Building a Future for Japan’s Fisheries Industry

Economy Environment- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

A Precipitous Drop in Marine Resources

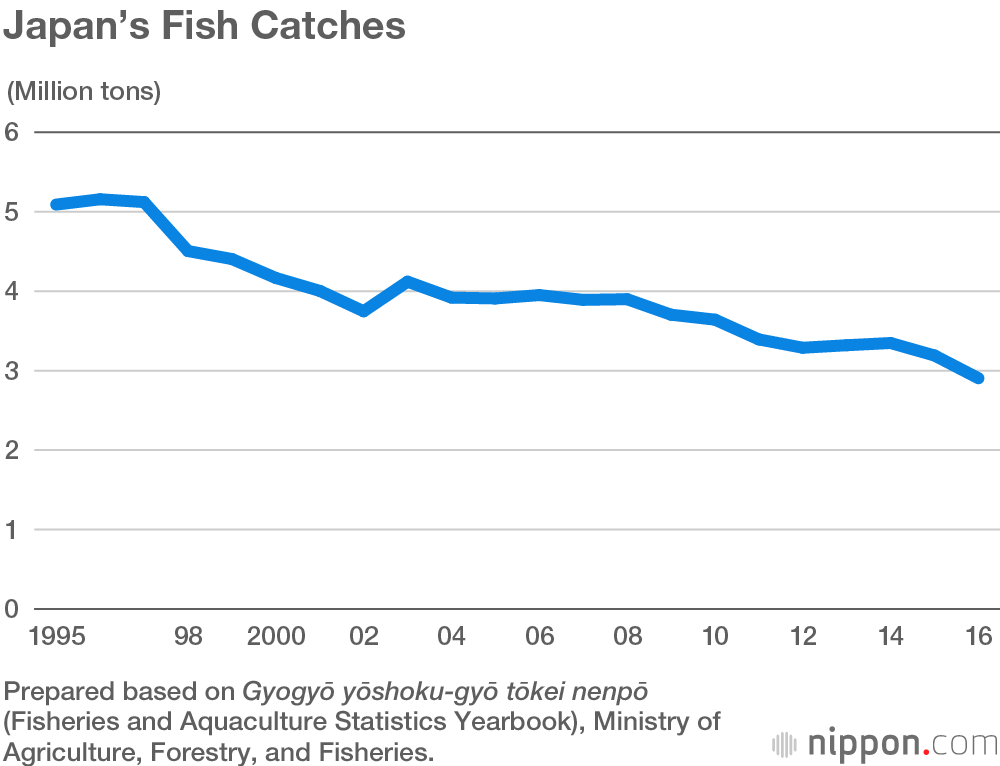

It’s well known that catches of bluefin tuna, eel, Pacific saury, and other species have been poor lately. This may sound as though it’s a problem pertaining just to this year, but the truth is that Japan’s catches, excluding pelagic fishery, have been in straight decline for over 20 years and are on track to fall to zero by 2050. This is not just happenstance; structural issues are to blame.

Japan once had the most competitive fishing industry in the world. For 20 years, from 1972 to 1991, Japan ranked first in catch volume. But catches started declining markedly in the 1990s, due in part to the precipitous drop in the sardine population. Sardines had reproduced explosively since 1972, but beginning around 1989 the egg survival rate began to decline; by the second half of the 1990s almost no sardines were being caught. Most researchers attribute the decline in the sardine population to natural factors. Although stocks have begun to recover somewhat in recent years, Japan’s fishery productivity has continued to drop because marine resources other than sardines are in decline across the board.

According to a study by the Japan Fisheries Research and Education Agency, the Fisheries Agency’s research arm, many of Japan’s marine resources are at low levels. In a Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries survey of fishers, 90% of respondents said they felt that resources were scarcer; only 0.6% believed that resources were increasing. Even if Japan wanted to increase catches, the reality is that there are no fish in its own exclusive economic zones. The result: catches are dropping, fewer people are active in the profession, and fishing communities are aging and depopulating.

