles.

Tokyo’s tap water, the product of advanced water treatment, is also for sale in bottles.

It is difficult, though, for a local government body or a semipublic organ like Tokyo Suido to actively take on risks. I believe the best approach is to have related manufacturers, trading companies, financial institutions, and others be the risk-taking front-line parties and for the local government body to cooperate through the supply of know-how and the like. Since local governments operate the waterworks in Japan, private-sector enterprises have not built up a store of know-how in this field. I think we should share our know-how with the private sector by working together with companies in overseas operations.

What I Saw and Learned in Malaysia

Needless to say, we cannot do business in countries where the idea of paying for water is not present. So our first key task was to determine where and what sorts of projects we might be able to undertake. So far we have dispatched delegations consisting of Tokyo Waterworks employees and Tokyo Suido employees to five countries—Malaysia, Vietnam, Indonesia, India, and the Maldives—to conduct feasibility studies and to publicize the Tokyo Waterworks’ technology and know-how.

Inose and his delegation meet with the deputy minister at Malaysia’s Ministry of Energy, Green Technology, and Water.

Inose and his delegation meet with the deputy minister at Malaysia’s Ministry of Energy, Green Technology, and Water.

I went to Malaysia as the head of the delegation that we sent there in late August 2010. We chose Malaysia as our first destination for a number of reasons: Over the years Japan has been by far the biggest provider of official development assistance to that country, in addition to which Malaysia has a fast-growing economy and a low level of country risk, such as political instability. Also, it has a high level of water leakage and problems with its collection of water charges—meaning that there is great room for improvement through adoption of Tokyo’s system.

Malaysia’s water supply system covers 90% of the country’s population, but as much as 40% of the supply ends up as “non-revenue water” lost to leakage or theft. And the water that comes from the tap is not drinkable. We visited the home of one relatively well-off family to see how they were set for water, and we found that they had an array of purifiers for different purposes. The head of the household noted that buying replacement filters was a significant expense.

Visiting a Malaysian home, the delegation from Japan found an array of water purifiers installed.

Visiting a Malaysian home, the delegation from Japan found an array of water purifiers installed.

What I saw on this trip reconfirmed my belief in the advantage of Japan’s technology, which can offer dramatic improvements in water purity. I believe that in our subsequent discussions we were able to get the Malaysian authorities to recognize the benefits of adopting the Tokyo Waterworks’ system. Malaysia is a federation, and different parties control the national government and the local government of the capital city, which has caused the negotiations to become somewhat tied up, but I am confident that in time we will be able to move ahead.

At this point Vietnam is the country with which we have made the best progress. We are now in the final stages of negotiating an arrangement whereby we would build a water purification plant to supply about 300,000 tons of water a day to the local water utility in Hanoi, where rapid population growth has led to a serious shortage of water. This project involves only the supply of water; we would not have to take on the risk of collecting payment from users. As with other fields, it is appropriate to choose from various types of involvement in the water business.

Rethinking Japan’s “Give-Only” ODA

My visit to Malaysia also left me with another strong impression, namely, the shortsightedness of Japan’s approach to providing official development assistance. Our delegation visited the site of one Japanese ODA undertaking, the Pahang-Selangor Raw Water Transfer Project. It involves digging a tunnel of five meters in diameter for a total distance of 45 kilometers to transfer raw water from the northern part of the country to the capital. The total cost of the project is ¥120 billion, of which ¥82 billion is being funded with a concessional yen loan from Japan.

Members of the delegation visit the site of a water transfer project being built in Malaysia with Japanese ODA.

Members of the delegation visit the site of a water transfer project being built in Malaysia with Japanese ODA.

This is clearly a very meaningful project for Malaysia, but when I heard the details I became angry. Japan’s technological skills are being used to build a dam and dig a tunnel, but that is the end of the story. Why didn’t anybody involved think of including the construction of a purification plant as part of the project? That would create the possibility for a company like Tokyo Suido to maintain and manage the plant. One possibility would be to supply the water wholesale to the local water utility, as planned in Hanoi. If one of the major water companies sees this opening, it may well acquire the rights in question.

The reason this sort of thing happens is that, as I noted earlier, the concept of turning water supply operations into a business is lacking. There is a tremendous difference between simply building the minimum infrastructure and telling the authorities in the target country that it is up to them to use it as they will and an approach that leads to overseas business operations for Japan—while, of course, also bringing great benefits to the target country. It is high time for us to reconsider our handling of ODA, which up to now has tended to be a “give-only” undertaking.

Eliminating Bureaucratic Sectionalism and Working as an “All Japan” Team

Mobile phone handsets consist largely of Japanese-made components, but as final products they are taken as being made in other countries. This is what happens when you are just selling individual parts. Even the much-bruited exports of Japan’s Shinkansen bullet trains are not going all that well because the manufacturers of the railway cars are effectively trying to do business on their own. If the cars were sold as part of a package including the operating system, the offerings would be much more competitive and offer much more added value.

