India’s March Toward Autocracy

Collaboration and Confrontation: Geopolitics, Global Affairs, and the India-China Relationship

Politics- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Two Global Giants Rise

Perhaps the biggest development in global geopolitics in the twenty-first century is the emergence of China and India. In 2023, India become the world’s most populous country at 1.429 billion people, overtaking China’s 1.426 billion. Together they account for about 35% of the global population.

Both countries have also experienced substantial economic growth during the current century. China has experienced the most persistent success, dating back to its “reform and opening up” policies of the late 1970s. Greatly assisted by its admission to the World Trade Organization in 2002, China passed Japan in 2010 to become the world’s second largest economy only two years after hosting the 2008 Summer Olympics. India began liberalizing its economy somewhat later than China, in 1991, but by the mid-2000s it also began to enjoy high rates of economic growth. It became the world’s fifth largest economy in 2022.

Building on this economic growth and modernization, both nations have also enhanced their military power. SIPRI, the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, ranks China second (estimated at $292 billion) and India fourth ($81 billion) in global military spending, as of 2022.

On their own, India’s and China’s rises would be significant stories. It is also important, however, to consider the relationship between these two emerging powers and the implications for global geopolitics. Bilateral relations have certainly been plagued by border tensions and competition for influence in Central and South Asia, but there is more to the relationship than confrontation. Below, I look at the historical context of India-China relations and the impact the evolving relationship could have on future global affairs.

Deepening Economic Cooperation Despite Border Tensions

Following World War II, India gained independence from Britain in 1947, while the Chinese Communist Party established the People’s Republic of China in 1949. India and China initially forged friendly and forward-looking relations based on a vision of solidarity with other countries in decolonizing Asia and Africa. This optimism was, however, short lived.

Relations turned sour following the Tibetan uprising of 1959. Indian leaders granted the fourteenth Dalai Lama asylum in India, where he established a shadow Tibetan government. Three years later, China’s sudden annexation of disputed territory in India’s northeast caught New Delhi by surprise, resulting in military defeat for India. Bilateral relations remained cool for the rest of the Cold War.

As the Cold War wound down in the 1980s, border talks resumed at an administrative level. Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi then visited China in 1988—the first visit by an Indian premier in 34 years. These developments were the basis for progress on border issues and a general improvement in relations during the 1990s. This was temporarily derailed when India conducted a nuclear test in 1998 and Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee cited China as a threat in a letter to US President Bill Clinton. In 2003, however, Prime Minister Vajpayee visited China, and signs of compromise emerged with the appointment of a high-level special representative to discuss border issues. China then recognized India’s de facto possession of Sikkim, while India recognized that the Tibet Autonomous Region is an inherent part of Chinese territory. This established the foundation for Beijing and New Delhi’s “Strategic Cooperative Partnership for Peace and Prosperity” promulgated during Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao’s 2005 visit to India.

However, incursions into Indian controlled territory by Chinese troops began in 2008 and were widely reported in the Indian media, and a military stand-off occurred in 2013, reigniting a sense of caution toward China. While Narendra Modi invited Xi Jinping to India in 2014 following his inauguration as India’s prime minister, and the two new leaders agreed to strengthen relations, both militaries continued to face off against each other in the border regions. In 2017, the Doklam standoff took place in Bhutan between the two armies as Chinese troops attempted to build a road in territory claimed by Bhutan. Conflict then broke open in 2020 in the Galwan Valley in India’s northwestern Ladakh region when China objected to India’s road building activities along the Line of Actual Control. The armed clashes resulted in deaths for both militaries.

These border tensions have not, however, dampened economic relations between China and India. Total bilateral trade volume tripled in the space of 15 years, from $38 billion in 2007 to $113.8 billion in 2022. Since 2013, China has sat alongside the United States as India’s biggest trade partner.

The economic relationship, however, is somewhat one-sided, with India importing more from the PRC than it exports. The trade deficit has also expanded at the same rate as the growth in overall trade. In response, India introduced investment restrictions on Chinese companies. It also banned TikTok and other Chinese smartphone apps due to security concerns.

India’s Geopolitical Environment and China

New Delhi’s concerns extend beyond China’s economic influence over India: China’s growing influence in South Asia and the Indian Ocean region has also stimulated suspicion of China’s geopolitical motives. The Belt and Road Initiative announced by Xi Jinping in 2013 represents China’s vision for regional development based on financial cooperation and the implementation of large-scale infrastructure projects in countries surrounding India. Most worrying for New Delhi is Beijing’s cooperation with Pakistan. Pakistan and India have fought three wars since independence, but Beijing has moved increasingly closer to Islamabad through the implementation of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor. Connecting China’s Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region with the port city of Gwadar on the Arabian Sea, the CPEC also runs through the Kashmir region, which is under Pakistan’s control, but over which India claims sovereignty.

India also has its own regional development initiatives. The Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation held its first summit in 2004 and now includes Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Myanmar, Nepal, Sri Lanka, and Thailand. The Indian Ocean Rim Association, comprising 23 Indian Ocean coastal nations from South Africa to Australia, held its first summit in 2017. New Delhi has not, however, always found the regional geopolitical environment favorable.

For example, India’s “Act East” policy aimed to deepen economic ties with Southeast Asia through connectivity infrastructure. Myanmar’s 2021 coup forced a rethink of this policy, although the Japan-backed port at Matabari—Bangladesh’s first deep sea port—is now attracting New Delhi’s attention. To India’s west, a plan to develop a multimodal transport corridor focused on Chahbahar Port in eastern Iran (and near Pakistan’s Gwadar Port) promised to facilitate India’s access to Afghanistan and Central Asia and bypass Pakistan. While the port began receiving Indian goods in 2017, Iran and India are now renegotiating the broader connectivity project following the Taliban regime’s return to power in 2021.

