The Persistence of Authoritarian Regimes and Asia’s Long Road to Democracy

Malaysia: Authoritarian Persistence and Reform Opportunities

Politics- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

In the 2010s, Southeast Asia experienced forms of “democratic backsliding” and “autocratization.” A coup d’état in Thailand and curtailment of civil and political liberties by Joko Widodo and Rodrigo Duterte, elected presidents in Indonesia and the Philippines respectively, cast a shadow over the region.

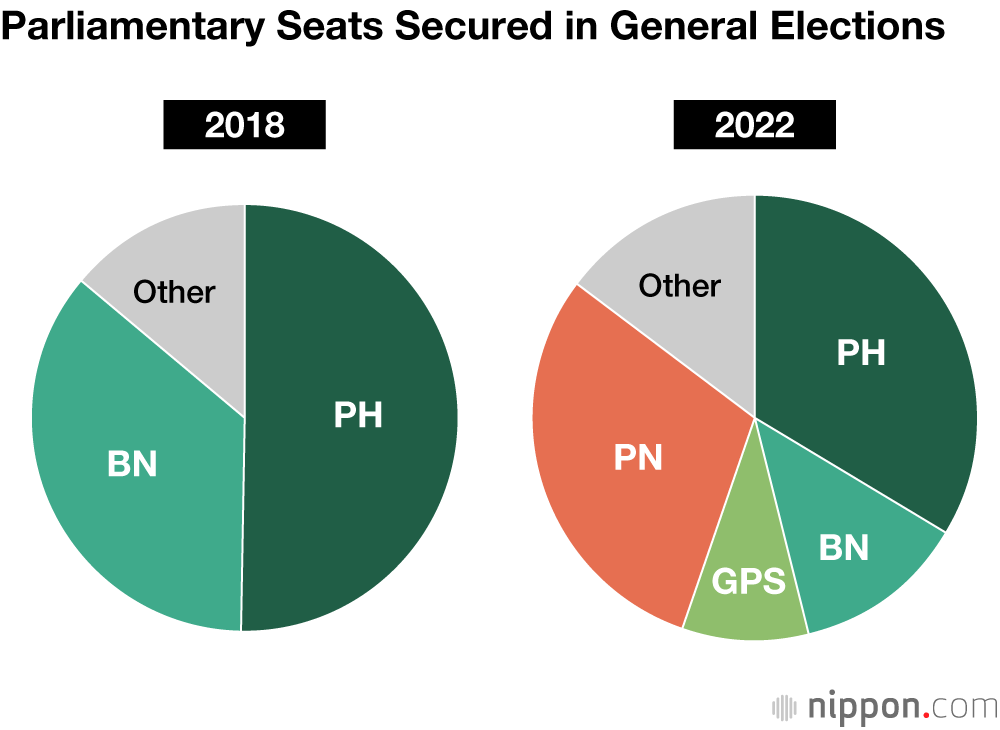

The victory of Pakatan Harapan in May 2018, however, was the one democratic bright spot for the region. Led by former long-serving Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad, PH, or the Alliance of Hope, secured a majority of 121 of the 222 seats in Malaysia’s 2018 lower house parliamentary elections. This coalition of opposition parties displaced the Barisan Nasional (National Front) ruling alliance, ending Malaysia’s dominant party system that had been in place since its independence.

However, in February 2020, the PH administration collapsed. Malay lawmakers who defected from the PH met with opposition MPs from the BN and Parti Islam Se-Malaysia (PAS) at the Sheraton Hotel in Petaling Jaya to discuss how to bring down the Mahathir government. Following what came to be known as the “Sheraton Move,” Muhyiddin Yassin, leader of the Parti Peribumi Bersatu Malaysia, was sworn in as Malaysia’s new prime minister, while PPBM and PAS formed a coalition with Perikatan Nasional and allied with the BN.

Malaysia’s Major Political Alliances and Constituent Parties (as of July 2023)

| Governing Alliances | PH (Alliance of Hope) | Democratic Action Party, People’s Justice Party (PKR, led by Prime Minister Anwar), National Trust Party (Amanah), etc. |

|---|---|---|

| BN (National Front) | United Malays National Organisation, Malaysian Chinese Association, Malaysian Indian Congress, etc. | |

| GPS (Sarawak Parties Alliance) | United Bumiputera Heritage Party (PBB), Sarawak Peoples’ Party (PRS), Sarawak United Peoples’ Party, etc. | |

| Opposition Alliance | PN (National League) | Malaysian Islamic Party (PAS), Malaysian United Indigenous Party (Bersatu), etc. |

Muhyiddin administration lost power as a result of the general election in November 2022. Due to the split between the PN and BN, the election was fought by three forces, namely PH, PN and BN, none of which won a majority of the lower house. The PH, now led by Anwar Ibrahim, won the largest number of seats at 81. However, the PH had to form a coalition with other forces such as the BN (30 seats) and the Gabungan Parti Sarawak (Sarawak Parties Alliance, 23 seats) to form a government.