The Price Paid for Overfishing

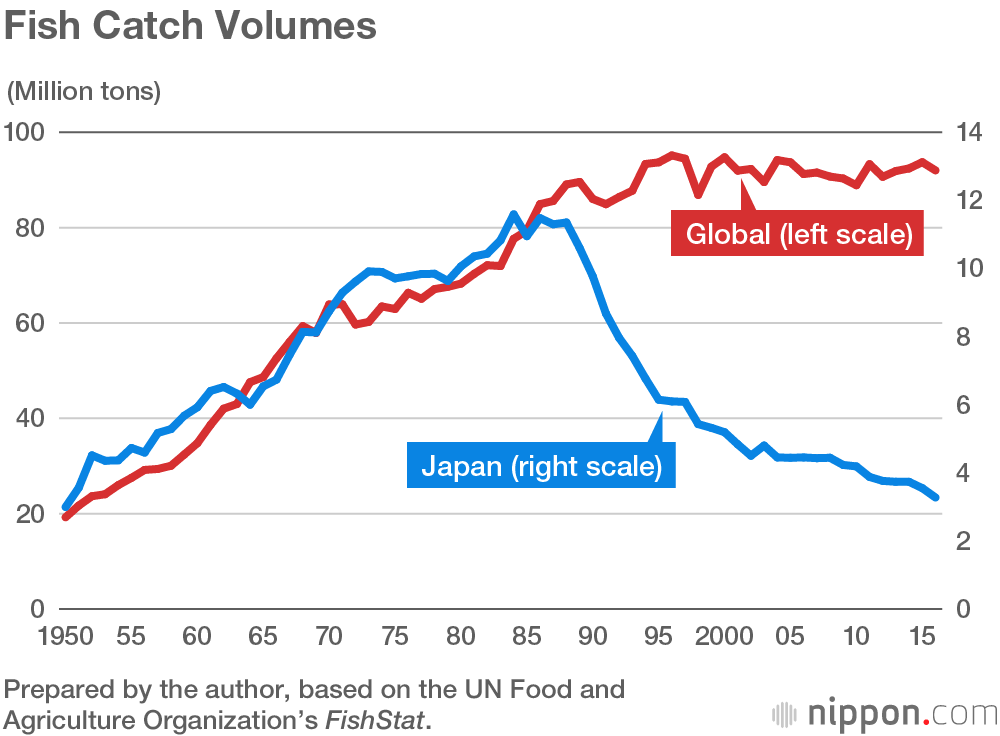

The figure below charts changes in wild catch volume globally and for Japan. Both Japanese and global productivity grew through the 1970s, but only for Japan did catches begin dropping after the 1990s.

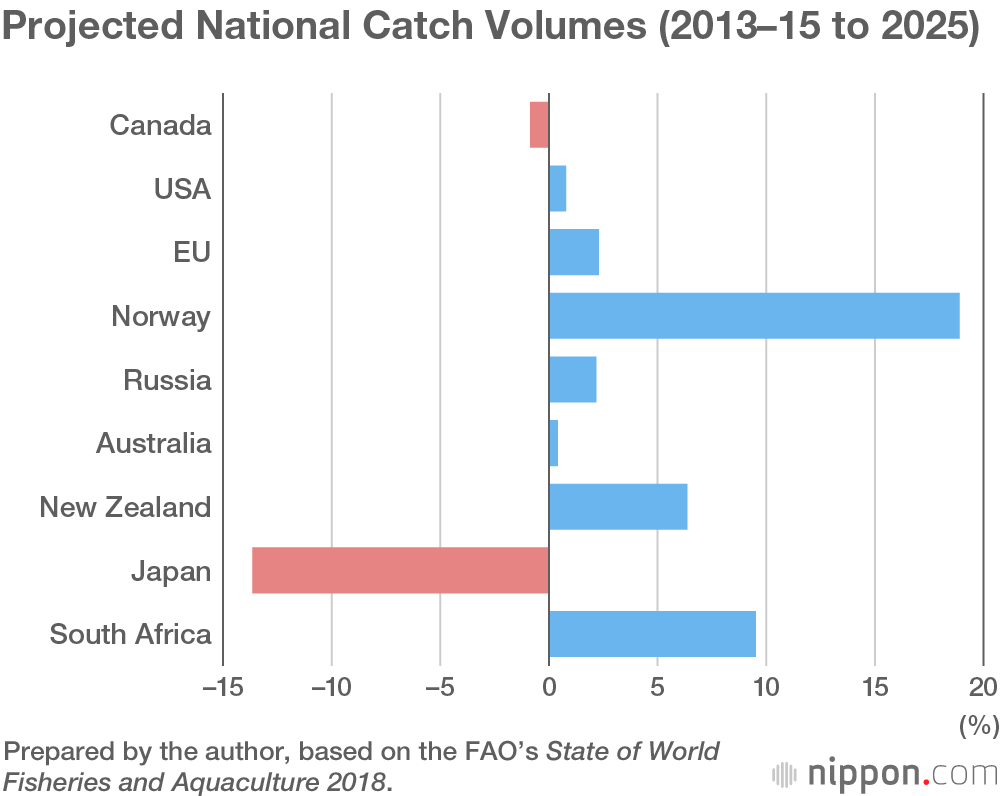

At the global level, wild fish catch volumes are high and holding steady. Aquaculture productivity is growing rapidly at 6% per annum in the rest of the world, although it is down in Japan. According to a forecast of future fisheries productivity among the main fishing nations by the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization, most economies, advanced and developing alike, will increase productivity; Japan is the only country for which a major drop in productivity is foreseen. Why is Japan, once a major fishing nation, performing so poorly now? A look back at the history of Japan’s fishery in the postwar period may yield some answers.

Government policy encouraged the growth of the fishing industry as a means of alleviating food shortages after World War II. At the time, there were no EEZs, and Japanese fishing fleets could take all the fish they wanted up to 5 to 8 kilometers from any other country’s shores. The seas lying offshore from countries, mainly developing economies, without a robust fishing industry of their own held an untold wealth of marine resources, and Japan’s fishing industry continued to expand, under the slogan “from coastal to offshore; from offshore to open ocean.”

