Can Japan-Korea Ties Be Mended?

Toward Youth-Led Japan-Korea Exchanges

Politics Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Local Government Exchanges Feel the Chill

These days it is common to preface any remarks about Japan-Korea ties by saying that although relations between the two countries are at their nadir now, this is precisely the time to encourage exchanges. But this is not the first time that relations between Japan and South Korea have been rocky. In 2005 relations worsened over territorial issues like the dispute over Takeshima/Dokdo, how history of the relations between the two countries is presented in Japanese school textbooks, and so forth. As a matter of fact, 2005 had been designated the Year of Korea-Japan Friendship to commemorate the fortieth anniversary of normalization of diplomatic relations, and over 700 related events had been planned in the two countries. Even so, the Korean parliament’s culture and tourism committee adopted a resolution urging that all planned events be reconsidered; some were eventually postponed or cancelled outright. It is ironic that feelings between the two countries in that year ultimately turned out to be the most acrimonious since they resumed diplomatic relations.

Today, issues like compensation to former wartime laborers from the Korean Peninsula and Japan’s removal of Korea from its “white list” of export destinations exempt from the need for permits for shipments of certain materials used in high-tech manufacturing have once again brought relations between the two countries to a low point. While few grassroots level friendship events have been called off so far, this time the chill in relations is having a major impact on exchanges at the local government level. As far as I know, nearly 30 cities and towns in Korea have almost one-sidedly pulled out of sister city or friendship city events, leaving their Japanese counterparts scrambling to deal with this sudden turn of events.

The cancellations were touched off by the Korean city of Busan announcing in July 2019 that it would end support for administrative- and citizen-level exchanges with Japanese sister cities in order to align its position with that of the government. Sensing that this was a move anticipating the wishes of the Korean government, Busan citizens rebelled. They successfully petitioned the city’s mayor to reverse his decision to cancel the long-standing tradition of the city’s participation in an annual re-creation of the visit to Japan of Korean emissaries. This event takes place on the Japanese island of Tsushima, located midway between Busan and Fukuoka. Emotions concerning this particular event were especially strong since it was just two years earlier, in 2017, that Japanese and Koreans had worked together to register the history of the diplomatic missions dispatched by Korea to Japan for nearly 600 years, beginning in the late fourteenth century, in the UNESCO Memory of the World Program.

A re-creation of the arrival of a Korean diplomatic mission: Shimonoseki, Yamaguchi Prefecture, August 24, 2019. Nearly 160 Shimonoseki and Busan citizens took part in the procession through Shimonoseki’s main street. (© Jiji)

Social Media Fuels Consumer Boycotts

We hear that the ill-will between Japan and Korea is being fomented by mass media in the two countries, with biased reporting from some media then being spread via online news sites and social media. Reporting in Korean in leading Korean news sources like the Chosun Ilbo, the Dong-A Ilbo, the JoongAng Ilbo, the Hankyoreh, and the Yonhap News Agency is translated into Japanese and uploaded to their websites. These news stories, originally directed at Korean readers in Korea, gain increased exposure as they are picked up by the main search engines, which can generate negative feelings toward Korea among Japanese and further fan the flames of animosity.

Among Japanese news outlets, none except for Kyodo News distribute news items in Korean. As a result, most of the news that Korean readers access has been interpreted by Korean writers offering coverage of Japanese topics in their own language. While some Japan-related news may tend to pique interest in or curiosity about the country, other stories are inaccurate or lack impartiality.

And nor is the mainstream press the only contributor to poor relations between Japan and Korea. One major difference between 2005 and today is the presence of social media. Social media permits interactive communication, and while it is an influential news source, it also intensifies pressure to conform. Korea’s “No Japan” campaign, which calls for boycotting Japanese goods and travel to Japan, has been fanned in large part by social media.

Koreans in their teens and twenties make up almost half of all Korean tourist travel to Japan. When they are asked why they sympathize with or participate in the “No Japan” campaign, they say they are doing so to send a strong message to the Japanese government or as a way of compensating for not having been able to take part in the resistance to Japan’s colonial rule of Korea between 1910 and 1945, virtue-signaling that they are patriots. Through their participation in or support for the movement, they are also expressing their disapproval of the Japanese government, whose removal of South Korea from the “white list” could impact the high-tech sector and worsen the country’s already high unemployment.

