The Challenges for China’s New Leadership

China’s Environmental Picture: A Pastiche of Light and Shadow

Politics- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Not long ago an acquaintance shared with me some photos of China that bear witness to dramatic environmental changes—both positive and negative—that have been sweeping that country in recent years. The pictures, divided into three groups, were taken last summer during a study tour of the areas around Beijing and Datong (Shanxi Province) organized by the Japanese nonprofit group Green Earth Network (GEN), which has been promoting greening projects in and around those northern Chinese cities for the past 20 years. Taken together, the photos illustrate the light and dark sides of China’s evolving environmental policy.

Breathtaking Progress in Wind Power

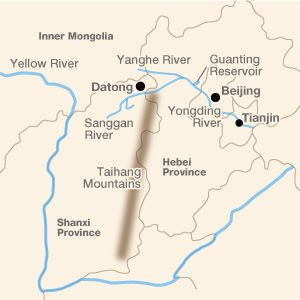

The first group of photos depicts a wind power generation facility that stands near the Guanting Reservoir, which supplies much of Beijing’s water. The reservoir was created for that purpose in 1954 by the construction of a dam on the Yongding River in Hebei Province, near where the Yongding emerges from the confluence of the Sanggan and Yanghe rivers. The Sanggan’s source streams rise from the mountains around Ningwu County, just south of Datong, in Shanxi Province (named for the Taihang Mountains that rise along its eastern border and separate it from the North China Plain). The waters that feed the Yanghe originate in the highlands to the north of Datong in northernmost Shanxi and Inner Mongolia. Thus, northern Shanxi Province—and the Datong Basin in particular—provides most of the water that goes into the Guanting Reservoir. After that, the Yongding continues south through Beijing and on toward Tianjin.

Northern Shanxi is known not only for the waters that help fill the Guanting Reservoir but also for the prefectural-level city of Datong, capital of the Northern Wei dynasty (386–534) and site of the Yungang Grottoes. The city is located in the Datong Basin, through which the Sanggan River flows before cutting through the mountains and into Hebei. The northwesterly winds from the continent sweep through these lowlands and into Beijing, dusting the city with the fine yellow dust called loess. This wind also powers a huge wind farm adjacent to the Guanting Reservoir—the main focus of the first group of photos.

Northern Shanxi is known not only for the waters that help fill the Guanting Reservoir but also for the prefectural-level city of Datong, capital of the Northern Wei dynasty (386–534) and site of the Yungang Grottoes. The city is located in the Datong Basin, through which the Sanggan River flows before cutting through the mountains and into Hebei. The northwesterly winds from the continent sweep through these lowlands and into Beijing, dusting the city with the fine yellow dust called loess. This wind also powers a huge wind farm adjacent to the Guanting Reservoir—the main focus of the first group of photos.

The photos of the Guanting Wind Farm testify to the dramatic growth of wind power in China over the past few years. Construction on the wind power project began in 2006, and by August 2008 the plant was able to produce “green energy” to power the Beijing Olympics. The 33 wind turbines completed during phase 1 of the project have a combined capacity of almost 50 megawatts and were estimated to yield an annual CO2 emission reduction benefit of 100,000 tons.(*1) Since then more turbines have been added, and last May the government announced online that it was accepting bids for phase 12, which is to boost the plant’s total capacity by another 150 megawatts. One key reason the Guanting Wind Farm has been able to proceed so rapidly is that the wind farm is located next to the reservoir, far from human settlements. This all but eliminates the controversy over low-frequency noise pollution, which has plagued Japan’s wind power projects.

The Guanting Wind Farm is just one of the more obvious indications of China’s overall progress in the area of wind power. It is a development that has not gone unremarked by Takami Kunio, secretary-general of the aforementioned nonprofit GEN. In the September 28 issue of his online newsletter Kōdo Kōgen–dayori (Loess Plateau News), he draws attention to the Global Wind Energy Council’s 2010 (year-end) ranking countries by installed wind power capacity, noting that for the first time, China (42.3 gigawatts) had overtaken the United States (40.2 GW). Germany ranks third, with 27.2 GW, while Japan is far down the list with a mere 2.3 GW. Takami also notes that China far surpassed every other country in the installation of new wind power capacity during 2010. That year China added 16.5 GW, accounting for 46% of the global increase in wind capacity (35.8 GW, or a 22.5% annual increase in global capacity) during the period. The United States came in a distant second at 5.12 GW, while Japan ranked eighteenth, with a mere 221 MW of new wind power capacity.(*2)

