What TPP Means for Japan and the Global Economy

Economy Politics- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

The Turbulent Journey to TPP11

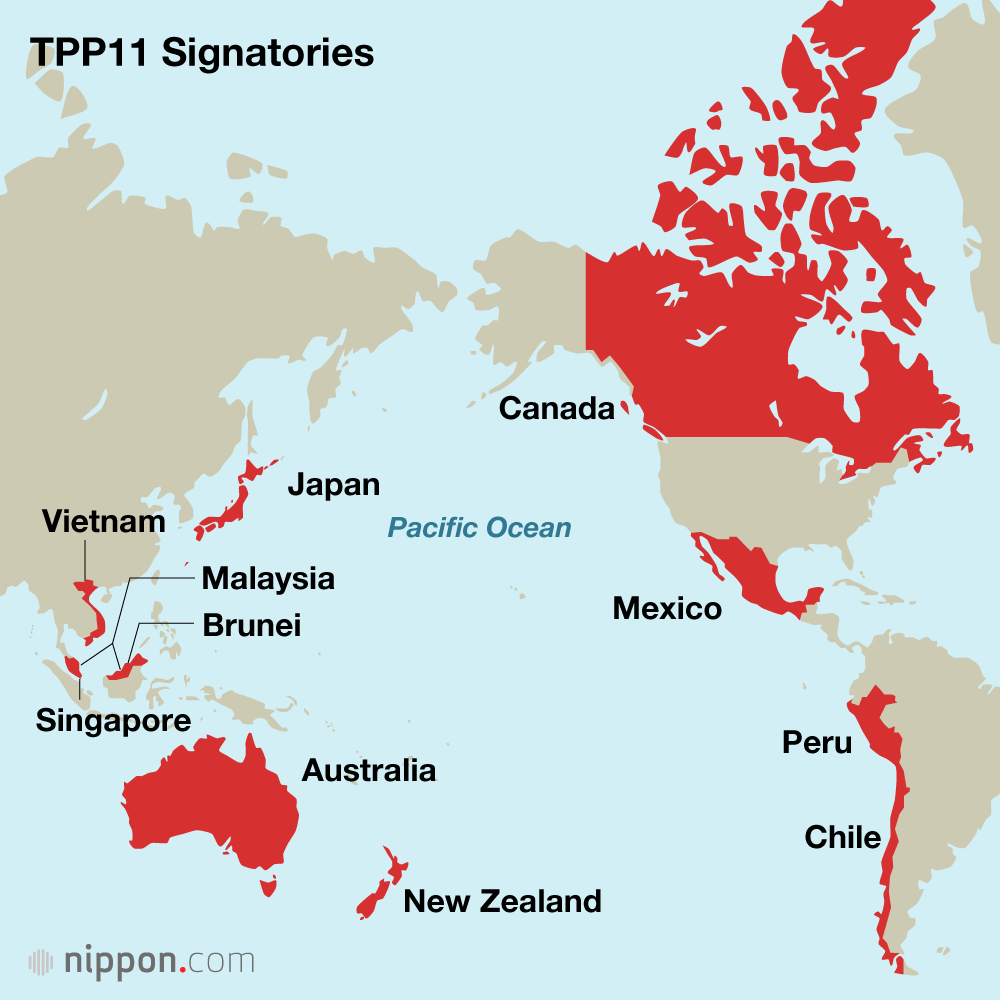

The Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership, also known as TPP11, took effect on December 30, 2018, creating a free-trade zone with some 500 million people, a combined GDP of about $10 trillion, and annual trade valued at about $5 trillion.

This agreement was preceded by the Trans-Pacific Partnership, which 12 countries including the United States agreed to in October 2015 and then signed in February 2016. Soon after taking office, however, President Donald Trump issued an executive order withdrawing from TPP, as he had promised to do while on the campaign trail. For TPP to take effect, it had to be ratified by 6 or more countries, whose combined GDP needed to be 85% or more of the total GDP of all 12 signatories. With the United States withdrawing from the agreement, it was widely believed that TPP was finished.

