The Challenge of Restoring Japan's Fiscal Integrity

The Convenient Assumptions Behind Japan’s New Fiscal Strategy

Economy- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Postponing the Primary Balance Surplus

The 2018 Basic Policy on Economic and Fiscal Management and Reform, approved by the cabinet on June 15, included a plan to restore the integrity of public finances. This new plan postpones the achievement of a primary balance surplus by general government (central and local), the target for sound public finances, by five years, to fiscal 2025 from fiscal 2020. The plan also aims to steadily reduce the government’s debt-to-GDP ratio.

Reasons given for postponing the primary balance target by five years include (1) tax revenues growing more slowly than initially anticipated due to sluggish economic growth, (2) the effect of supplementary budgets and of delaying the increase of the consumption tax rate, and (3) the change in the way the consumption tax increase, now slated for October 2019, will be allocated to secure stable funds for revolutionizing human-resource development.

What the above suggests is that Abenomics, the economic policies of Prime Minister Abe Shinzō, have not proven effective; that attendant contradictions have caused tax revenues to fall below expectations; and that pork-barrel supplementary budgets on the expenditure side, labeled stimulus measures, have prevented the achievement of the primary balance target. Given the above, what effect will the new plan to restore sound public finances have on economic management?

Assuming High Growth and Continued Easing

First, there is concern about whether the plan to restore sound public finances—which puts off achieving a primary balance surplus for another five years—will be sufficient in managing Japan’s economic and fiscal risks. When considered in relation to the Bank of Japan’s exit policies, engaging in leisurely efforts on the revenue and expenditure sides until 2025 may expose Japan to the risk of a major economic shock.

The new plan assumes that the economy will grow at a rate of 2% in real terms, 3% in nominal terms. These are extremely high figures. Revenues are estimated based on these figures, making it highly likely that government planners are banking on inflated figures. Moreover, the plan assumes that the growth rate will exceed the interest rate until 2025, despite the tendency for long-term interest and economic growth to have similar rates of change in the medium term.

The assumptions above are related to the need to steadily reduce the debt-to-GDP ratio, which was newly added as a fiscal target to the Basic Policies on Economic and Fiscal Management and Reform 2017. If the growth rate of the economy is higher than the interest rate, it could trigger a drop in this new target ratio.

The assumption that growth will outpace interest rates until 2025 will place enormous pressure on the BOJ’s monetary policies. These policies will become subordinate to fiscal policies as they are used to finance fiscal deficits. Major risks will accompany Japan moving in the opposite direction when Europe and the United States are exiting from monetary easing. Also, this convenient assumption will immediately collapse when the BOJ does decide to exit from easing and interest rates are normalized.

No Debate of Higher Taxes Before 2021?

Second, while some effort has been made to curb the growth of expenditures to around ¥500 billion annually in fiscal 2016–18, the new plan includes no similar target for future years. There are reports that this is the outcome of the Kantei (Prime Minister’s Office) not wanting a cap placed on the government budget. But this will remove a standard for drafting each year’s budget, leading to the risk of ballooning expenditures.

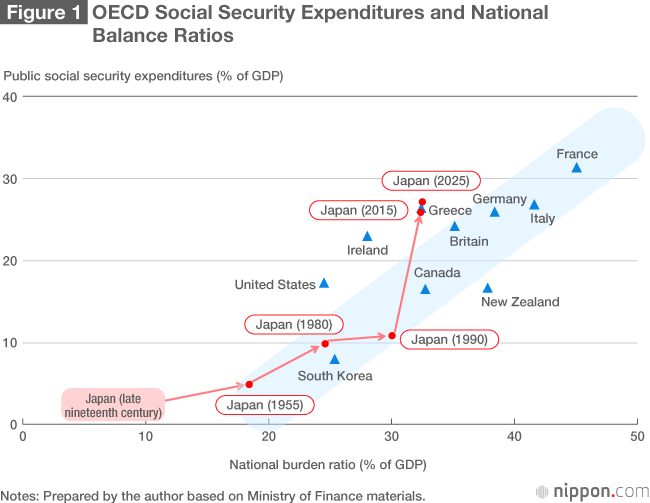

Finally, nothing specific was recorded in the plan regarding the issue of revenues (tax system). Figure 1 illustrates the relationship between social security expenditures and the national burden ratio (the share of taxes and social security contributions in national income) as a proportion of GDP. The chart shows that Japan has fallen greatly out of step with the trend for advanced economies. In other words, seeing how its burden and benefit balance has come to differ from other advanced economies, Japan has missed an opportunity to begin a national conversation on the issue of benefits and burdens.

Meanwhile, the plan is drawing attention for its inclusion of new medium-term indicators and their verification. Indicators will be established for the midway year of fiscal 2021, and progress will be monitored. These indicators are the reduction of the ratio of the primary balance deficit to GDP to half of the figure for fiscal 2017 (about 1.5%), a debt to GDP ratio between 180% and 185% (the ratio is estimated to be around 189% in fiscal 2017), and a fiscal deficit to GDP ratio of less than 3%. When financial resources fall short despite efforts to reduce expenditures and despite the economy’s growth, there is no alternative but to raise taxes. This requires an honest debate. The new medium-term indicators, however, can be viewed as postponing this debate until the medium-term verification scheduled for fiscal 2021.

