A National Conversation is Needed on the Purpose of the Consumption Tax Hike

Economy- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Raising the Consumption Tax to 10% Is Still Undecided

As I write this on May 7, the increase of the consumption tax to 10% on October 1, 2019, is still not finalized. Despite this situation, the fiscal 2019 budget has already been passed assuming this increase, and measures to extend greater social security benefits to all generations are being implemented.

For example, the Keidanren, the Japan Association of Corporate Executives, and the Japan Chamber of Commerce and Industry, Japan’s three major business organizations, have agreed to Prime Minister Abe Shinzō’s request to contribute ¥300 billion to a ¥2 trillion policy package the government will begin implementing in fiscal 2019. This package includes measures to eliminate waiting lists for nursery schools and to make preschool education free to the families that use it. As a result, member companies of these organizations have assumed an additional financial burden since April 1, the start of the fiscal year.

When the consumption tax is raised to 10%, the tax on food and beverages will be left at 8%. Companies are preparing for this change by updating cash registers and price labels and are reviewing the particulars of distinguishing between take-out and eat-in purchases with tax authorities. Repeated discussions have taken place on the reward points program for cashless purchases, and a final decision is nearing on such matters as the scope of eligible stores.

In this manner, preparations for a 10% consumption tax are well underway. The intentions of Prime Minister Abe and the Kantei, or Prime Minister’s Office, however, are still opaque. With a House of Councillors election scheduled for summer, there is the possibility of the House of Representatives being dissolved to hold a simultaneous election under the pretext of postponing the consumption tax’s rise for a third time.

Such a move by the Kantei would likely be ridiculed by citizens and companies. The consumption tax is paid by all consumers, with the tax liability falling on companies. With only six months to go, a final decision on raising the consumption tax has yet to be made. This state of affairs will provoke the suspicions of citizens about the reasons for the tax increase and will give rise to distrust in the tax itself. A prompt decision is needed.

Restoring Sound Public Finances or Strengthening Social Security?

The consumption tax is said to provide revenues to support an aging society, a description with the following two meanings. First, the consumption tax is an earmarked tax whose entire revenues go for social security expenditures, and the tax increase is intended to strengthen social security. Second, consumption tax revenues in themselves are insufficient to fully fund social security expenditures in Japan, and this gap is filled by deficit-financing bonds. By making up this deficit with tax revenues, social security can be made more stable.

Money is fungible, however, and the distinction between these two rationales is not entirely clear. Citizens will criticize the second rationale by saying that consumption tax hikes are only going to supplement the budget deficit (repair public finances) and are not strengthening social security. In other words, the government, in picking the rationale that suits the occasion to justify a tax increase, is creating mistrust in such increases.

In this context, it is useful to examine the integrated reform of the tax and social security systems agreed to by three political parties in 2012. In this reform, the consumption tax was raised from 5% to 10%, and the entire increase in revenues was earmarked for social security. However, 4 percentage points of the 5-point increase were allocated for stabilizing social security with the view to reduce the burden on future generations. In other words, such revenues were used to finance social security expenditures that had relied on government bonds. The remaining 1-point increase went for strengthening social security, such as fortifying healthcare, long-term nursing care, and childrearing.

From the perspective of citizens, since the 4-point portion would go for repairing public finances and not the strengthening of social security, they would not experience this as a benefit. This situation led Prime Minister Abe to announce that, while the consumption tax would rise to 10% as scheduled in October 2018, the ¥5 trillion in increased revenues would be divided roughly in half between (1) reducing the financial burden of education, support of the childrearing generation, and securing long-term care workers and (2) decreasing the burden on future generations (rebuilding public finances). In other words, one half, rather than four fifths, of the increased revenues from the 2-point tax hike would go for rebuilding public finances.

Should it be necessary to raise the consumption tax again, whether its purpose is to strengthen or stabilize social security (that is to say, restore sound public finances) will likely become the subject of discussion. Prime Minister Abe has expanded the use of the consumption tax to include education, such as free preschool education. Strengthening social security, free education, and the rebuilding of public finances are all matters of interest to citizens. Accordingly, this is an issue that should be debated in an easy-to-follow manner.

