Japan: a Paradise for Anthropomorphic Characters

Culture Anime Manga Entertainment- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Flags as Samurai

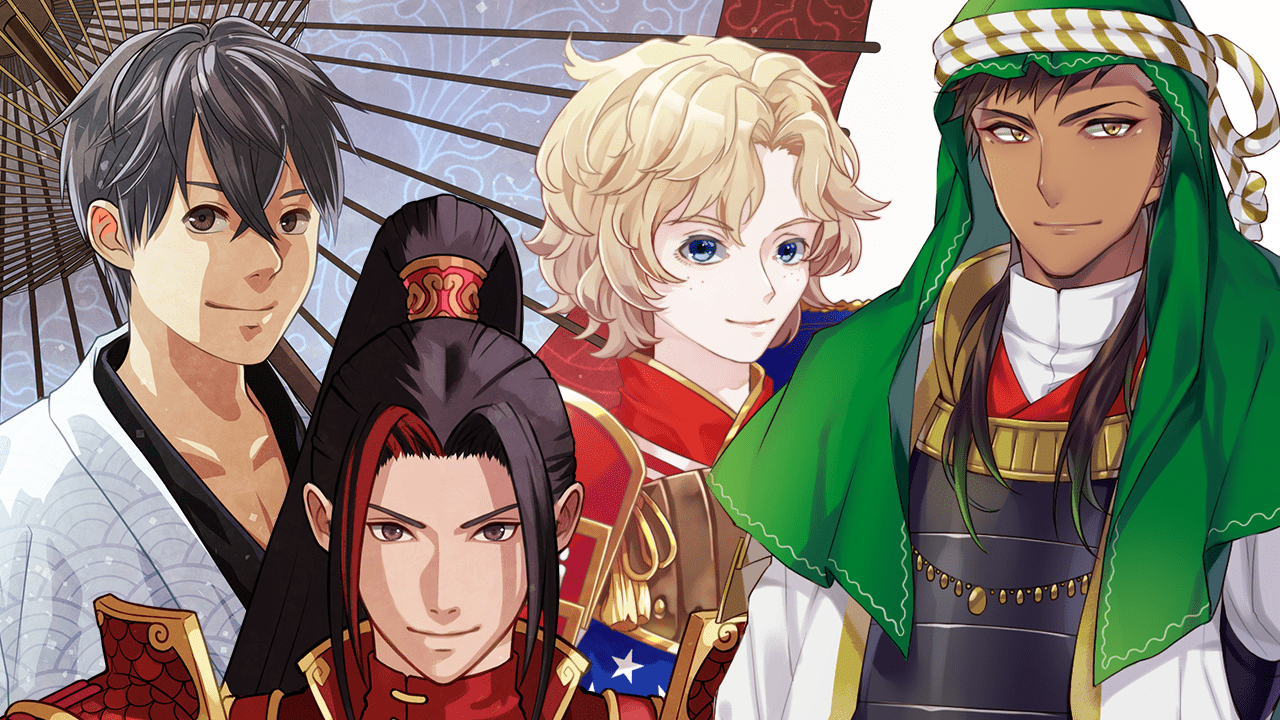

A Japanese website reimagining world flags as handsome young men is making a splash in the runup to the 2020 Summer Olympics in Tokyo. Through the characters, the site introduces the origins of the flags and the cultures of the different countries they represent.

The site depicts Japan’s flag as a strapping young samurai. As the obvious aim is to get people around the world interested in Japanese culture, any number of widely recognized cultural icons would do. However, the theme is apt, as Japan’s national teams for baseball and other sports are nicknamed “samurai” for their fighting spirit.

It is interesting that the creators chose to personify flags as good-looking men, considering the common reliance on images of beautiful young girls that appeal to male fans or even androgynous mascots. Japan’s knack for personifying objects as attractive people has gained recognition in East Asia, but I am curious how the rest of the world will receive the flag project. I am also fascinated to see whether it will catch on with men and older people.

From left: The personified flags of Japan, Spain, France, Russia, and Britain. (© WorldFlags)

Combining Motifs

Personification is everywhere in Japan today. It is part of branding campaigns for such disparate entities as railway stations, coffee shops, and computer languages. It is also a fundamental aspect of the mascots and other characters that are ubiquitous across Japanese culture.