Looming Water Crisis

While the growing array of wind turbines around the reservoir illustrate the bright side of China’s environmental landscape, one need not look far to see a darker side. In addition to the Guanting Wind Farm, the photos taken in the area show us a reservoir going dry. Thanks to the ever-increasing use of groundwater and river water to irrigate the farms that have been spreading across the Loess Plateau to the west, the water entering the reservoir has dwindled sharply over the years. This situation, combined with pollution from industrial waste and other sources, has made the water in the reservoir unfit for drinking since 1998. That in turn has contributed to the overexploitation of Beijing’s groundwater resources.

Rich groundwater resources have allowed Beijing to function and grow as China’s capital almost continuously for seven centuries, ever since the Yuan dynasty (1279–1368) established its seat there. Prior to the construction of a municipal water system, most residents purchased their drinking water from sellers who were licensed to draw water from local wells and deliver it throughout their designated neighborhoods using carts and buckets hung from carrying poles. According to contracts dating from the Qing dynasty (1644–1912), they also used the pole-and-bucket apparatuses (goudan) to draw the water, suggesting that the wells in use were no deeper than the combined length of the pole and a typical water seller’s arm, or about two meters.

It was not until the 1980s that Beijing’s growing population and other factors combined to produce chronic water shortages. Since then, plummeting reservoir levels and the ensuing excessive groundwater extraction have caused the water table to fall at an accelerating pace. The depth of local wells dropped from about 3 meters in the 1960s to 11.88 meters in 1998. In this century, the water table fell to 15.36 meters in 2000, 20.21 meters in 2005, and 24.90 meters in 2010.(*3) To address Beijing’s water troubles the government has been implementing a colossal program known as the South-North Water Transfer Project to divert water from the Yangtze River to northern China. But even if the project proceeds according to plan, it may not be enough to meet Beijing’s ever-growing demand for water. To get to the root of the problem, China needs to launch a wholesale campaign to replenish water sources in northern Shanxi. But all evidence suggests that things are moving in the opposite direction.

In 2002, I traveled to Shanxi’s Tianzhen County on the northeastern corner of the Loess Plateau, an area under the administration of Datong. Since the second half of the 1990s, the county’s water table had been falling at the rate of a meter a year, and by the time of my visit, it was necessary to drill down some 80 meters for well water. One major factor behind this development is the increased cultivation of profitable vegetables like green peppers, the demand for which has risen along with China’s living standards over the past decade. More and more, local groundwater is being pumped to irrigate greenhouses for such crops.

Groundwater levels have a major impact on river discharge. The Sanggan River, a main tributary of the Yongding, has been mostly dry year-round since the second half of the 1990s. A few puddles remain at the bottom of the riverbed, but the rest is dirt and mud and a salty white film. The water that flows there intermittently, usually after a major downpour, is black with mud and contaminant. This is the water that flows into the Guanting Reservoir.

Dark Side of Local Development

The second group of photos I received was also surprising. These were photos of a tourist attraction recently built outside the famous Buddhist Yungang Grottoes near Datong, which UNESCO has designated a World Heritage site. The Shan Tang Shui Dian, as it is called, is a reconstructed Northern Wei palace, said to have been designed in accordance with description in the Northern Wei geographical work Shui jing zhu (Commentary on the Waterways Classic). It is built over an artificial lake brimming with water.

For many years, Datong’s major industry has been mining, but the current mayor has invested huge sums with the goal of shifting the emphasis from coal to tourism. Since 2008, the city has spent some 800 million yuan (roughly $125 million) to improve scenic views in the area of the Yungang Grottoes—razing homes and displacing thousands of residents in the process. The photos of this pleasant scenery clearly show only one side of this local drive to shift from a mining to a tourist economy.

When I visited the Yungang Grottoes in the spring of 2010, the Shan Tang Shui Dian was still under construction. At that time I was told that the central government was so far withholding approval to fill the pond, out of concern for the water-conservation implications. If these photos are any indication, the cause of local economic development has won out over the central government’s concerns. The structure stands as a vivid symbol of the ongoing conflict between the central government’s goal of sustainable development under Hu Jintao’s policy of hexie shehui (harmonious society) and provincial governments’ determination to build up local economies regardless of the wider environmental impact.

