China’s Sharp Power Comes to the Fore: The Values Gap Grows Clearer in the Academic Sphere

Politics- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Political Involvement Brings an End to Months of Detention

On September 8, 2019, the Chinese authorities detained Hokkaidō University Professor Iwatani Nobu at a Beijing hotel. Professor Iwatani’s work on early modern and modern Chinese history has taken him frequently to libraries and archives in Taiwan, the United States, and of course China, and he has developed a reputation for meticulous research. This incident was widely reported in the Japanese media when it finally came to light on October 18; while Japan’s domestic press treated the story as a detention on suspicion of espionage, a Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson would only state that Iwatani was being held for breaking Chinese law.

Once the situation became known, a broad range of Japanese academic and research societies—including key bodies like the Association of Scholars Advocating Renewal of the Japan-China Relationship, the Japan Association for Modern China Studies, the Japan Association for Asian Studies, the Japan Institute for International Affairs, and the Nakasone Peace Institute—began issuing statements on and formal objections to Iwatani’s detention. Major dailies including the Asahi Shimbun carried columns by researchers criticizing China’s actions, while the Nikkei printed an editorial lamenting the state of affairs.

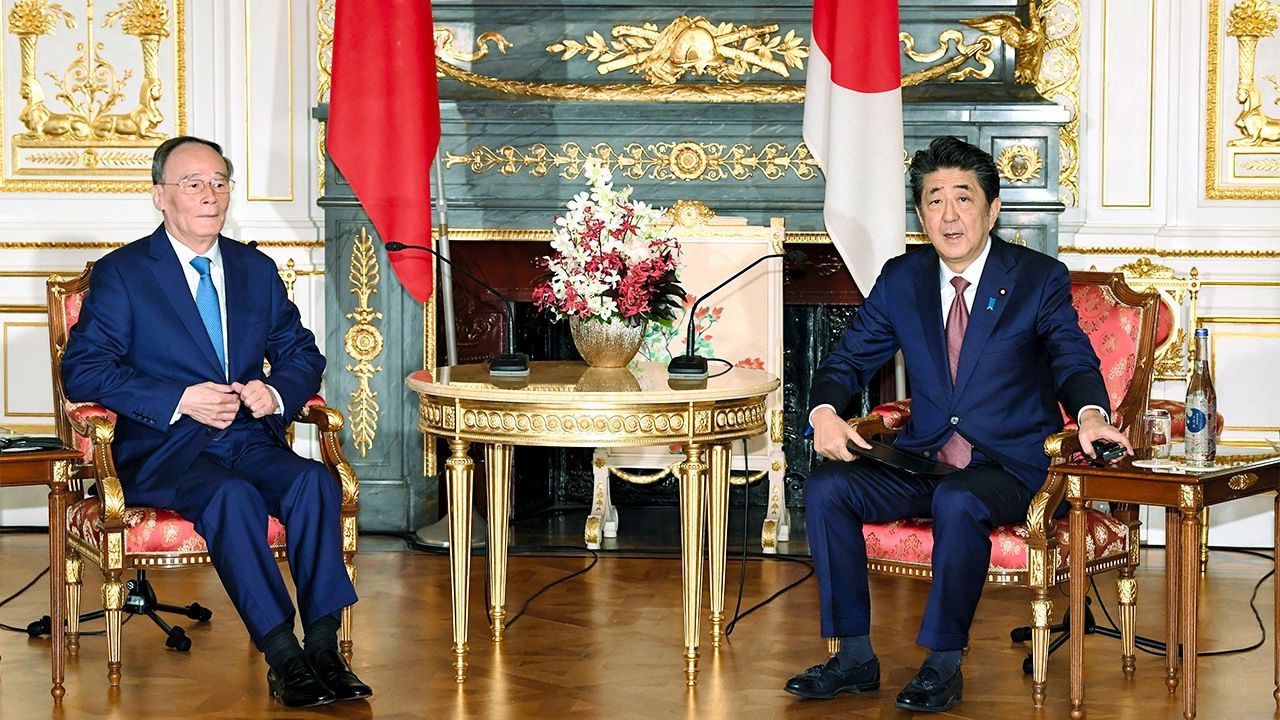

Before Iwatani’s detention came to public light, the Japanese government was conveying its concern and alarm at the case to the Chinese side. Toward the end of September, Minister for Foreign Affairs Motegi Toshimitsu expressed the Japanese position to Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi. This position was reiterated by Prime Minister Abe Shinzō to Vice President Wang Qishan, who visited Tokyo to attend Emperor Naruhito’s October 22 enthronement ceremony, and to Premier Li Keqiang on November 3 at the East Asia Summit in Bangkok. In these meetings the Japanese side evidently stressed the need to resolve this case swiftly for the sake of a successful state visit to Japan next spring by President Xi Jinping.

