The Persistence of Authoritarian Regimes and Asia’s Long Road to Democracy

Prospects for Expanded Democracy in a Post-Lee Singapore

World- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

The Curse of Lee Kuan Yew’s State-led Development Model

From the nineteenth century, the Malay Peninsula was a critical node in the British Empire’s global trade network. The city of Singapore played a particularly prominent role. However, forced to separate from the Federation of Malaysia in 1965, Singapore gained its independence at the same time it lost its resource hinterland. These were challenging circumstances for the small city-state. Lee Kuan Yew, Singapore’s “founding father” and its first prime minister, responded by establishing governance and economic development models characterized by elitism, meritocracy, realism—and authoritarianism.

On the surface, Singapore’s political system is characterized by the rule of law, the separation of powers, and parliamentary democracy. In reality, the People’s Action Party has manipulated the electoral system to secure and sustain overwhelming dominance in Singapore’s unicameral parliament, effectively establishing a political dictatorship that has endured since the 1960s. The PAP has supplemented its hold on power by suppressing the political opposition through the blatant use of restrictions on speech and other social freedoms.

This extensive control over society has allowed the Singaporean government to place an excessive emphasis on competence, efficiency, and even eugenics in the social sphere. It has often adopted inhumane policies on population control, education, language, human resources, and urban design. Economically, Singapore adopted a form of “state-led capitalism.” While Singapore is open to foreign capital to sustain economic growth, employment, and innovation, key sectors of the economy are controlled by a group of public enterprises backed by government funds. Meanwhile, the government has only undertaken redistribution polices when absolutely necessary prior to the 2010s.

Singapore has nevertheless steadily achieved the trappings of a modern nation using this model: flexible government administration, long-term economic growth and sound finances, social order, and a certain level of social security for its citizens. Lee Kuan Yew was succeeded by Goh Chok Tong in 1990 as Singaporean leader, while Lee Hsien Loong, Lee Kuan Yew’s eldest son, took over the leadership in 2004. Lee Kuan Yew remained a pervasive but hidden influence until his passing in 2015, and the Singaporean government continued pursuing policies characterized by state-led economic development and authoritarian governance after Lee resigned from the premiership.

