Japan Diversifies its Foreign-Policy Portfolio: Charting Its Own Course in an Age of Uncertainty

Politics- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Japanese foreign policy these days presents a number of different faces to the world, some of them difficult to reconcile with one another. Prime Minister Abe Shinzō plays up his personal bonds with US President Donald Trump and stresses the continued primacy of the Japan-US alliance. Yet his government is also at pains to portray itself as a key defender of the rules-based liberal international economic order that the Trump administration is accused of undermining. The Abe cabinet has also diverged from Washington in its China policy, doing business with Beijing at a time when the United States has all but washed its hands of “constructive engagement.” Yet where South Korea is concerned, it has adopted a Trumpian unilateralism, pronouncing its neighbor “untrustworthy” and removing it from its whitelist of favored trading partners. How can we account for such inconsistency?

Faced with the increasingly adversarial nature of US-China relations, Tokyo has begun acting more independently on individual foreign-policy matters, even while taking care to avoid any head-on collision with Washington on the big issues. But this balance between allegiance and independence is by nature unstable since it is linked to two variables that may change in the coming years: the personal relationship between the Japanese and American heads of state on the one hand and the international situation (dominated by the US-China relationship) on the other. The outcome of the 2020 US presidential election and the trajectory of US-China relations could have a major impact on the evolution of Japanese foreign policy going forward.

A Drifting Partnership

JUS trade negotiations have finally begun to bear fruit, but it was not so long ago that Trump was bashing Japan over the bilateral trade imapan-balance and the costs of the Japan-US security arrangements. Such attacks receded into the background as America’s dispute with China took center stage, and these days, the Japan-US partnership appears to be on a firm footing. But that impression is based largely on carefully staged displays of friendship and solidarity between Abe and Trump. If we examine the two countries’ policies more closely, we see cracks behind the facade.

For example, although both governments tout “a free and open Indo-Pacific,” their visions of the FOIP differ significantly: Washington seems intent on building a security coalition to contain China militarily, while Tokyo envisions the development of a more comprehensive regional order predicated on the rule of law, the market economy, and rules-based trade. Where the last is concerned, Tokyo remains committed to building and strengthening multilateral trade frameworks. It worked successfully for the conclusion of the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (although it would much prefer the Trans-Pacific Partnership pursued by US President Barack Obama and abandoned by Trump), as well as the Japan-EU Economic Partnership Agreement, and it has shown a willingness to tackle reform of the World Trade Organization as well. The same cannot be said of the Trump administration.

Of course, the Japanese government has long maintained a certain degree of independence from Washington in the areas of economic diplomacy and relations with its Asian neighbors. But now Japan has staked out a position quite distinct from Washington’s on the fundamental issue of economic multilateralism—albeit without going so far as to provoke the Trump administration’s ire.

Engaging with Russia and China

Tokyo has also been asserting its independence with respect to Russia and China. Where the former is concerned, one need only consider how many times Abe has met with President Vladimir Putin in recent months, at a time when both the United States and the European Union—incensed by Russian cyberattacks, interference in the Ukraine, and so forth—are giving Putin and his government the cold shoulder. Of course, one could argue that Abe is only doing what he feels he must do to advance negotiations on the disputed Northern Territories. But the bottom line is that Japan is going its own way in the pursuit of economic cooperation with Russia.

Tokyo is showing similar signs of independence in its China policy. While Washington has effectively turned its back on constructive engagement, Tokyo has adopted a posture of “conditional engagement,” most notably in respect to Beijing’s Belt and Road initiative. This has led to the exchange of 52 memorandums on cooperation in third-country markets (though no concrete progress thus far). Nor has Tokyo capitulated to Washington’s hard line on Chinese 5G technology. Moreover, in the midst of a US-China tariff war ignited by the Trump administration, Japan has upheld its basic policy of working to lower tariffs and ultimately create a mega–free trade area including China via such frameworks as the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (encompassing ASEAN) and the trilateral Japan–China–Republic of Korea Free Trade Agreement.

Differences are also emerging in the realm of regional security. Of course, Japan and the United States are in basic agreement vis-à-vis the need to denuclearize the Korean Peninsula. But the Trump administration has adopted a more conciliatory attitude consistent with its interest in summit diplomacy with North Korean leader Kim Jong-un. The Abe cabinet (even while relaxing somewhat its conditions for a Tokyo-Pyongyang summit) has remained stern and unyielding in its language and conduct toward the North. As mentioned above, Tokyo has also been slow to embrace Washington’s geopolitical interpretation of a “free and open Indo-Pacific.”

Limits to Japan-China Détente

It would be wrong, however, to conclude from the foregoing that Japan and China have mended fences in any lasting or meaningful way. Abe and Chinese President Xi Jinping are certainly talking to one another more than they did previously, but the basic source of tension between the two countries has not changed. China’s military presence in the East China Sea has not diminished in the least, and the Coast Guard is more active than ever in the area.

What we are seeing is a short-term shift in priorities. Faced with serious economic challenges, exacerbated by a trade war with the United States, Beijing can scarcely afford a total breakdown in relations with Japan, the world’s third-largest economy. In this context, it has reached out to Tokyo in the belief that a temporary détente is in its own best interests. Tokyo, which is already struggling to steer a perilous course between China and the United States, sees no need to provoke another quarrel with Beijing at this time. And the fact is that Japan and China share an interest in building regional trade frameworks, such as the RCEP and the Japan–China–ROK FTA, to prevent the spread of high tariffs that could hurt their own export-led economies.