Meanwhile, some young people admit that they take part in the “No Japan” campaign for more passive reasons. They do not want to be forced to support the movement or coerce anyone else to participate but they feel forced to go along because they want to avoid criticism. Others opt out entirely, saying “If I buy Japanese goods in a store, I worry about others customers’ disapproving glances, but if I do so online, nobody will ever know,” or “uploading photos to Instagram is part of the fun of travel, but I kept quiet about my trip to Japan and didn’t post to social media because I didn’t want to get any flak.”

Still others complain that “This enforced conformity makes me feel like I have no freedom and that I’m living in a socialist state. If I want to buy a certain product, I will go ahead and get it.” Slightly older people say “Japan is ideal for visiting with my parents, so it’s too bad that there’s so much disapproval of traveling there now. Southeast Asia is farther away and the food doesn’t agree with us. I really hope that relations between our two countries will warm up soon.”

Even so, people need to be cautious about commenting like that on social media to avoid potential bashing. If they feel they are a minority on social media, their fear of being isolated forces them to stay silent. Not everyone necessarily shares the same opinion, but the “spiral of silence” that exists on social media may be a factor contributing to the deadlock in relations right now.

Closer People-to-People Ties

Although Japan-Korea relations today are described as “the worst ever,” many bilateral events have been cancelled, and Japanese goods are being boycotted by Korean consumers, that is only part of the story. The Japan-Korea Exchange Festival, which started in 2005, took place without incident this year in August in Seoul and in September in Tokyo. Although attendance in Seoul was sparser than in previous years, the event in Tokyo attracted nearly 80,000 people, the second-highest figure in the event’s history. There have been other people-to-people exchanges since normalization of relations in 1965 too.