Without the United States, such developing countries as Malaysia and Vietnam believed TPP would lose half its meaning. For Canada and Mexico, meanwhile, renegotiating the North American Free Trade Agreement—also torpedoed by the Trump administration—had greater priority. Japan persisted in efforts to win over these countries, and an agreement in the form of TPP11 was finally reached in November 2017.

As the protectionist trade policies of the Trump administration took hold, Japan’s vigorous economic diplomacy gathered high acclaim. Japan hosted three of the four senior officials meetings (gatherings at the level of top trade negotiators) held in the final stage of negotiations after July 2017, including in the resort town of Hakone, near Tokyo. The leadership displayed by Japan was unprecedented and drew much attention.

A Model for Twenty-First Century Trade Agreements

While TPP11 is a compact agreement with only seven articles, Article 1 is used to incorporate the TPP as it was agreed to by 12 countries. In this manner TPP11 became the legal means for bringing TPP back to life.

Article 2 prescribes the suspension of the application of certain provisions, freezing 22 provisions that were added at the strong insistence of the United States during TPP negotiations. Half concern intellectual property. Provisions that gathered the strong interest of the United States, such as the eight-year data protection period for biologics and investor-state dispute settlement regarding investments, have been suspended.

Article 3 prescribes the agreement’s entry into force. Unlike TPP, only the number of ratifying countries was made a requirement, and the GDP criterion was eliminated.

Article 4 and Article 5 set forth rules for withdrawal and accession, respectively. Article 6 concerns the review of the agreement. If the original TPP is about to take effect, or when it is deemed unlikely to do so, the way TPP11 operates can be revised at the request of any signatory country. This can be understood as a provision added in the case the United States decides to rejoin the agreement. Article 7 states that the formally binding texts of the agreement are in English, Spanish, and French.

Elimination of Tariffs and Rules for Investments and E-commerce

What effects is TPP11 expected to have? Signatory countries have promised to eliminate nearly 100% of tariffs on manufactured goods, an industrial sector in which Japan excels. Countries receiving investments are prohibited from demanding technology transfers in exchange for investment authorization. The agreement also encompasses rules on e-commerce, an area unregulated by the World Trade Organization. These rules prohibit requirements for the transfer or access to source code or for computer servers to be sited locally in a given national market. State-owned enterprises are prohibited from negatively impacting the interests of other signatory countries through noncommercial assistance.

As the above should make clear, TPP11 is of great importance for Japan, a country that greatly depends on trade and investment. This is the reason TPP11 is being called a high-level “mega” free-trade agreement for the twenty-first century. As protectionist tendencies strengthen under the Trump administration, TPP11 taking effect at the end of 2018, followed by the Japan-EU Economic Partnership Agreement on February 1, 2019, have been extremely meaningful developments from the perspective of defending a free and open international trading system.

New Rules in TPP11

1. Facilitating Customs Procedures and Trade

One issue to be addressed through TPP11 was improving connectivity to increase the efficiency of crossborder manufacturing networks. The agreement secures the application of customs rules with predictability, consistency, and transparency, and it specifies the promotion of cooperation among signatory countries, the harmonization of international standards, the expediting of customs procedures, and access to administrative or judicial review.

TPP11 is expected to generate the following benefits.

a) Expedited customs clearance: Goods are released within 48 hours after their arrival to the extent possible.

b) Express shipments: Under normal circumstances, express shipments are released within 6 hours after submission of the necessary customs documents.

c) Advance rulings: Parties will be able to submit written requests for advance rulings on such matters as tariff classification and country of origin, thereby expediting customs clearance.

d) Automation: Parties will be able to electronically complete import and export procedures at a single entry point.

2. Investments

An important component of building crossborder manufacturing networks is the free flow of foreign direct investment. For this reason, the chapter on investment prescribes matters on the national treatment and most-favored-nation treatment of investments before and after their establishment. It also prescribes the fair and equitable treatment of investments and their full protection and security. Moreover, parties are prohibited from imposing performance requirements on investors, such as requiring local procurement or demanding technology transfers. In these ways, TPP11 goes further than the current Agreement on Trade-Related Investment Measures of the WTO.