In short, a number of factors, in addition to the trade conflict between the United States and China, are encouraging Beijing and Tokyo to put the best possible face on their relationship, at least for now. But this a temporary warming, not a permanent thaw. The territorial and security issues dividing the two countries are very real and unlikely to disappear anytime soon.

A Delicate Balance

Japanese foreign policy has always been a balancing act, but striking the right balance has become a more complex and challenging task than ever before. The Trump administration has introduced a new element of instability and unpredictability into Washington’s foreign policy. Along with the rest of East Asia, Japan is concerned about the economic impact of the trade conflict between the United States and China, given the latter’s vital role in the regional economy. But it is also concerned about China’s military expansion and the possible spread of a Sino-centric order predicated on the values of Xi Jinping’s Communist Party. Like other countries in Asia, Japan has close economic ties with China, but it is in a better position than most to withstand pressure from Beijing. All these factors—not to mention the dynamics of domestic politics and public opinion—must be taken into account when charting a course for Japanese foreign policy in today’s uncertain environment.

With such considerations in mind, the Abe cabinet is asserting its independence from Washington on specific issues, even while maintaining its basic commitment to the Japan-US alliance and its focus on good rapport between Abe and Trump. Where China is concerned, this means responding to Beijing’s economic advances without forgetting that, on the security front, the two countries are fundamentally at odds. Accordingly, Tokyo is evaluating the merits of economic cooperation project by project, without going so far as to jump on the Belt and Road bandwagon. Its challenge is to portray itself to the world as a defender of the liberal international order, while cooperating with China regionally and avoiding any open rift with Trump’s America-first policies.

Japan is not the only country negotiating this kind of delicate balance. We see similar nuances in the foreign policies of Germany, Australia, and other countries that want to uphold the liberal international order while avoiding the economic consequences of a cold war with China. They have begun responding flexibly to specific foreign-policy issues in a manner reflecting their own priorities. They recognize that, in both the United States and China—but especially in the United States—the domestic political climate can change, and foreign policy can shift as a result. With such considerations in mind, Japan and other industrial democracies have adopted a case-by-case approach to relations with China and the United States, as they attempt to maneuver within certain limits, keeping a close eye on the situation as it unfolds. That has inevitably produced variable, multifaceted policies lacking in strict internal consistency.

This trend might be one sign of a global order in transition. Or, it may simply be a response to the Trump administration’s own unpredictable policies. It is really too soon to say. The answer will largely determine the direction of Japan’s independent foreign policy and the speed at which it develops in the years ahead.

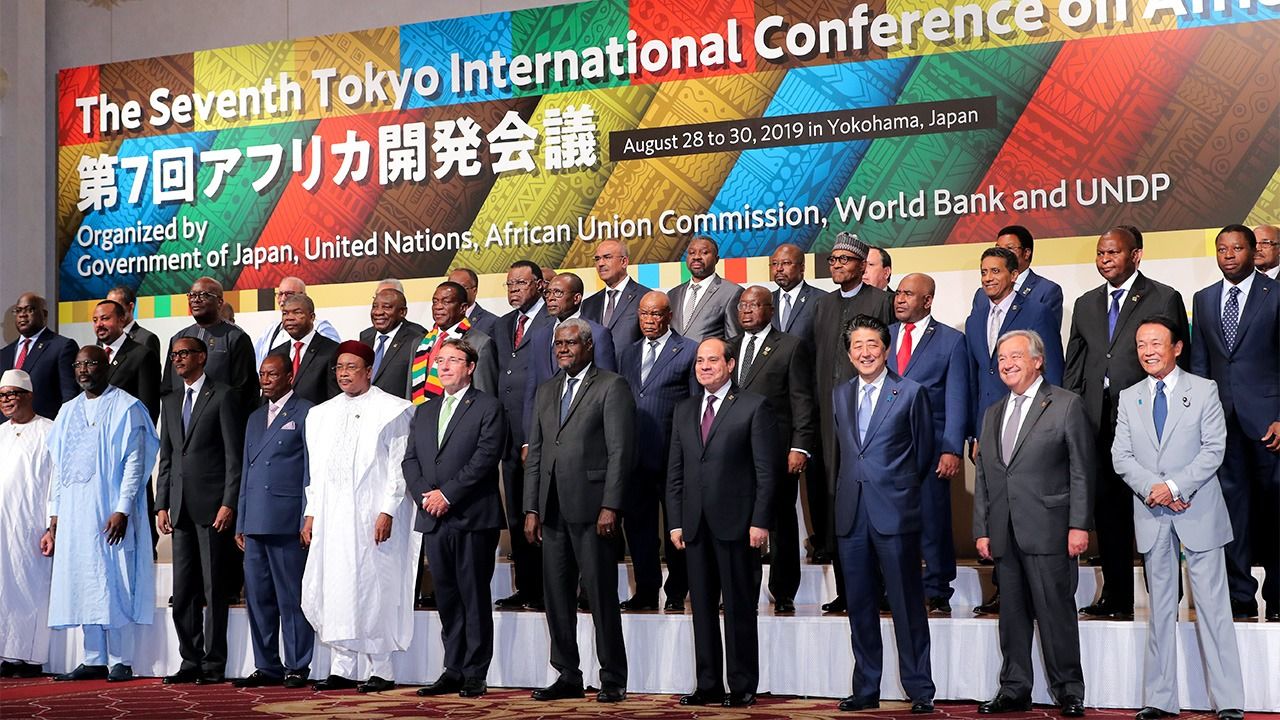

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Prime Minister Abe Shinzō, third from right, poses with African heads of state at the opening of the seventh Tokyo International Conference on African Development in Yokohama, August 29 , 2019. ©Jiji.)