Sustainability of resources was not top of mind in Japan’s fishing industry at the time. Fleets would fish in one spot until there was nothing left to catch, and then move on to other fishing grounds, catching different species. The government supported the development of unexploited marine resources and new fishing grounds. At the industry’s peak, Japanese fishing boats could be found in rich fishing grounds off South America, Alaska, New Zealand, Africa, and many other parts of the world. Japan was the winner in the international “first come, first served” fishing stakes.

But starting in the latter half of the 1970s, when countries with coastlines began establishing EEZs extending 200 nautical miles (about 370 kilometers) from their shores, it became impossible for Japan to actively exploit other countries’ fishing grounds. In the intervening years, Japan continued haphazardly catching fish where it could, depleting fish stocks in its own EEZ and pushing the industry into decline.

Fishing without concern for sustainability led to a drop in fish stocks, and it was only a matter of time before this rendered the industry unviable. Ensuring the sustainability of marine resources requires restrictions on catches to preserve sufficient stocks of spawning adults. And to make profits without increasing catches, more valuable fish must be caught. In the days of unimpeded competition, fishers vied to be the fastest to catch the most fish. That was a practical approach then, but in the EEZ era, leaving enough adult fish to make future fishing profitable is the way to go.

Impose Quotas to Control Overfishing

Quotas are needed to ensure the sustainability of marine resources, but they are not enough. In the early days, quota management simply meant setting limits to catches. Once the designated quota had been reached, fishing stopped. That only heated up the race to catch the most fish, so fishers ended up catching younger and younger fish, which negatively affected productivity. To catch more fish faster than their competitors, fishers outfitted their boats with more powerful engines and invested in fish detectors, sonar systems, and other fish-locating equipment. When they could not find large fish, they scooped up even fry, thinking that they could at least offset part of the cost of fuel with such marginal catches. But continually upgrading equipment ended up costing so much that it became impossible to turn a profit.

Setting individual quotas is effective for overcoming this problem. Assigning quotas to individual operators restrains competition to catch ever younger fish. Since they do not need to catch fish before their rivals do, fishers can fish when their catch reaches peak value. They will in fact avoid catching fry, to give young fish a chance to grow. This helps boost the value of catches and make fishing businesses more profitable.

Fishing nations such as New Zealand, Iceland, and Norway introduced individual quotas in the 1980s and succeeded in making fishing a growth industry. The individual quota system has also been adopted by the United States, the European Union, Peru, and many other countries. Japan, having yet to adopt individual quotas, is the outlier in this respect, and its declining catches and fading industry can be explained by its failure to more thoroughly regulate fishing.

Fisheries Act Revised at Long Last

For the first time in 70 years, revisions to the Fisheries Act were enacted during the extraordinary session of the Diet in December 2018. These revisions finally put into place government authority to regulate fishing.

Article 1 of the current Fisheries Act defines its purpose as “to establish a basic fisheries production system in which fisheries adjustment organizations mainly consisting of fishery managers and fishery employees can be operated for systematic utilization of waters, to thereby enhance fisheries productivity and also to democratize the fishing industry.”

The original Fisheries Act, reflecting the need to ramp up food production, dates from the days of postwar food shortages. Its main focus was on developing fisheries productivity, and nowhere was sustainability of fish stocks mentioned. The law served its purpose then but had become outdated and ineffective.

The 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea acknowledged countries’ right to establish 200-nautical-mile EEZs off their coastlines. At the same time, it made those countries responsible for managing the marine resources within their EEZs. Many fishing nations revised their fisheries laws at that time, strengthening the legal framework for regulating the industry.

In Japan, the revised act now adds the words “and ensure sustainable use of marine resources” to the purpose of the law. Article 6 further states that it is the government’s responsibility to preserve and manage marine resources, as follows: “In order to further develop fishery productivity, the central government, along with the prefectures, shall be responsible for appropriately conserving and managing marine resources and shall take the necessary measures to prevent and resolve disputes over the use of fishing grounds.”

Additionally, quotas, which now apply to only eight species, will be expanded to cover other species, and the government will also introduce the individual quota system for all fishing. Japan is finally taking steps to adopt a system used by other developed fishing nations for making fishing a growth industry.

In terms of area, Japan has the world’s sixth largest EEZ, which includes some of the richest fishing grounds anywhere. If Japan can harvest its marine resources sustainably, it can reclaim its place among the world’s premier fishing nations. The revised Fisheries Act is a step in that direction, but the future is cloudy. Quotas already introduced for bluefin tuna have been flouted by some operators who took far more than their allotted share. As a result, all fishing for bluefin tuna has been suspended for six years. That penalizes not just the offenders but also others who played by the rules and stayed within their quotas. Those aggrieved fishers have now filed suit against the government. The revised legislation is a start, but it remains to be seen how effectively it can be implemented.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: A Pacific saury catch being unloaded at Hanasaki Minato in Nemuro, Hokkaidō, on August 28, 2018. © Yomiuri Shimbun/Aflo.)