In the case of the water business as well, filtration equipment and other superior “parts” (component technologies) are being exported from Japan to countries around the world, and companies like Veolia and Suez are making profits by selling packages incorporating these components. So the picture is similar to that in other fields.

What we are aiming to do is to compete in the water market as a combined fleet with Tokyo Waterworks as the flagship and private-sector corporations in formation around it. This way we can generate both profits and jobs for Japan. To reiterate what I noted earlier, Japan has waterworks technology and know-how that nobody else can match.

One fact that has become painfully evident to me in the course of our drive to develop overseas water business is that old-fashioned bureaucratic sectionalism continues to act as the biggest impediment to efforts aimed at creating an “All Japan” team for this purpose. People from Tokyo Waterworks had to make the rounds of five separate national government ministries in order to explain what we had in mind. Since waterworks are operated by local governments, they come under the purview of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. Water quality management is under the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs handles overseas moves in general, while the Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry is responsible for overseas operations by business corporations. And the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport, and Tourism oversees infrastructure improvements. Having five separate ministries involved in the water business is surely inordinate.

The Conceptual Deficiency Underlying Japan’s Failures on the Global Stage

Despite all the noise we hear about the importance of globalization, Japan keeps suffering defeats in global markets. Why is this? I believe the underlying cause is a problem at the conceptual level.

In the nineteenth century, when Japan was threatened by Western powers, the Japanese came up with the idea of “Asianism”—promoting the modernization of lagging Asian countries and together standing up against the West. If we had even a scrap of that sort of thinking, we would not see cases like the one I mentioned above in connection with ODA for Malaysia’s water supply infrastructure. It seems to me that we are still stuck with a vague sense of guilt for Japan’s wartime behavior toward other Asian nations, which is resulting in a “give” only approach to our economic cooperation.

This sort of conceptual deficiency was present even in prewar Japan. The most critical fault was the rigidity in human resources development. In the case of the Imperial Japanese Army, for example, a student’s grades at the Army Academy determined whether he could advance to the Army War College, and a student whose grades there were even one point higher than his classmates would garner promotions and eventually become a general. This is what gave us military leaders like Tōjō Hideki and the other “model students” who were unable to act decisively to prevent Japan from heading down a path of national ruin.

In the army’s early days, back in the nineteenth century, there were factions associated with the old feudal domains, and advancement through the ranks depended partly on connections, but there were also fast-track promotions of talented individuals. In a reaction against the blatant cronyism of connections-based promotions, a system of what we might call “Japanese fairness” was adopted, with promotions based strictly on objective criteria like grades. But this blocked the way for the fast-track advancement of especially talented individuals that is essential for organizational vitality. This “fair” system was able to take hold partly because Japan was at peace for an extended period following the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–5. In the preceding decades of turmoil, there was a constant sense that unless promising people could be found and promoted to positions of responsibility, the organization was liable to break down.

Mavericks Change the World

A similar process occurred again after World War II. In the period of postwar confusion, talented bureaucrats scrambled to get Japan back on its feet, and energetic newcomers brashly founded and grew companies like Sony and Honda. But from around the 1970s on, the top ranks in Japan’s organizations again came to be filled with “model students.” These were people who were good at getting top grades in examinations but who, like Tōjō, lacked leadership abilities.

Last year I posted this piece of advice on my Twitter page: “Young people: Don’t aim to match the model student beside you. Be a maverick.” Trying to catch up with the person next to you who gets better grades will not produce original thinking or help you acquire leadership ability. I believe that the people who change the world are the mavericks—people like Koizumi Jun’ichirō (prime minister 2001–6) and Ishihara Shintarō (governor of Tokyo since 1999), two “maverick” leaders with whom I have worked, neither of whom is anything like a model student.

Japanese organizations, with their group mentality, are well suited to performing precise tasks. This is what has made it possible for Tokyo’s Bureau of Waterworks to achieve the low leakage ratio of 3.1% and to adjust the volume and pressure of the water supply from minute to minute. This performance is truly a treasure. But turning it into a business requires maverick thinking. What today’s Japan needs is leaders capable of breaking the hold of established mind-sets so as to generate sales revenues from these treasures.

Japan’s society is not without latent capabilities. The problem is our inability to make optimal use of our numerous treasures. In the wake of the March 2011 disaster, we have been hearing the term national crisis used in reference to Japan for the first time since World War II. It is time for us to find our treasures and start writing new tales of accomplishment. And I intend to do everything possible to assure the success of the Tokyo Waterworks’ overseas move so that it can be included among these tales.

(Originally written in Japanese. Compiled by Minamiyama Takeshi from an interview with Inose Naoki on April 24, 2012. Inteviewer Mamiya Jun is a member of the Nippon.com editorial committee.)

Photos: Tokyo Metropolitan Government. Interview photos by Ōkubo Keizō.Link

Bureau of Waterworks, Tokyo Metropolitan Government.Koizumi Jun'ichirō Economic growth Ishihara Shintarō official development assistance ODA Inose Naoki infrastructure waterworks water business Tokyo Metropolitan Government water public utility