PH won two general elections in a row by advocating political change. Have the two PH administrations succeeded in reforming the authoritarian political institutions in Malaysia? Or is the legacy and shadow of the BN—now back in government—still alive?

Authoritarian Regime Under the BN

The National Front, or BN, was in power for 45 years up until 2018. While regular elections were held and opposition parties participated and won seats, electoral manipulation was rampant, including malapportionment and gerrymandering. In such exercises, votes of Malays and other bumiputras, or “indigenous” groups, who had historically shown higher support for the ruling alliance, were weighted higher.

In addition, BN also made use of laws that curtail individual freedom, such as the Sedition Act and Societies Act, to silence opposition. The opposition’s ability to seek remedy for their rights was also limited as BN intervened in the appointment of judges and eroded judicial independence. BN was able to use its political and judicial advantages in the face of allegations of corruption surrounding mega infrastructure projects and privatization projects. These institutions and practices were largely perfected during the Mahathir administration (1981–2003).

The 2018 General Election

In the lead-up to the 2018 election, Najib Razak, who became the last prime minister (2009–18) of the decades-long BN rule, mobilized the entire authoritarian apparatus to limit the damage of a scandal surrounding the state investment company 1Malaysia Development Corporation (1MDB). As the worst corruption incident in Malaysian history, the 1MDB scandal angered many voters who were struggling with rising cost of living partly due to subsidy cuts and the introduction of the goods and services tax.

When the members of UMNO, the largest party in the BN alliance, began to criticize the prime minister, Najib arrested his critics one after another using the Sedition Act and the 2012 Security Offences (Special Measures) Act among others. Najib also neutralized major figures in the UMNO, including by removing Deputy Prime Minister Muhyiddin from power and stripping Mahathir of party membership.

Mahathir’s departure from the UMNO led to the former prime minister forming Bersatu and joining Anwar’s PH alliance. PH’s policy platform included addressing the living costs crisis by abolishing the goods and services tax and raising minimum wages, lowering the voting age to 18, and thorough investigation of the 1MDB scandal. Under slogans and catchwords such as “new Malaysia,” rule of law, and the restoration of national pride, the PH alliance was able to win the majority of the lower house and oust the BN from power for the first time in Malaysia’s history.

Reforms During the Mahathir Administration

The Mahathir administration wasted little time addressing the 1MDB scandal, having Najib’s private residence raided a week after the election. Najib and other corrupt officials were then prosecuted. In addition, the government ambitiously initiated reforms and shook up the Attorney General’s office, the Anti-Corruption Bureau, and the Electoral Commission, while lowering the voting age.

However, these reforms did not go as far as liberal voters had hoped for. legislation including the Sedition Law were kept in place, and the 2012 Peaceful Assembly Act was only slightly amended. The promised ratification of the UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination also did not materialize. Malays from both the ruling and opposition parties opposed ratification due to worries about the Convention undermining the “special status” of Malays and other bumiputra. Mahathir’s appointment of non-Malays to posts traditionally held by Malays, such as the attorney general and minister of finance, also aroused antipathy among Malays.

Malays opposition forces such as UMNO labeled PH an anti-Malay government, and stimulated negative sentiment through rallies and SNS. As the PH lost ethnic Malay support, its members began to lose by-elections. The conflict between Mahathir and Anwar over the prime minister’s post, combined with the leadership struggle within the largest party in the ruling coalition, the People’s Justice Party (PKR), headed by Anwar, amplified discord within the PH, culminating in the “Sheraton Move” that brought down the government.

The 2022 General Election and the Anwar Administration

With the PH’s victory in the general election in November 2022, Anwar became the prime minister. Given Anwar’s repeated experience of political persecution since 1998, there was a heightened expectation for political liberalization. Initial successes include Anwar presiding over the abolition of the mandatory death penalty for 11 crimes.

By and large, however, Anwar’s administration has been cautious about rapidly reforming the political system. Ministers still refuse to amend the Sedition Law or the Najib-era Security Offences (Special Measures) Act. There is also continued support for monitoring online media and even proposals to amend the Communication and Multimedia Act of 1998 to enable the prosecution of slander and provocations that touch upon sensitive ethnic and religious matters, as well as the sultans.