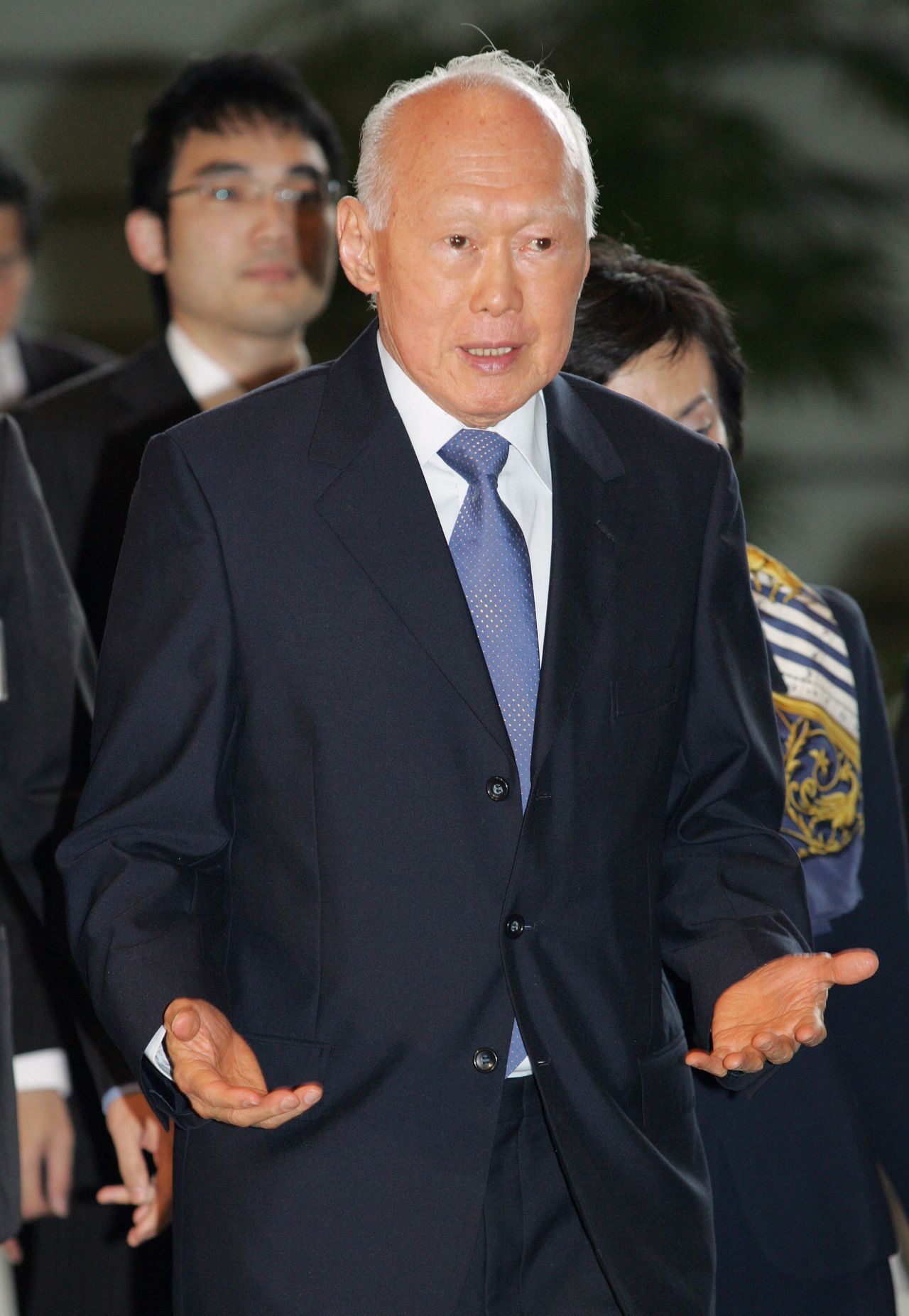

Former Singaporean Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew, photographed in May 2007. (© Jiji)

Prime Ministers of Singapore

| Lee Kuan Yew (1965–90) | |

| Goh Chok Tong (1990–2004) | Former Prime Minister Lee appointed to the advisory senior minister cabinet position |

| Lee Hsien Loong (2004–) | Prime Minister Goh moves to the senior minister role; former Prime Minister Lee becomes minister mentor (both resigned from the cabinet in 2011) |

Social Transformation and Societal Contradictions

As Singapore entered the twenty-first century as a nation transformed in these ways, the divergence between Singapore’s traditional governance and economic models and societal expectations only widened. For example, as a consequence of restrictive eugenics and population-control policies dating back to the country’s founding, demographic change in Singapore resulted in a rapidly declining labor force. The number of immigrant workers introduced to mitigate this outcome jumped from 130,000 in 1980 to 1.3 million in 2010—about 25% of the total population. This contributed to social discord as cascading problems ranging from employment to housing access to price increase precipitated public dissatisfaction. Meanwhile, even as per capita GDP exceeded the equivalent of $40,000 in 2010, the degree of redistribution to Singapore’s residents remained limited, and people became increasingly aware that they were not sharing in the benefits of national development.

Furthermore, the internet, including social media, radically undermined the government’s information control policies as people began to regularly access sources of information other than government-endorsed media. The younger generation in particular have been exposed to ideas and readily share opinions that challenge the conventional Singaporean governmental and development models. The diversification of values is now irreversible, and a steadily growing emphasis on the collective “will of the people” has emerged in political discourse.

Lee Kuan Yew had long believed that the government could manipulate and control the people with sticks and carrots, but this governance approach has been completely undermined by technological innovation. While some in Singapore’s leadership had already recognized this reality entering the 2010s, a fundamental revision of the governance model would have meant rejecting Lee Kuan Yew’s model. With Lee still exerting covert influence over Singapore’s politics, not even his son (Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong) could undertake overly progressive reforms.

The 2011 Elections as a Turning Point

Ironically, the catalyst for change came from the exercise of parliamentary democracy. In the 2011 parliamentary elections, public dissatisfaction surfaced, and the PAP’s share of the vote fell to an all-time low of 60.1%. The opposition parties gained six seats, well above the customary two seats it has been “allowed” since independence. Given an electoral system that favored the PAP, and restrictions suppressing opposing political voices, this outcome represented a substantial defeat for the regime.

In Singapore’s 2011 presidential election another breach of custom took place when four candidates ran for the presidency. Except for 1993, a single candidate has won the presidential vote uncontested since independence. Furthermore, former Deputy Prime Minister Tony Tan of the ruling party only prevailed by a meager 0.34% vote difference.

This series of results shocked the ruling elite into realizing that the traditional political approach was putting their hold on power at risk. The key Singaporean political principles of “pragmatism” and “meritocracy” quickly kicked into gear, and then Prime Minister Lee initiated a fundamental course correction. In his speech following the elections, Prime Minister Lee acknowledged that the government should change alongside society and the people, and that the political system needed to adapt and accept diverse opinions. Following this, then Minister Mentor Lee Kuan Yew and Senior Minister Goh Chok Tong both resigned their advisory cabinet positions that they had held on to since stepping down from the premiership. Four years later, in March 2015, Lee Kuan Yew passed away, symbolizing a clean break from the “old Singapore.”

Singapore’s Gradual Liberalization

Since 2011, the Singaporean government has presided over significant modifications to its governance model. For example, it rethought its unilateral pursuit of national economic power and instituted policies that address resident’s lifestyle concerns relating to treatment of foreign labor, employment, housing, infrastructure, and prices. It has also more aggressively redistributed income to those in need and rapidly expanded social welfare and public subsidies. Although these measures have had side effects, Prime Minister Lee emphasized in August 2013 that “there is no going back, even if the path taken is different from the one that guided us in the past.”