The third group of photos shows a small pond about five meters in diameter, surrounded by trees. The pond is situated in the Nantianmen Natural Botanical Park in the mountains of southern Datong, a project that GEN launched in 1998. Initially the site had nothing but a tiny spring, barely large enough to chill a few bottles of beer. But over a decade and more of loving care, the flow gradually increased until it was able to feed a full-fledged pond. For me, this is a scene with no dark side to it.

Exporting the Satoyama Concept

Reforestation is another area of environmental policy that has yielded dramatic, if mixed, results in China. The percentage of wooded land in the country has been increasing rapidly under a broad-ranging government program to replant trees in areas denuded by logging, grazing, and other activities. Unfortunately, most of the reforestation has been in the form of orderly, single-species stands of fast-growing poplars and pines.

The Chinese typically see little value in naturally reforested land with diverse vegetation reflecting the local ecology. They call such land huang shan, a harsh wilderness. It will take a kind of cultural leap before they begin to see the beauty of mixed trees and plants growing naturally in an area free from human interference. This may be an area where outsiders can play a significant role.

During the course of its environmental activities around Datong, GEN discovered some out-of-the-way spots where the woodland was naturally returning to areas that were formerly stripped bare of trees. It was an example of how denuded land can, if left undisturbed, revert to its former state naturally, without heavy-handed interference by human beings. Inspired by this discovery, the group obtained permission to take over a barren hillside in the Taihang Mountains and turn it into a natural park. The goal was to study the process by which the original flora can return to an area if the land is carefully managed and protected from disruptive human activity.

The group planted thorn bushes along the perimeter to prevent grazing and stationed wardens to prevent any cutting of trees or vegetation. Soon bush clover and other plants were growing along a mountain slope where previously little had flourished besides the poisonous “crowfoot” that sheep and goats refused to eat. Gradually deciduous trees began to spring up as well, aided by avian visitors whose excrement contained the seeds of trees growing nearby. (No doubt birds have also eaten the fruit of trees growing in the park and spread the seeds elsewhere.) As trees proliferated, the ground was able to hold more water, and the tiny spring on the hillside grew larger and larger.

In recent years Japanese environmentalists have focused considerable attention on the concept of satoyama, the mixed woodland typically found on the outskirts traditional Japanese rural communities, which were communally owned and managed by the villagers. The satoyama lay between the village and the okuyama, the deep wilderness that was regarded as home to the local gods and left largely untouched. The idea of preserving these three contiguous zones—human settlement, satoyama, and okuyama—has been revived by a partnership known as the Satoyama Initiative, which has won plaudits from environmental groups worldwide.

Unfortunately, there is no indication that such a tradition ever existed among the Han peoples of northern China, and any bid to instantly transplant the Japanese concept to Chinese soil would almost certainly be doomed to failure.

Exporting cultural values is a slow and difficult process requiring tact and perseverance. It involves living closely with the local people, calling their attention to something they may have overlooked, and encouraging them to discover value in things their traditional culture holds cheap. It takes more time than growing stands of poplars, but meaningful progress in environmental conservation cannot be measured simply by the number of trees planted. It seems to me that one key to global environmentalism lies in this patient process of nurturing a culture of coexistence between human society and the natural environment.

Reference

Ueda Makoto, Taiga shitchō—Chokumen suru kankyō risuku (River Failure: Confronting the Environmental Risk), Iwanami Shoten, 2009.

(Originally written in Japanese in September 2012. Title background photograph courtesy Wonderland-PIXTA. Other photos courtesy GEN member Fujiwara Kunio.)

(*1) ^ Zhongguo nengyuan bao (China Energy News), November 22, 2010.

(*2) ^ “Fūryoku hatsuden” (Wind Power), Kōdo Kōgen–dayori (currently published as a blog), number 567 (in Japanese only).

(*3) ^ Zhongguo huanjing fazhan baogao 2012 (Annual Report on Environment Development of China, 2012), Social Sciences Academic Press, 2012.

China environment Ueda Makoto Makoto Ueda environmentalism dams rivers forests water shortage wells Green Earth Network greening afforestation reforestation