As the above discussion should make clear, the targets that have been established for restoring sound public finances are less than strict. They risk the sustainability of social security and risk lower government bond prices (higher interest rates). Is it reasonable to think that they can provide citizens with confidence in their future lives and gain the acceptance of markets?

Smoothing the Way to a Higher Consumption Tax

The 2018 Basic Policy specifies raising the consumption tax to 10% in October 2019. It also includes measures to level out changes in demand and tax and budget measures to support the purchases of automobiles, housing, and other durable goods.

In addition, it specifies measures that will control fluctuations in demand before and after the increase of the consumption tax rate by having businesses freely set prices in response to demand according to their judgment. What will this mean in specific terms?

The increase of the consumption tax in April 2014 was accompanied by a surge in demand for durable goods beforehand and a falloff afterward, which had a huge negative impact on business management. This has become a reason for opposition to further rate increases, mainly from reflationists.

In European nations like Germany and Britain, economic fluctuations have been extremely small before and after consumption tax hikes. What accounts for this difference between Japan and Europe? This reason should be identified to make appropriate changes in Japan.

Consumption Tax as a Cost in Price Formation: The European View

The consumption tax is an indirect tax paid by final consumers through higher prices. While businesses are liable for the tax, final consumers are the ones who pay it. Whether this cost can actually be transferred to consumers will differ depending on such factors as changing economic circumstances (whether demand is strong), the power relationship between businesses, price leadership, and the price competitiveness of products.

What explains the small fluctuations observed for the economies of Germany, Britain, and other European nations when the consumption tax is raised? The decisive factor is a difference in thinking with Japan regarding the tax and prices. European businesses have a long history of viewing consumption tax in the same way as labor cost or cost price, itemsw whose levels change daily. It is simply one of the costs factored into the formation of prices. If the consumption tax is about to be raised, businesses will set prices while monitoring the trend for demand and bearing in mind the tax increase schedule. Since a surge in demand can be expected before the tax increase, many businesses will raise selling prices to book profits.

In Japan, however, businesses are regulated and directed excessively by the government and the Fair Trade Commission, in part because of the high levels of consumer and media interest in price gouging and excessive price transfers accompanying the tax increase. Price hikes are regulated prior to a consumption tax hike, and sales offsetting the higher tax afterward are also forbidden. As a result, businesses change price tags all at once the day before the hike takes effect.

Such measures are not seen in Europe. The conformance in Japan to excessive regulations robbing businesses of the freedom to set prices is producing a surge in demand before a tax increase and a falloff in demand afterward.

More Freedom Needed for Retailers

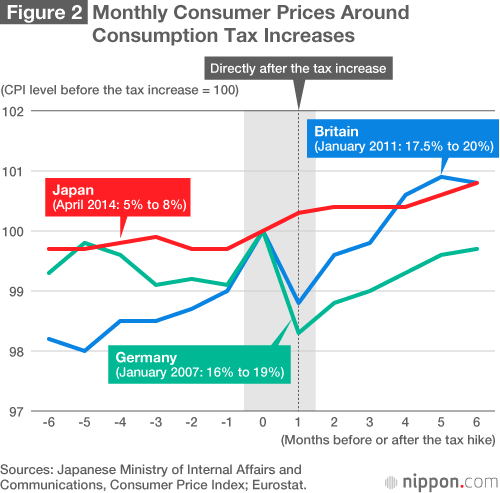

Figure 2 illustrates price trends before and after the consumption tax hike of April 2014. The perceived lower prices before a hike amplify the surge in demand, while the increase of prices paid by customers afterward amplifies the falloff. As discussed above, the pattern seen in Europe is for businesses to raise prices in advance of a tax hike to book profits when demand is strong. Then, as demand weakens after the tax hike, businesses raise prices slowly. Thus, increasing retailers’ freedom to set prices is a measure needed to level out demand.

It bears mentioning that businesses’ response to consumption tax increases reveals a misunderstanding. The consumption tax to be paid is calculated by subtracting purchases × consumption tax rate from sales × consumption tax rate. This becomes (sales – purchases) × consumption tax rate, meaning that the amount of the consumption tax is calculated with total gross profit (value added). The consumption tax is transferred onto total sales and not onto individual products. Businesses are free to keep prices the same for products intended to draw customers and to set prices all the higher for other products.

The awareness of the mass media and consumers will also need to change. They should rethink the meaning of excessive price transfers and price gouging and make judgments based on accurate knowledge.

Finally, businesses will need to refrain from sales strategies that aim to amplify surges in demand ahead of a tax hike, since they are certain to be revisited with falloffs afterward.

(Originally published in Japanese on June 29, 2018. Banner photo: Prime Minister Abe Shinzō, third from right, speaking at a joint meeting of the Council on Economic and Fiscal Policy and the Council on Investments for the Future held on June 15, 2018, at the Kantei. © Jiji.)