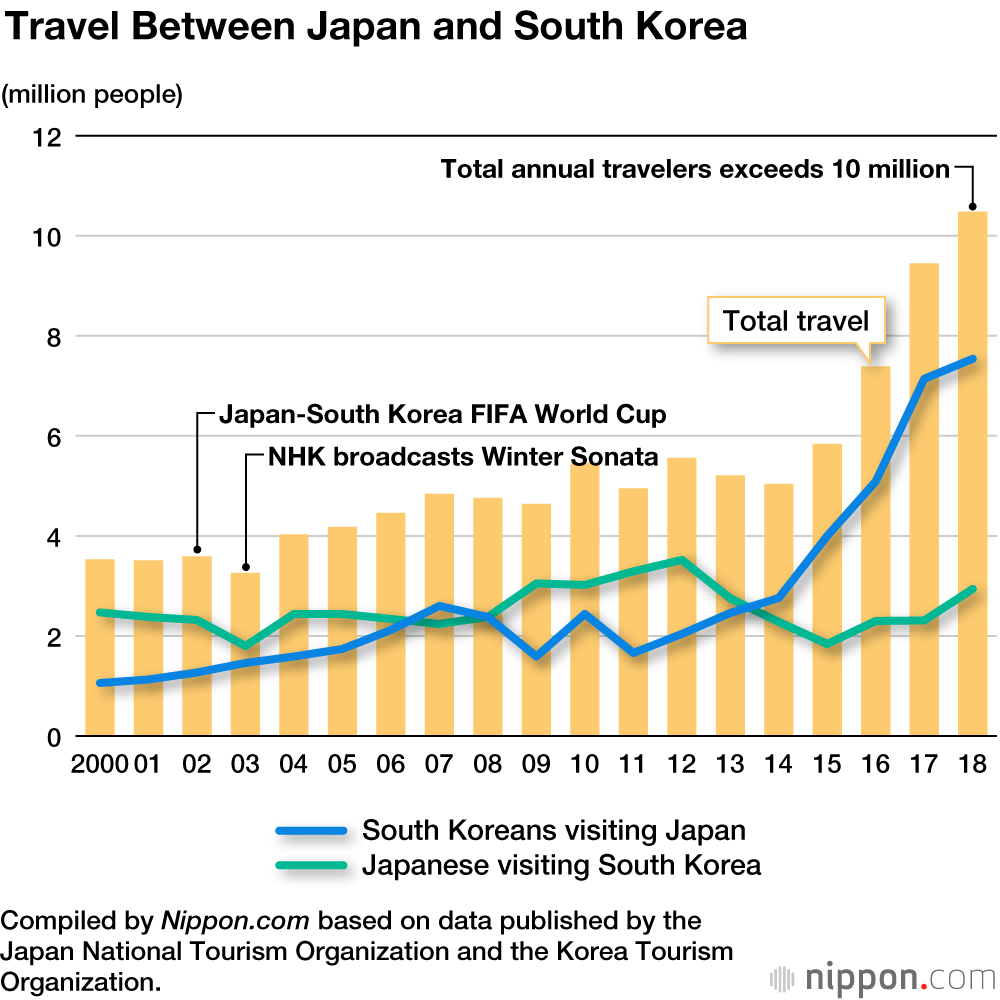

In 2009, when the number of Japanese visiting Korea topped 3 million, women accounted for 50% of the visitors for the first time. Despite the recent dramatic drop in the number of Korean tourists to Japan, more Japanese, mainly women in their teens and twenties, are visiting Korea. In March 2019, 375,000 Japanese traveled to Korea, the highest monthly figure ever. Korea was also the most popular foreign destination among Japanese in the first half of 2019.

Meanwhile, one in seven Koreans—7,530,000 people—visited Japan in 2018. A Japan-Korea opinion survey by the think tank Genron NPO found that as more Koreans visit Japan, more of the Korean public, 31.7% in 2017, have a positive image of Japan.

More Japanese and Korean young people are studying each other’s language too. Today, 350,000 Korean high school students study Japanese. Although at one time more young Koreans chose to study Chinese, nowadays many are learning Japanese, motivated by a desire to get a job in Japan one day.

And in Japan, more teens are studying Korean. Three hundred high schools throughout the country offer Korean language instruction to over 10,000 students. So far, a total of 420,000 people have taken the Hangul Proficiency Test since it was first offered in 1993, and at the 2018 test session one in three test takers was a teen. Nearly 200 Japanese high schools have established sister school ties with Korean counterparts or have regular exchange activities. For example, Hibiya High School, one of Tokyo’s premier secondary institutions, has a short-term exchange student program with a Korean high school because according to the school’s principal, “it’s important for young people to be able to understand each other.”

As of 2018, there were around 17,000 Korean foreign students in Japan, while about 3,800 Japanese go to Korea to study every year. Thanks to exchanges of these kinds on the private citizen level, closer and broader relations are developing between the two countries.

A Role for Politics

Japanese students who have spent time in Korea invariably remark that “Based on what I had heard on the news in Japan, I thought everybody in Korea hated Japanese, but when I got there I found that wasn’t the case at all” or “I was surprised at how many Koreans said they liked Japanese people. That’s not the impression I got from the news on TV.” After actually talking and interacting with Koreans, those young Japanese have begun to think that the two countries’ news media may not necessarily be presenting impartial information. Korean students in Japan feel the same way.

No matter how rocky relations between the two countries may be, it’s important to continue encouraging exchanges between their young people. Every opinion survey on Japan-Korea relations shows that the younger respondents are, the more positive is their impression of the other country. Anything that would damage the positive, forward-looking feelings that the two countries’ youth have toward each other would be a major loss to both countries.

But impressions alone aren’t enough. More should be done to teach young people about differences in the social structures of the two countries and the postwar history of Japan-Korea relations. The younger generation will surely be increasingly influential in the future, so it is up to political leaders to nurture feelings of mutual understanding and respect among the youth of the two countries. It is regrettable that some politicians are calling for cutting back on allocating funds for fostering Japan-Korean youth exchanges on the pretext that no short-term results can be expected from such activities.

One recent trend in student international exchange programs is the gender imbalance in participant makeup: around 80% of participants in Japan-Korea exchange programs are young women. To ensure that Japan has a stable presence in the international community in the future, it is essential for the government to take policy initiatives to encourage young men to show more interest in the outside world.

In Europe, where France and Germany had gone to war against each other numerous times, 8 million French and German young people have exchanged visits to learn more about each other in the more than half a century since the Elysée Treaty of 1963 encouraged such interaction. In Japan, private foundations like the Japan-Korea Cultural Foundation have promoted youth exchanges with Korea, but over 35 years only about 40,000 people have participated.

The results of international exchanges are not all immediately apparent, but it’s important to continue sowing the seeds to nurture mutual understanding. Unless the fire is fed, the light of hope will go out. No one wants to see a future where young Japanese and Koreans feel animosity toward each other.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Japanese and Korean youths performing on percussion instruments at the Japan-Korea Exchange Festival on September 28, 2019. © Jiji.)