President Xi’s Second Term: Prospects for Japan-China Relations

Chinese Technological Innovation Transforming Sino-Japanese Economic Relations

Economy- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

China’s New Normal

The Chinese economy, now the second largest in the world, is approaching a major turning point. The official view in Beijing is that since 2014 the economy has entered a “new normal condition” of steady growth. The government plans to continue with reforms prioritizing market mechanisms and has announced a strategy aimed at encouraging a shift away from the relentless investment-dependent growth that has dominated previous decades.

One aspect of this switch drawing widespread attention is the growing boom in Chinese technological innovation. In 2015, the central government launched a policy calling for innovation and entrepreneurship by the masses as a new driver of economic growth, and support for startups and innovation is proceeding at pace on the regional government level as well. The same year also saw the State Council publish Made in China 2025 outlining the country’s ten-year strategy for bolstering its industrial prowess through innovation that brings together IT and manufacturing.

At the heart of this new drive to innovation is Shenzhen in Guangdong Province. Established as China’s first special economic zone in the 1980s as the country adopted a policy of greater openness to the outside world, Shenzhen in its early years as a center of the new economy grew rapidly as a hub for labor-intensive industries. Later, it became home to what are called special markets (mixed-use commercial buildings packed with wholesalers and manufacturers) that supply a diverse range of electronic components. To this day the city remains a major center of the electronics industry.

One of the biggest characteristics of electronics in Shenzhen is the way in which companies with very different views toward intellectual property rights—something closely linked to innovation—exist side by side.

One company that is particularly protective of intellectual property rights is Huawei Technologies, the business-to-business giant that accounts for around 60% of sales of telecommunications-focused computers and telecommunications devices. Huawei is an innovation leader, with some 80,000 employees engaged in research and development, and for the past decade has consistently placed among the top five companies worldwide for the number of patent applications filed. With their technical expertise and massive R&D investment, companies like Huawei and ZTE have aroused suspicion from the US government and industry, with ZTE being singled out for strict sanctions.

Another interesting aspect of the Shenzhen innovation boom is the presence of companies ready to fund innovative start-ups. One of the central players in this so-called makers’ movement is Seeed Studio, a firm that produces small-scale orders of customized PC boards and other electronic components on demand. The company goes to extraordinary lengths to ensure that all the technological data behind its products are freely available to the public. This reflects the progressive view that companies should not protect technology with patents, but should promote innovation by making it available for anyone to use and improve on.

In the electronics stores of Huaqiangbei in the north of the city, the situation is quite different. Here, customers pick through piles of cheap smartphones and other knock-offs. The notion of intellectual property rights means nothing here.

A rough way of summarizing the situation might be to say that three totally different attitudes to intellectual property coexist in the Shenzhen electronics industry. First is the “premodern” position of manufacturers that sell cheap fakes and ignore intellectual property rights altogether. Next is the “modern” stance of companies like Huawei who rigorously use patents to protect their intellectual property. Finally, there is the “postmodern” open-source approach of companies like Seeed. It is fair to say that this diversity in approaches, which could never have arisen through top-down planning, is one of the major strengths driving Shenzhen’s success.

Changing Economic Relations Between Japan and China

The makers’ movement is playing a major part in driving the Chinese innovation boom and is transforming Shenzhen into one of the most global cities in all of Asia. In recent years, many Japanese have started closely following these developments and begun to get involved. There have even been regular calls to venture companies to take part in observation sessions online.

One of the guiding lights for Japan in the movement is Takasu Masakazu of electronic tool and component maker Switch Science. I was inspired by his book on the emerging ecosystem of the makers’ economy and took part in a meeting led by Takasu. I was impressed by the highly diverse nature of the audience, which ran the spectrum from engineers and journalists to former jockeys and television celebrities.

What I want to highlight here is that the new group of Japanese getting involved in the movement will play a central role in developing the economic relationship between Japan and China going forward. This new generation is characterized by distinct patterns of behavior and ways of thinking that deviate from past norms.

Their engagement with China does not stem from a desire to improve Sino-Japanese relations or their companies’ bottom lines. What draws them to China is an understanding that Shenzhen specifically and China more generally are where exciting new developments are taking place in the fields of industry and innovation. This new relationship between tech geeks from the two countries is at heart of a new type of Japan-China human network centered on Shenzhen.