Needed: A National Conversation on Benefits and Burdens

In view of Japan’s economic and social situation, increasing the consumption tax beyond 10% is an essential choice for reducing the risk of budget deficits and for financing the growth of social security expenditures. The points at issue can be summarized as follows.

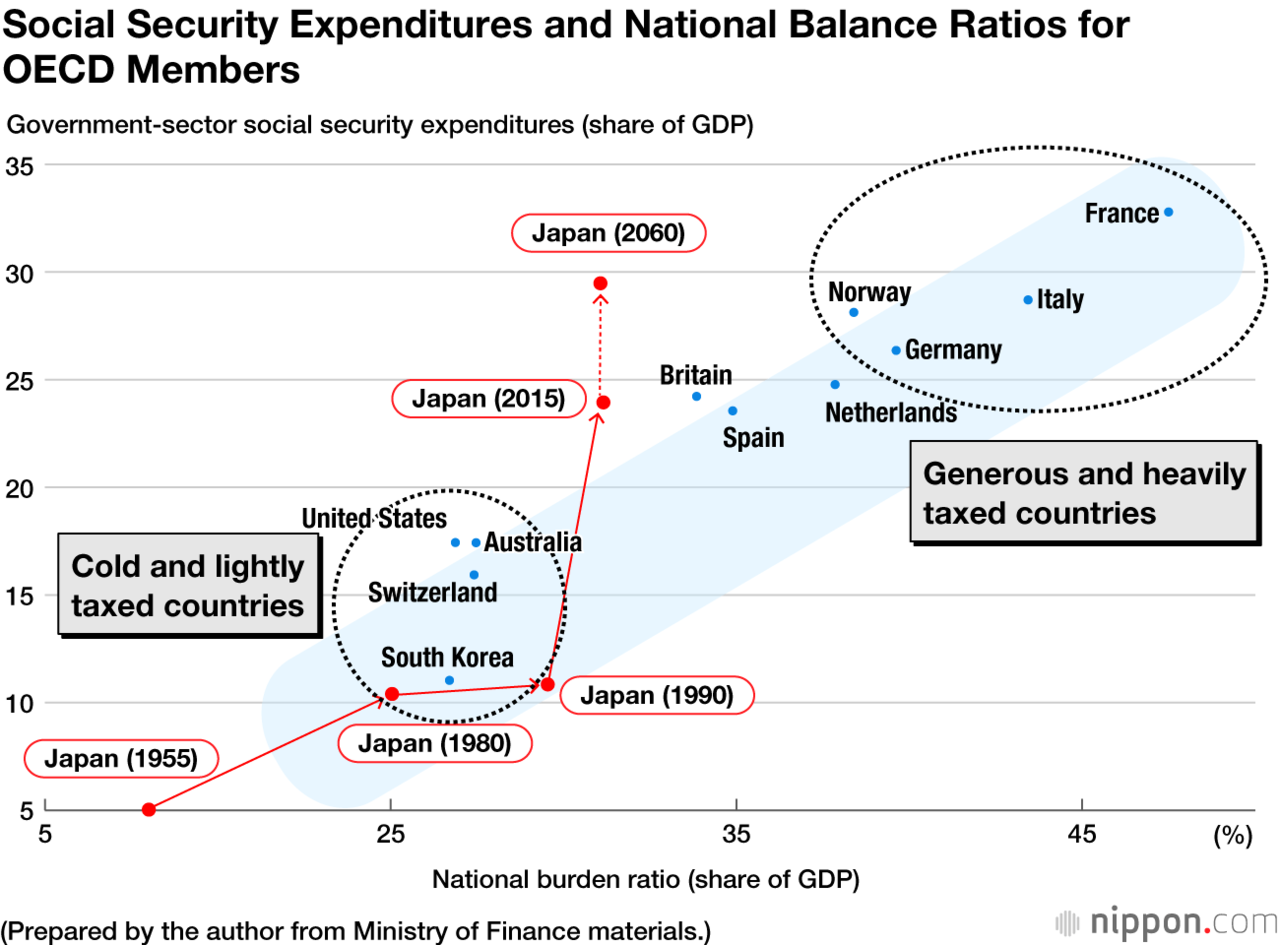

First, a national conversation is needed on benefits and burdens. The figure below, which compares the taxpayer burden and the size of social security expenditures of OECD member nations, reveals a distinct trend. Countries with large social security expenditures have a large taxpayer burden, and countries with small social security expenditures have a small taxpayer burden.