However, full liberalization remains elusive as social control has continued. For example, online news sites, which have begun to influence public opinion, have been subject to regulations such as the 2019 Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act and official and unofficial pressure on media owners. To avoid a repeat of the situation in the 2011 presidential race, the government also restricted the conditions for running in the 2017 election. The PAP’s preferred candidate won without requiring a runoff.

While not as intense as during the Lee Kuan Yew era, restrictions on the freedom of assembly and pressure on opposition parties and activists have continued. However, as public awareness and societal values change, the administration remains cognizant of the need for further reform, resulting in increasingly less tolerance of abuses of power in government.

One example of the Singaporean government’s increased political flexibility is its response to increasing social acceptance of homosexuality. Lee Kuan Yew’s strongly antihomosexual ideology meant that the nineteenth century colonial-era criminal penalties for sex between men (Penal Code 377A) remained on the books in Singapore after its independence. When an organization called “Pink Dot” began annual rallies in 2009 to support Singapore’s LGBT community, it faced obstruction by the government and hostility from religious groups. In August 2022, however, Prime Minister Lee announced that he would repeal the law, citing changing societal values.

Generational Change after the “Lee Family” Era

In parallel with changing societal and political elite awareness, Prime Minister Lee has accelerated succession preparations. He has promoted the training and promotion of the “fourth generation” of political leaders. Unlike his father, Prime Minister Lee deserves high praise for embracing an approach to succession that rejects hereditary and patriarchal principles. However, whether one is a member of the elite or an everyday resident, or pro- or anti-PAP in political orientation, Singaporeans are apprehensive about life without a “Lee” in the top position.

The success or failure of Singapore’s next leadership succession—one that will not take place in the charismatic political shadow of a Lee—is highly dependent on whether the next prime minister can bring together a team of “fourth generation” leaders. After several years of behind-the-scenes work, the oldest “fourth generation” minister, Heng Swee Keat (former finance minister and now deputy prime minister), was informally appointed as Prime Minister Lee’s successor in November 2018. However, this selection was decided by a small group of top-tier elites, in contravention of new political ideals emphasizing “the will of the people.”

This process, alongside lukewarm impressions of Heng’s suitability, prevented him from gaining popularity among a public accustomed to the stability and strength provided by the Lee father and son combination. The July 2020 parliamentary elections then became a vote of confidence in the choice of successor. The opposition gained a record 10 seats, while the PAP’s share of the vote languished at 61.2%, its third lowest ever. Moreover, Deputy Prime Minister Heng tried to assert himself during the election by changing his constituency to one that was expected to be hard-fought. This backfired as he only prevailed over the opposition party candidate with a 6.78% difference in vote share. In April 2021, Heng himself made the unprecedented announcement that he would not succeed Prime Minister Lee, and in April 2022, after much back-and-forth, Minister of Finance Lawrence Wong was unofficially anointed as Singapore’s next prime minister.

Singaporean Hopes for the Future

Wong has a civilian background, and his policy stances are pragmatic. He is realistic and adapts flexibly to changing power balances in politics. In my view, he is suitable because he meets the following requirements: (1) He is not a hereditary member of the Lee family; (2) he is not a member of the military elite, and therefore the national armed forces will not gain political influence; (3) being 50 years old, he is young enough to serve for at least the customary 10 years; (4) he is pragmatic and possesses a flexible sense of political balance; and (5), he is capable of organizing and uniting his colleagues. Wong became deputy prime minister in June 2022, and the consensus that he will be the next prime minister is now rapidly solidifying, both domestically and internationally.

As public attitudes change, the acceptance of diversity grows, and opposition parties steadily expand their presence, this next “fourth generation” leadership will need to pay closer attention than ever to the will of the people. On the other hand, many Singaporeans also believe that an overly rapid transformation of Singapore’s political process could have a significant negative impact. As long as Singaporean traits of pragmatism and balance prevail, the PAP losing the majority—a change in government—is unlikely to happen in the short to medium term. However, there is no likelihood of a return to absolute domination by Singapore’s top elites as was the case in the past. Although reform has taken place slowly and incrementally over the last decade in consideration of political reality, the transition to an “open society” is irreversible.

These developments in Singapore are remarkable given that many neighboring Southeast Asian countries have failed to develop healthy democracies despite deep-rooted resentment regarding the role of money, cronyism, and corruption in their politics. In fact, it appears that a preference for toughness has resulted in authoritarianism making a comeback. Therefore, in relative terms Singapore’s gradual but progressive transition to a mature democracy and liberal society is a noteworthy development. Of course, it will take time and there is still a long way to go to realize the transition to an “open society” and to a “fifth generation” of even more progressive leaders. But when it is achieved, Singapore can truly tout its success story.

(Translated from Japanese. Banner photo: Singapore’s Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong addresses the press after meeting US Vice President Kamala Harris at the White House, March 29, 2022. © AFP/Jiji News).