It is worth looking briefly at the history of economic relations between Japan and China. During the honeymoon period following the normalization of diplomatic relations in 1972, economic cooperation between the two countries was dominated by heavy industries like steel, oil, and electric power, as symbolized by Baoshan Iron and Steel headquartered in Shanghai. Likewise, the main conduits and fixers in the relationship between the countries tended to be people with connections to major companies in these same industries.

By the second half of the 1980s, though, the dialogue and negotiation channels that Japan and China had built during this early period started to fail. As China shifted from an economic development framework that prioritized heavy industry to an export-driven model leveraging its comparative advantages, the fulcrum of its economic relationship with Japan shifted toward direct investment in manufacturing. However, the communication channels between the two countries continued to be dominated by people in heavy industry and petrochemicals, who were often unable to adjust to the challenges then emerging in Sino-Japanese relations.

As direct investment in China by Japanese companies increased, Japanese popular sentiment toward China worsened. In 1995, the Cabinet Office’s annual survey on public views found for the first time that people who felt a sense of closeness to China were outnumber by those who said they felt no such closeness. This negative trend has continued ever since. At the same time, the increasing diversity of economic exchange between the two countries has made it difficult for influential private-sector groups like Keidanren and the Japan-China Economic Association to drive the direction of economic relations.

In 2005 when massive anti-Japanese demonstrations took place in China during Prime Minister Koizumi Jun’ichirō’s time in office, the Japan Association of Corporate Executives and other business groups tried by various means to improve relations, but were unable to dispel mutual feelings of distrust. A new pattern characterizing the relationship in conflicting terms of frosty political relations and burgeoning economic ties.

It was around the beginning of the current decade, following the shift in growth patterns that I outlined at the beginning of this article, that the Chinese government decided to move away from labor-intensive industries to knowledge-intensive, high-tech industries with higher added value. This shift has led to a number of difficulties between local government and workers.

Many Japanese companies have struggled to adjust to these new circumstances. In the years to come, creating business opportunities in China will depend on people who are able to acknowledge talent regardless of nationality, and who can compete and cooperate without being trapped by dominant ideas and conventional ways of thinking. In Shenzhen at least, a space is being born where it no longer makes sense to speak about business in China from the past nation-based perspective of Sino-Japanese relations.

The Relationship Between Innovation and China’s Authoritarian Government

If we wish to understand the innovation taking place in China today, it is vital for those of us living in Japan to pay attention to the relationship between private companies and China’s authoritarian regime. In the past, mainstream political thought tended to assume that sustainable innovation based on free ideas would be impossible under an authoritarian system that limited freedom of speech.

But behind the façade of certain rules fixed by the authorities, the political and economic system in China today not only allows private companies a great degree of freedom to pursue their activities, but also deliberately uses the diversity this promotes to maintain the system.

It may be that the recent innovation boom, which has taken place under a system that lacks strong protection for intellectual property rights, is in some sense the result of collusion among an authoritarian government, a non-democratic society, and an untrammeled private sector economy subject to relatively lax oversight. And this suggests the possibility that the Chinese government in the future will be less inclined than ever to listen to the blandishments of the West, warning that sustainable economic development will be impossible unless China becomes more democratic.

How then should we in Japan balance the benefits to be gained from our economic relationship with China and the Chinese people, including the private sector companies that are the drivers of innovation, with the obligation to protect universal values like human rights and democracy? As a new generation takes charge of the economic relationship between Japan and China, largely unshackled by nationalistic points of view, it is vital for us to look unflinchingly at the facts and think carefully about this difficult dilemma.

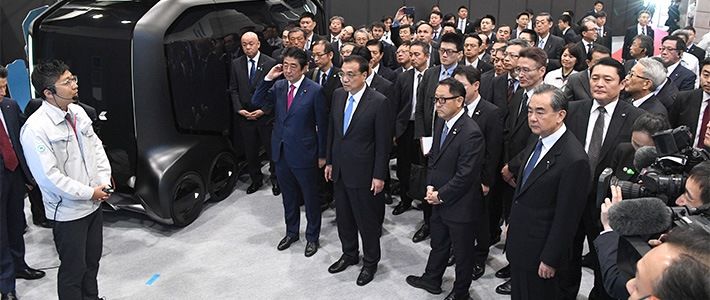

(Originally published in Japanese on May 21, 2018. Banner photo: Front row from right to left, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi, Toyota President Toyoda Akio, Chinese Premier Li Keqiang, and Japanese Prime Minister Abe Shinzō during a visit to a Toyota factory in Tomakomai, Hokkaido, on May 11, 2018. © Jiji.)