On November 15, after more than two months in Chinese custody, Professor Iwatani was released. It seems likely that Prime Minister Abe’s talks with Li Keqiang were a decisive factor—the Japanese leader, in turn, was probably moved to elevate the priority of the Iwatani case by the pressure of public opinion, if not by the strong hopes and requests voiced by Chief Cabinet Secretary Suga Yoshihide and others close to the prime minister. Details like these aside, though, the facts are that just five months or so ahead of Xi’s visit to Japan, formal requests from the prime minister and other members of Japan’s government and a growing mood of Japanese opposition to the continued detention of Iwatani helped to secure his release. This step was not one that the Chinese authorities took lightly, as is evident from the fact that it has received only spotty coverage in China’s state-controlled media, and what coverage there is consists mainly of quotes from the Chinese Foreign Ministry. This may mean that the authorities are fearful of being accused of “weakness” by the Chinese public for releasing the Japanese citizen.

The Sino-Japanese “Values Gap” Is Wide as Ever

Iwatani’s release (technically, he is out on bail at this point) took place on November 15. On that day, a Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson gave an explanation of the events in the case up to that point. However, this explanation served only to deepen worries about the future course of exchanges between China and Japan and to shed fresh light on the gulf existing between the sets of values and systems of order held by the Chinese and the Japanese.

First is the Chinese claim that on September 8, when agents from the Ministry of State Security searched Iwatani’s hotel room, they recovered materials having to do with state secrets. Their investigation showed that the professor was in possession of state secrets, and that he admitted to having collected a considerable amount of such secret materials in the past. Based on this discovery of sensitive materials and the suspect’s admission of his past activities, say the Chinese, there was reason to suspect him of violating China’s criminal and anti-espionage laws.

However, Iwatani was in China at the invitation of the Institute of Modern History in the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, and was staying in lodgings arranged for him by the institute. This raises specific questions about how the authorities came to receive reports that the Japanese researcher was in possession of materials requiring investigation. Speaking more generally, though, it raises warning flags for all researchers who might be considering a visit to China—particularly if their area of research is China itself.

Second is the question of what exactly constitutes “state secrets.” Historians gather materials relating to their topics of study all the time; those studying China will naturally do so in that nation. This places them in possession of physical materials or digital data related to their work. If the Chinese authorities are able to declare that this information is “state secrets,” with no clearly defined standards for this, it is a problem of considerable concern to researchers. Even if the authorities do have some clear set of definitions of the scope of secret material, if that scope is not made clear to researchers as well, they will need to tread very carefully indeed while working within China’s borders.

Third is the Chinese legal system itself. Once a person is detained by the authorities, it is difficult to secure the services of a lawyer to defend oneself against whatever charges are brought. And while visits by officers from the foreign detainee’s embassy are allowed on a certain schedule, that schedule does not guarantee frequent consular visits by any means. These issues point to the gap that exists between the law as it is implemented in China and in developed nations. And even if the detainee is released, there are many points of that detention that he or she will not be allowed to discuss publicly—a restriction that I expect will be in place for Iwatani as well. This makes it difficult to build up a body of knowledge regarding legal precedents in China.

Tracked on the Streets and Attacked Online

Thankfully, Professor Iwatani has been released, but this will not clear away the worry still felt by Japanese academics and Japan’s society as a whole. The scope of application of China’s anti-espionage law remains as murky as ever. To date 14 Japanese citizens have been held by the Chinese authorities, who went on to press charges against 9 of them. And those charges are also vague in many cases.

The situation is also concerning for Chinese citizens. At around the time of Iwatani’s detention, it became clear that a Chinese national doing research on international political history at the Hokkaidō University of Education had not been in contact with his colleagues for several months. There have been other cases of Chinese citizens who teach at universities in Japan being detained upon their return to China. Many of them with positions at national or private universities in Japan have been held for brief periods, and in one notable case, an instructor at a Japanese private school was detained for around six months. While their stories have yet to receive press coverage, I have heard of other Chinese researchers who can no longer be reached, perhaps because they are being detained.