Furthermore, in March 2023, former Prime Minister Muhyiddin was arrested and indicted on suspicion that some of the funds spent during the PN regime to support construction companies were diverted to the Bersatu party. When his supporters gathered to demonstrate against the government’s move as political persecution, Prime Minister Anwar himself made use of the Peaceful Assembly Law to repress dissent. Stalled reform of the political system has provoked criticism from human rights groups and lawyers, who have become increasingly disappointed.

Prime Minister Anwar’s priority is to prevent a repeat of the Sheraton Move. The opposition PN, with 74 seats, threatens Anwar with the specter of another government collapse, citing discontent among the parties from the coalition government. Furthermore, Anwar is wary about UMNO president Ahmad Zahid Hamidi and other lawmakers in the BN who remain sympathetic to Najib. They retain the option of withdrawing their support for Anwar depending on the outcome of their own corruption trial and the royal pardon of Najib, who was sentenced to 12 years in prison.

The modification or repeal of repressive laws in such a politically unstable situation would also mean Anwar giving up the means to defang his political opponents. In addition, political reforms may offend the UMNO, which is not ideologically interested in political liberalization, particularly if it involves the special status of the bumiputra. Given these circumstances, the prospects for fundamental reform of the authoritarian apparatus are not necessarily bright, even in the Anwar administration.

Reform Dialectics

Slow or stalled reform is nothing new in Malaysia. In the past, attempts at political reform have usually failed to bear fruit: Mahathir’s successor, Abdullah Badawi (2003–9), touted political liberalization to win the support of young and urban voters. His gesture encouraged Malaysians to air their voices on issues such as affirmative action for Malays and bumiputra and political reform. However, Abdullah had to pull back from the liberalization agenda when UMNO members radicalized over affirmative action. His administration also used police force to suppress the social movements demanding electoral reforms and protection of the rights of ethnic minorities.

In a backlash against this repression, BN lost a significant number of seats in the 2008 elections. Najib replaced Abdullah as the prime minister and advocated reforms, declaring his intention to repeal or amend repressive laws and introduce affirmative action based on income levels rather than ethnicity. However, both were met with opposition from UMNO and other Malay groups, and his reforms were severely watered down.

Stalled reforms by the two BN administrations prompted non-Malay voters to support the PH. However, elections in Malaysia cannot be won without the support of ethnic Malays and other bumiputra who make up nearly 70% of the population. They are also predominantly voters from rural constituencies that are smaller in size, meaning their votes carry more weight. Moreover, as indicated by the performance at the last election of the Islamic PAS, which won the most seats of any single individual party, there are many Malay voters who abhor the corruption-tainted UMNO but also do not agree with the PH’s reform agenda. The presence of these conservative Malay-Islam voters also explains the PH governments’ hesitation to proceed with political liberalization.

Is it inevitable that the authoritarian regime created by the BN will remain firmly entrenched? While it may be difficult to rapidly reform the apparatus of authoritarianism in Malaysia, it is important to point out several positive changes since 2018. First, anticorruption has become the norm. UMNO’s significant loss of seats in the last two elections was due to voters’ rejection of Najib and Zahid, leaders whose images are severely tainted by corruption charges. As a response to anticorruption sentiments, subsequent administrations have required ministers to disclose their assets, and Anwar has demanded further transparency. The cost of corruption is clearly higher than before.

Besides, reforms such as the Anti-Hopping Act, which requires MPs to recontest an election if they switch political parties, and the early implementation of the lowering of the voting age were also realized under the PN-BN coalition. This is due to the Memorandum of Understanding on Transformation and Political Stability agreed to by both government and opposition parties during the Ismail Sabri administration (2021–22). This document committed opposition parties to not oppose important bills such as the budget in exchange for parliamentary and judicial reforms. It is worth noting that the BN, the very architect of the authoritarian apparatus, initiated the institutional reforms by accepting the PH’s reform agenda—albeit for its political survival.

The rise in the last election of PAS, whose supporters included many young Malays, and Anwar’s reluctance to swiftly reform the authoritarian apparatus have certainly disappointed liberal voters. Nevertheless, we should take note of the fact that the unprecedented crisis in Malaysian politics somehow fueled reform thrusts: The 1MDB scandal prompted the subsequent government, irrespective of partisanship, to implement asset declaration; and unstable government following the extra-institutional change of government brought about crossparty cooperation for the Anti-Hopping Act, among others. Further reforms in Malaysia remain a possibility.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Malaysia’s new Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim after prayers at a mosque in Putrajaya on November 24, 2022. © AFP/Jiji.)