Champions and Candidates: Japan and the Nobel Prize in Literature

Culture Books Arts- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Pairs of Rivals

Three Japanese-born authors have won the Nobel Prize in Literature since it was first awarded in 1901: Kawabata Yasunari in 1968, Ōe Kenzaburō in 1994, and Kazuo Ishiguro in 2017. Each is thought to have had a correspondingly strong Japanese rival. These were Tanizaki Jun’ichirō for Kawabata, Abe Kōbō for Ōe, and Murakami Haruki for Ishiguro. However, Tanizaki and Abe died while still considered prize contenders. Under the award’s rules, it cannot be made posthumously—in 1931 only, it was exceptionally bestowed on the recently deceased Swedish poet Erik Axel Karlfeldt.

As nominations and other aspects of the selection process remain under wraps for 50 years, I am merely speculating that Murakami was a candidate in 2017. Yet, if there was the idea of honoring a “Japanese” writer every two decades or so—Ōe won 26 years after Kawabata, and Ishiguro 23 years after Ōe—it would not surprise me if Ishiguro and Murakami were battling for this slot. The British bookmaker Ladbrokes has regularly positioned Murakami as a favorite to win, while he is also a more popular writer than Ishiguro.

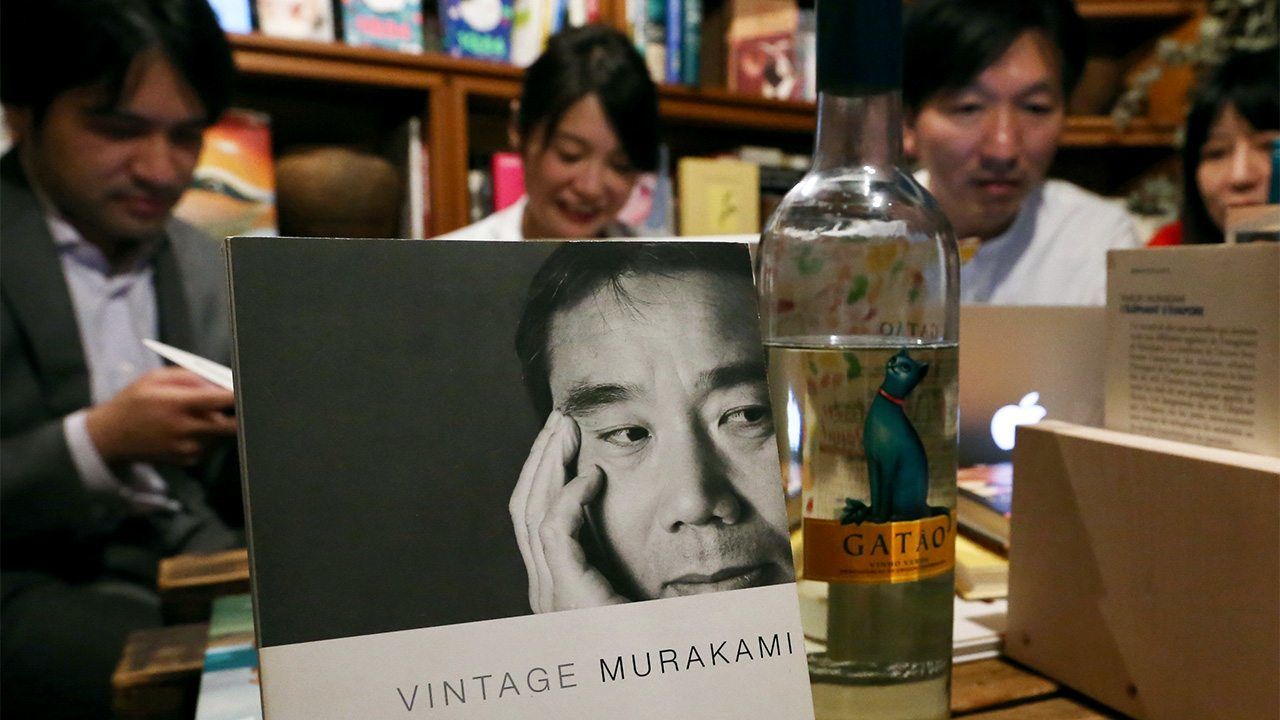

Murakami Frenzy

It was the same with Ōe, but in recent years a frenzy of speculation about Murakami as Nobel winner has descended on the Japanese media. In early October, before the official announcement, television stations, newspapers, and magazines frantically battle to interview people connected to Murakami, record their comments, and prepare columns and TV content. The man himself—difficult enough to secure for interview in normal times—is said to decamp overseas during this season of Nobel madness.

Yet, if Ishiguro is considered by the Swedish Academy as Japanese, Murakami will have to wait at least another decade before receiving the award. Based on the cycle to date, the next chance would be around the 2040s, when he would be very elderly, if still alive. And a younger generation of rivals like Tawada Yōko and Nakamura Fuminori is already on the rise.