Meanwhile, there has been a ceaseless stream of reports of detentions by China of researchers and businesspeople carrying other passports, including from the United States, Canada, Australia, and Taiwan. One cause of this is said to be the increasingly tough treatment of Chinese researchers in the United States, set against the backdrop of the trade and economic friction between the two powers. But this is not the sole cause of these cases. The rising numbers of foreigners, and Chinese nationals with foreign work experience, who are detained by the Chinese authorities have their roots in China’s own moves to strengthen its grip on every aspect of Chinese society. In seeking to supervise and control all people in China, the Beijing government has begin applying its approaches more broadly to foreign nationals in the country, as well as Chinese citizens with some connection to the outside world.

It is only natural, of course, for foreigners to obey Chinese law while in China. But given the differences between China’s legal frameworks and interpretations and those seen elsewhere around the world, it must also be said that in the past the Chinese authorities have not been so stringent in applying them to foreigners as soon as they entered the country. This is something that we are now seeing change. This is an issue very much related to China’s ongoing effacing of the “one country, two systems” approach that has held sway in Hong Kong since its reversion to Chinese administration in 1997.

Nor is this change something that appeared out of the blue in the form of Professor Iwatani’s detainment. China studies specialists who travel to that country for their research have in recent years found themselves under constant observation as they go about their activities there, and if they speak out on some issue in a way that opposes the official Chinese position, they have at times come under cyber attack or subjected to some other form of reprisal. However, even while they felt threatened by actions like these, most researchers remained confident that China would not cross the line into physically detaining visitors to the country. Many people must have greeted the news of Iwatani’s arrest with the realization that it could happen to them as well, and this widespread understanding is what drove participation in the widespread protests against his detention.

The Dangerously Flexible Definition of “State Secrets”

This problem is not one that only affects university faculty and researchers. It is unclear what “state secrets” may include, and the Chinese authorities have tremendous leeway in interpreting their definition to suit each case. Charges related to possession of sensitive information could easily be brought against journalists, NGO workers, government officials, and businesspeople as well as academics. You may be in possession of scientific data, or geological survey findings; you may just have purchased some volumes at an antique book shop. There is still the chance that China could accuse you of carrying sensitive information and accuse you of espionage. This does not, of course, mean that anyone and everyone is in danger when traveling in China, but still, unease that has once been sown in this manner is hard to clear away. Nor am I saying that people should hold off from engaging with China for the time being. Indeed, I believe that the time has now come for us to recognize this stance as an impediment to greater exchange with the Chinese people and to work to do away with it.

In the realm of the global economy, China positions itself as a defender of “free and open” international economic and trade frameworks. Its precise definitions of “free and open” may depart somewhat from those held by the nations of the West, but on the surface, at least, the Chinese are not opposed to the existing order. When it comes to international politics, though, things are different. China is not in opposition to the United Nations, but it has plenty of stark criticism for global security frameworks with the United States at their center, freedom of academic inquiry and speech, and freedom of thought and belief, among other norms cherished by the West. The gulf separating the Chinese position from that of Western nations grows wider all the time.

The Iwatani case has dealt a serious blow to the field of China studies in Japan, and the lack of clarity surrounding the facts of the case and the standards guiding application of the law have only made its impact heavier. Chinese researchers specializing in Japan remain able to come to the country and freely pursue their data collection and other research activities here, but it seems likely to become harder for Japan’s China specialists to do the same when going the other direction. Another possibility is that Japanese researchers who want to go to China will need to ensure that their writings and statements align with the positions of the Chinese government and Communist Party of China.

This Chinese method of extending its influence to the outside world through systemic asymmetries is emblematic of the country’s “sharp power.” It is easy for China to go out and make its impact felt in developed nations; the opposite is not true. The United States is seeking to construct “walls” of sorts that will prevent this from happening, but the effectiveness of these measures has yet to be seen.

What is the likelihood that China will continue triggering problems like this between itself and other nations and regions, including the developed world? If it sticks to this path, it could find itself standing out more starkly in opposition to other nations around the globe, particularly those developed ones whose systems are most asymmetric in comparison to China’s. Unless these issues are addressed appropriately, the Japan-China relationship could see similar incidents take place in the future in business and other fields, not just in academia. This would shake the very foundation of Sino-Japanese ties.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Chinese Vice President Wang Qishan, at left, pays a visit to Japanese Prime Minister Abe Shinzō on October 23, 2019, the day after attending Emperor Naruhito’s enthronement ceremony in Tokyo. © Jiji.)