For such federal states as Canada and Australia, many investment regulations are enforced at the regional level of government. The investment chapter of TPP11 includes a mechanism where parties are to enter into consultations regarding the nonconforming investment regulations of regional governments. The result is a better investment environment for investors.

3. Crossborder Trade in Services

TPP11 prescribes national treatment, most-favored-nation treatment, and market access for crossborder trade in services (supply mode 1), the consumption of services abroad (mode 2), and services supplied through the presence of natural persons (mode 4).

TPP11 covers all service sectors in principle and lists in an annex measures and sectors where the obligations for national treatment, most-favored-nation treatment, and market access are not applied (the negative-list method). With this approach, the current situation for regulations can be understood at a glance, and transparency, legal stability, and predictability are high. As such, this is viewed as a more user-friendly approach than the positive-list method taken in the General Agreement on Trade in Services of the WTO.

4. Temporary Entry for Business Persons

TPP11 prescribes the approval of the temporary entry of business persons from one signatory party to another, the conditions for temporary entry, and increasing the speed and transparency of application procedures.

New elements in TPP11 that were not part of GATS include ensuring the transparency of application procedures for immigration formalities; commitments on the provision of information, such as on changes in the conditions for temporary entry and typical time frames for processing applications; and commitments on the consideration of cooperation activities related to visa processing and border security.

5. E-commerce

Although the e-commerce market is expanding rapidly, e-commerce is not covered by WTO. With TPP11, comprehensive and high-level provisions on e-commerce were finally established. These provisions include the following.

a) No party shall impose customs duties on electronic transmissions between one party and another.

b) No party shall accord less favorable treatment to digital products produced in the territory of another party than it accords to other like digital products.

c) Each party shall allow the crossborder transfer of information by electronic means (including personal information) when this activity is for the conduct of business.

d) No party shall require an enterprise to use or locate computing facilities in that party’s territory as a condition for conducting business in that territory.

e) No party shall require the transfer of, or access to, source code of mass-market software owned by a person of another party.

In addition to the above, TPP11 also provides for the protection of e-commerce users and online consumers, securing an environment where consumers can use e-commerce with confidence.

6. Government Procurement

TPP11 prescribes rules for the procurement of goods and services whose value exceeds a relevant threshold by the procurement entities of a party’s government. Specifically, the agreement prescribes an open tendering procedure, tenders accorded with national treatment and nondiscrimination, and a fair and impartial procurement process.

Of the signatories to TPP11, Malaysia, Vietnam, and Brunei did not join the WTO’s Agreement on Government Procurement. Having made international commitments on government procurement for the first time through TPP11, Japan’s access to the government procurement markets of these countries has improved.

7. State-owned Enterprises and Designated Monopolies

When the state-owned enterprises and designated monopolies of TPP11 signatories make purchases and sales of goods and services, they must:

a) act in accordance with commercial considerations,

b) accord nondiscriminatory treatment to the enterprises of other signatories,

c) and not cause adverse effects to the interests of another party through the use of noncommercial assistance (grants or loans and other types of financing on terms more favorable than those commercially available) that is provided to any state-owned enterprises.

Meanwhile, country-specific annexes are used by signatory parties to list certain rules that do not apply to some of the activities of their state-owned enterprises or designated monopolies.

Rules specific to state-owned enterprises have not been a part of WTO agreements or the economic partnership agreements that Japan has previously concluded. The provisions of TPP11 have created an environment where foreign enterprises and state-owned enterprises can compete on equal terms, a landmark event in rule formation.

Trade Diplomacy Toward the Participation of China

In this manner, TPP11 achieves a high level of market access and establishes rules that cover the new trade policies of the twenty-first century. Future issues for the agreement are the expansion of member countries and the return of the United States. The true value of TPP11, though, will be tested by whether it can bring China into its framework.

The return of the United States and the participation of China are both difficult issues for the moment. It will be desirable for Japan to engage in strategic trade diplomacy to bring these two major countries within the rules of TPP11.

(Originally published in Japanese on February 20, 2019. Banner photo: Prime Minister Abe Shinzō, third from right, shaking hands with participants at the first meeting of the TPP Commission held in Tokyo on January 19, 2019. © Jiji.)