I have labeled the former “generous and heavily taxed countries” and the latter “cold and lightly taxed countries.” Japan diverges from this trend and is a generous and lightly taxed country. As a result, Japan’s fiscal deficit is one of the largest in the world.

To get out of this situation, it will be necessary to become specific about benefits and burdens and the choices that are available and to discuss this as a choice put to citizens.

The second issue is the relationship with the economy. When the consumption tax was increased to 5% in 1997, social insurance premiums were raised at the same time. This was also a period that experienced a global financial crisis. It is argued that this tax increase triggered Japan’s so-called lost two decades.

I do not agree with this view, based on a sober examination of economic indicators (GDP). Demand accelerated in January–March 1997 and then fell off in reaction in the April–June quarter. GDP, however, grew year on year in the July–September quarter. We can conclude from this that the subsequent recession was more the result of the financial crisis than the increase of the consumption tax.

When the consumption tax was raised to 8% in April 2014, the attendant acceleration and falloff of demand caused economic turmoil, and it took longer than expected for the economy to return to normal. While GDP contracted 7.3% in reaction in the April–June quarter, it was largely flat in the July–September quarter, which was followed by positive growth as the impact of the tax hike gradually dissipated.

Given the effect of consumption tax hikes on Japan’s economy, evening out economic fluctuations, such as the upsurge and falloff of demand, will be extremely important. The point is to increase the freedom of retailers in setting prices. Such measures are being taken in the current increase of the consumption tax.

Increasing the Consumption Tax in Small Steps

An approach that should be taken going forward is to raise the consumption tax in small steps. Consideration should be given to raising the tax over several years, in steps of 1 point or 0.5 point. An increase of 1 percentage point is about the same as the potential growth rate of the economy, and its economic impact will be small.

Raising the consumption tax in small steps had not been regarded as realistic since it would be time consuming for businesses. This choice, however, is no longer unrealistic, with cash registers being upgraded to deal with a reduced tax rate for food and beverages and with the adoption of an invoice system for claiming tax credits on taxable purchases.

The revision of the pension system in fiscal 2005 resulted in the social insurance premium being adjusted over a period of 13 years. The premium rate of the employees’ pension was increased by 0.354 point each year from October 2005 to reach 18.30% in fiscal 2017. The monthly premium of the national pension was increased ¥280 each year from April 2005 to ¥16,900 in fiscal 2017. It will be important to learn from this process.

Finally, the introduction of the consumption tax as a basic tax and the subsequent increase of the tax rate has made tax revenues more stable. Repeated reductions of the income tax over the same period, however, has weakened income redistribution in Japan. The ratio of income tax revenues to national income in Japan is about 60% of that of other advanced economies.

The weakening of income redistribution is a problem that needs addressing to promote the healthy formation of opinions by the middle classes. Tax reform to strengthen redistribution will be necessary, such as replacing income deductions with tax credits. Another important point that should not be overlooked is to integrate the design of tax reform with social security on the expenditure side

(Originally published in Japanese on May 16, 2019. Banner photo: Nikai Toshihiro, secretary-general of the Liberal Democratic Party, responding at an April 22, 2019, press conference to comments on the consumption tax made by Hagiuda Kōichi, executive acting secretary-general of the LDP, at left. Nikai expressed his displeasure at Hagiuda suggesting the possibility of dissolving the House of Representatives to seek the confidence of voters on the postponement of the consumption tax hike. © Jiji.)

Abe Shinzō consumption tax social security consumption tax hike