At the same time, India has not neglected its relations with the traditional great powers. India’s strategic cooperation with the other “Quad” countries of Japan, the United States, and Australia has accelerated since 2017. India has also expressed support for the Free and Open Indo-Pacific vision driven forward by Japan but embraced by various other nations in the region to constrain Chinese assertiveness.

Coexistence of Conflict and Cooperation

Despite this geopolitical maneuvering and bilateral tensions, New Delhi has not disengaged from China. India remains a committed member of regional and global plurilateral frameworks led by Beijing. In 2005, India became an observer at the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, which includes Russia, China, and Central Asian countries. (It became a full SCO member in 2017.) India joined China in the BRICS intergovernmental organization which began holding summits in 2009. India was also a founding member of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank established in 2015.

At the global governance level too, China-India relations are characterized by a mixture of competition and collaboration. For example, India wants a permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council. While the United States, Russia, the United Kingdom, and France all basically support New Delhi’s position, China has held back its support. Current permanent UNSC members have veto rights over all proposals, and if India or other major nations such as Brazil, Japan, and Germany were to become permanent members then a more radical overhaul of the UNSC would likely take place. This could dilute China’s institutional privileges and relative influence in the United Nations.

Given these circumstances, India’s emphasis on the G20 and the extraordinary energy it has devoted to its presidency in 2023 is notable. It reflects India’s determination that it offers a particular type of global leadership value—for example, India is able to engage constructively with both major developed countries and emerging economies and bring them together.

Traditionally, China has positioned itself as the leader of the “Global South” of non-Western developing and emerging economies. However, India hosted a virtual “Voice of the Global South Summit” in January 2023. As India was the president of the G20 in 2023 and New Delhi the host of the summit, the Indian government positioned itself as a conduit for the voices of Global South nations into G20 proceedings. At the September summit, India proposed and successfully achieved the accession of the African Union to the G20 grouping, in addition to shaping the G20 Joint Declaration to reflect Global South concerns on food and energy issues. India then held a second virtual Voice of the Global South Summit in November.

While China did not hold a similar summit, Premier Li Qiang attended the “G77+China” summit in Cuba immediately following the G20 Summit. Here the Chinese side emphasized its past development cooperation achievements with more than 160 countries. The Third Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation was then held in October in Beijing, allowing President Xi Jinping to reaffirm Beijing’s desire to work with other countries to realize modernization and economic development.

While there may be competition for leadership and influence, India and China’s appeal to non-Western nations is predicated on a similar desire to assist other emerging nations in their rise. India and China are also “fighting together” in some global fora. In 2021, when climate change and coal-fired energy infrastructure was discussed at the Glasgow COP26, India and China actually formed a united diplomatic front. While the conference host Britain and the rest of Europe pushed for a “total phase-out” of coal-fired energy generation, India and China successfully limited the discussion to “phased reductions.”

This is a clear indication that the balance of power in the world is changing. In the future, it is likely that India and China will find common cause in other areas of global affairs. If so, they will exercise a substantial influence over the direction of future global governance and geopolitical outcomes.

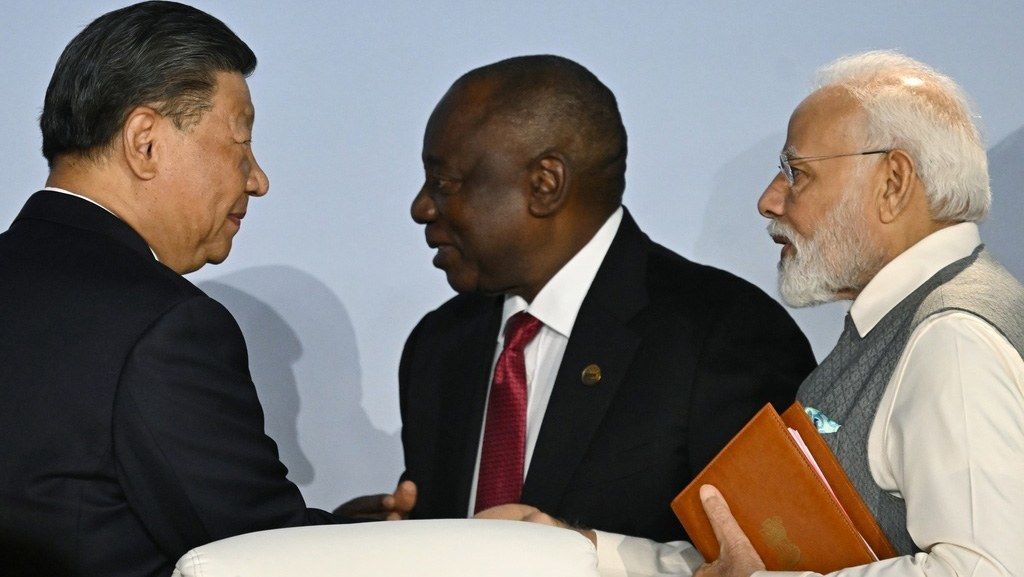

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Chinese President Xi Jinping, at left, and Indian Prime Minister Modi, at right, attend a press conference at the BRICS summit. In the center is South African President Ramaposa. Johannesburg, August 24, 2023. © Sputnik/Kyōdō.)