Creators have learned to be resourceful and experiment with different motifs when making new characters. This can be seen particularly with Japan’s growing army of regional mascot. Designers will commonly start with a basic outline and then blend references to regional features like local dishes, tourist spots, wildlife, or famous historical figures.

For instance, the character for Okegawa, next door to where I live in Saitama Prefecture, sports the town’s official flower, a safflower, on its head and wears the garb of a traveler from the Edo period (1603–1868) to invoke the town’s history as a post station on the old Nakasendō highway. However, the various characteristics mascots convey are not always so concrete. Characters representing political or corporate entities, for instance, are known to communicate abstract concepts like “peace” or “the future.”

Oke-chan, the mascot for Okegawa, Saitama Prefecture.

The character for Tennōzu Isle Station on the Tokyo Monorail provides another example. The area combines the traditional Japanese place name “Tennōzu” with the English word “isle,” and the station’s mascot is imagined as someone with mixed Japanese and Western roots.

Creative Amateurs

Personification emerged as a form of metaphor and has been applied for educational and satirical purposes since time out of mind. In modern societies around the world, it remains popular in children’s education, is a standard in satire and parody, and is much used in advertising. While these trends continue, in Japan it has come to be used in an increasingly wide range of fields.

Since the 1990s, groups of mostly female fans at events like Comic Market have cast their favorite characters from popular works in completely new situations, creating original content with fresh scenarios.

In the late 1980s, self-published magazines reimagined characters from well-known children series like Anpanman and Doraemon as handsome protagonists in “boys’ love” stories, manga that depict romantic relationships between male characters. Such works established anime parody as a subgenre and can be traced back further to the late 1970s, when readers submitted stylized versions of famous characters to fan club publications and anime and manga magazines.

The arrival of the Internet and the spread of computers and smartphones have hugely changed the reach, and subsequently appeal, of amateur works. Derivative material posted on personal websites, blogs, and social media now reach a wide audience, unlike with the small fan communities of earlier decades.

Anyone wanting to create a character with broad appeal is wise to avoid obscure elements that play to only a small slice of society, but instead pick a motif that people can easily relate to. In the 2000s, this approach lead to a host of characters based on mundane items—blackboards, railway stations, and sushi toppings, just to name a few—public bodies like prefectures, temples and shrines, and even political parties.

As the personification phenomenon picked up steam, the initial emphasis was on creating characters that were truly original—cockroaches reimagined as beautiful girls and the personification of Japan’s war-renouncing Article 9 of the Constitution won a lot of interest. However, personification has mushroomed to the point that nowadays almost anything can become reimagined as a character, and quality has come to be more in demand than novelty.

Personification in the Mainstream

Since the early 1990s, a seemingly endless parade of fluffy promotional mascots, known colloquially as yuru-kyara, have appeared, representing a staggering array of bodies and organizations like local governments, law enforcement, corporations, universities, and even regional business associations.

These mascots have generally taken inspiration from children’s entertainment, being cute and cuddly so as to ensure broad appeal. However, some have mimicked the scantily clad female characters most frequently associated with otaku culture—although often at the risk of becoming the focus of public ire for objectifying women.

Japan’s Self-Defense Forces has readily adopted such subculture elements to create a vast cast of characters representing everything from the different SDF branches to regional bases. In particular, the SDF has viewed the approach as a potentially effective means of recruiting. For instance, the regional headquarters in Yamaguchi Prefecture uses three female characters—air, land, and sea forces—clad in outfits more resembling the mobile suits of the Gundam anime series than a modern armed force. It is arguable whether this is personification or not, but the effect is much the same.

The three mechanized characters represent the three branches of the Self-Defense Forces.

An Evolving Tradition

Personification in Japan has been around since the middle ages, as can be seen notably in the famous anthropomorphic creatures of Chōjū giga, a set of ancient scrolls depicting different frolicking animals, and the fanciful portrayals of the various chapters of The Tale of Genji produced over the centuries. Even today, there remains a strong element of playfulness, helping personification become accepted by people of all ages.

This traditional expression has found new manifestation in subculture events like Comiket and has developed even further through shared spaces on the Internet. I will be watching with interest to see where it goes next.

(Originally published in Japanese on November 5, 2019. Banner image: Handsome samurai representing the flags of (from left) Japan, China, the United States, and the United Arab Emirates. © WorldFlags.)