A Translation Prize

Based on archives that have been made public, Japan has had four confirmed candidates who did not win the prize: Kagawa Toyohiko, Tanizaki Jun’ichirō, Nishiwaki Junzaburō, and Mishima Yukio. Although unconfirmed, Abe Kōbō, Inoue Yasushi, and Tsushima Yūko are strongly believed to have been later candidates. Others like Endō Shūsaku, Ibuse Masuji, Ōoka Shōhei, and Nakagami Kenji may well also have been nominated.

None of the selectors picked to date by the Swedish Academy have understood Japanese. Given that they have to read writers’ works before choosing who to give the prize to, those authors creating outside the main European languages like English, French, German, and Spanish are at a disadvantage. Japan’s candidates have either had an unusual number of works translated into European languages or have themselves written in languages other than Japanese.

Japan’s first Nobel literature candidate, Kagawa Toyohiko—nominated in 1947 and 1948—had his works translated into English at an early stage. As a Christian and social activist, he gave speeches in the West and knew many people connected to the church. His nomination was not really based on his reputation as a writer in Japan, and he is now a forgotten presence in the country’s literary history. Meanwhile, Nishiwaki Junzaburō wrote poetry in English as well as Japanese, and published an English-language collection.

Incidentally, Donald Keene had a fascinating story about Mishima’s nomination. A Danish author, who read Keene’s translation of Mishima’s Utage no ato (After the Banquet), a book set around a Tokyo gubernatorial election, told him that he had advised the selection committee that Mishima was “left-wing,” thereby wrecking his chances, and opening the door for Kawabata to become Japan’s first winner. Mishima was apparently gravely disappointed by this result.

The Nobel Prize in Literature could be described as a translation prize. Works in minor or non-European languages have to be translated for their authors to enter contention. Other than Kawabata and Ōe, winners writing in Asian and African languages are limited to Rabindranath Tagore (Bengali), S. Y. Agnon (Hebrew), Gao Xingjian (Chinese), Naguib Mahfouz (Arabic), Orhan Pamuk (Turkish), and Mo Yan (Chinese). The lack of translations from non-European languages has no doubt limited the number of winners.

Dylan Shock

In 2019, two awards will be made for literature. The Swedish Academy postponed its 2018 prize announcement for one year after scandals involving sexual assault and leaking of winners’ names. I do wonder, however, whether the brouhaha surrounding the choice of Bob Dylan as laureate in 2016 was also a factor. Traditionally, the prize has been given to writers of fiction, poetry, or plays, so the academy’s honoring of Dylan, a singer-songwriter, was a huge shock.

The decision won mixed reactions. While some praised the extension of the definition of literature—as in the case of the 2015 laureate, the Belarusian nonfiction writer Svetlana Alexievich—others blasted the deviation from traditional values. I myself was quite puzzled by the far-fetched invocation of Homer to justify the choice.

There were also different views on Dylan’s subsequent behavior. For some time after the announcement, the academy was unable to get in touch with him and he failed to attend the official award ceremony. There must have been friction and arguments during the selection process, decided by a majority vote. The prize felt like it had returned to its unequivocally literary roots the next year with Ishiguro, but perhaps the selection committee members were still feeling the aftereffects of the Dylan controversy. I think that from 2019 on, there will be a continued emphasis on serious literature, rather than fresh attempts at broadening the award’s scope.

Expanding Beyond the West

As Asia and Africa have been underrepresented to date, we might expect to see future winners from places like South Korea, Southeast Asia, Iran, and Iraq,

South Korea has been waiting expectantly for a winner for quite some time, but the poet Ko Un, long considered its most promising candidate, looks unlikely to be recognized, due to his age and a recent sexual harassment scandal. Novelist Hwang Sok-yong is another potential Korean laureate. Other possible Asian winners include Bao Ninh of Vietnam and the Taiwanese sisters Chu T’ien-wen and Chu T’ien-hsin.

It is clear from considering the history of the literature prize that selectors have eschewed those with extreme political views, as well as writers of popular fiction. This latter point is why Graham Greene was rejected, despite receiving nominations.

When Winston Churchill was awarded the prize, the academy came under heavy criticism, and is said to have later refused to accept major politicians as candidates. This is thought to have been why French writer André Malraux was not honored—he was minister of cultural affairs under President Charles de Gaulle. If Mario Vargas Llosa had not been defeated by Alberto Fujimori in the 1990 Peruvian general election, he may not have gone on to win the literature prize in 2010.

Through the prize, the Swedish Academy is likely to continue its pursuit of the ideal of world literature, based on universal humanism. While cases where it seems to have missed its target are not uncommon, I feel it will push forward to recognize more writers with linguistic backgrounds outside of Western Europe.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Murakami Haruki fans gather in Tokyo for the announcement of the winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature on October 13, 2016. © Jiji.)